In 1952, the Mattachine sent candidates a survey that was exposed in the local press.

In 1952, the Mattachine sent candidates a survey that was exposed in the local press.

Who responded?

by David Hughes

Posted January 4, 2018

A Triad: Part III

1952 was a watershed year for the Mattachine. The organization had begun its engagement with the larger community by standing in solidarity with Mexican Americans who, like homosexuals, were targets of the Los Angeles Police Department. With the arrest of its cofounder Dale Jennings in March of that year the Mattachine had a test case of its own to rally ’round, but in that effort the group turned inward rather than outward. I examine this dynamic in the first of three articles, “Harry Hay Meets His Match.” I also look at the remarkable woman Hay met along the way.

The gamble to back Jennings paid off. His superb legal representation—bankrolled by Mattachine fundraising—resulted in a hung jury, allowing the organization to capitalize on an impossible dream: an admittedly homosexual man beating a charge of lewd vagrancy. My article, “Blown Cover: The Arrest of Dale Jennings,” reviews some of the particulars of the case, including the identity of his arresting officers. I also examine LAPD’s liberal employment of the lewd vagrancy allegation as well as its use of a tactic known as the “third degree” and brutalization in general.

In the fall of 1952, emboldened by Jennings’s success in court, the Mattachine once again turned its gaze outward, this time to civic leaders and local candidates for office. The vehicle of outreach was a brief survey known to have been completed by only three or four respondents, but when it came to the attention of a local newspaper columnist, the concerns he voiced about the Mattachine turned out to reflect those already in the minds of its members, as discussed in the present article.

The following is adapted from my work-in-progress with the working title The Feeble Strength of One: Bob Hull, Chuck Rowland, Maxey, Marx and the Mattachine. Because its length likely would prevent its eventual publication as-is, I offer it here.

Prologue

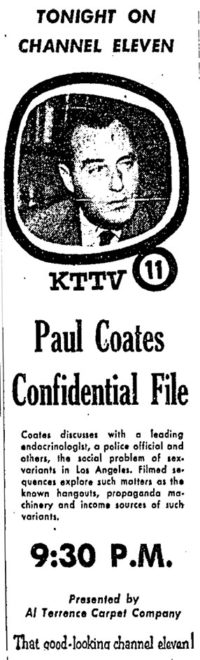

Students of LGBTQ history likely are aware of the impact of a column written by Paul Coates for the Los Angeles Mirror in March of 1953.

It would have been most newspaper readers’ introduction to the Mattachine Foundation, which had scored a victory nine months prior—not reported by the press—when Mattachine cofounder Dale Jennings beat a vagrancy-lewd conduct rap (which I discuss here). As a “first,” the article was considered quite valuable to the leadership of the Mattachine, which reprinted it by the thousands.

The catalyst for Coates’s column was a survey the Foundation sent to local candidates in the fall of 1952 and winter of 1953 asking for responses to such loaded questions as “Do you favor the continuance of the quota assignments currently issued to members of the Vice Squad Detail?”

Coates in his column followed up with questions of his own about the organization behind the Mattachine name, questions that caused a Mattachine discussion-group regular, Marilyn “Boopsie” Rieger, to ask her questions of the group. The Coates column is seen as the catalyst for calls of transparency within the organization, although already there had been signs of discontent.

What may not have been discussed heretofore regarding the matter of the Mattachine questionnaire is exactly who responded to it.

This past August, I worked with researcher Mark Sawchuk in obtaining Mattachine records from the GLBT Historical Society. I mentioned to Mark in passing that there was some confusion about who had completed the survey, and he told me that he actually had run across the respondents’ forms—three of them—and he forwarded them to me. I already had drafted a profile of the man Harry Hay had identified as the sole respondent. Historian James Sears ID’d another as the “only candidate to complete the questionnaire.” But Mark sent a third. And he sent what turned out to be two versions of the questionnaire’s cover letter as well as a second version of the survey itself. I am grateful for his initiative.

What follows is in two parts. Queer Questionnaire discusses the versions of the Mattachine survey that caught Coates’s eye; Coates Column looks at the newspaper columnist’s famous write-up as well as the Mattachine’s response to it, both amongst the leadership and the rank and file.

Queer Questionnaire

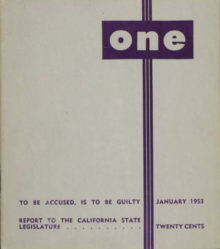

At the same time as the genesis of ONE magazine, in October and November of 1952, the Mattachine tried a new tactic to interface with the press consisting of a questionnaire sent to candidates for office prior to the November 4 presidential and state election and the upcoming municipal election on April 7, 1953.[1]Katz (1976, 416) ascribes the mailing of the questionnaire to the “fall of 1952.” Hay said the letter was sent in “Oct & Nov 52,” according to D’Emilio’s interview notes, and that the … Continue reading

“The Foundation’s first, brave attempt to assault the media was in the form of a letter which we had printed on our brave new letterhead,” Mattachine cofounder Chuck Rowland recalled in late 1976.[2]Two of the three versions of the letters available to me (including FBI transcriptions) are addressed to candidates for office; the third is addressed “Dear Friend” (Cutler 1956, 16). The … Continue reading

(We pooled our meagre funds to pay for it.) The letter was sent to various clergymen and members of the city council and to certain candidates for public office. The message announced our interest in pursuing the study of ‘social and sexual deviation’ and asked the recipients to respond with their reactions to our lofty scientific objectives. The letter caused a minor fuss in some quarters […] but was something less than the bombshell we expected it to be.

It would not be until nearly the ides of March 1953 that the letter would be discussed in the local press. Rowland recalled: “It did elicit one very significant response, however, from Dr. Wallace […] de Ortega Maxey of the First Universalist Church who became one of our staunchest advocates—and suffered rather dismal consequences as a result.”[3]This and above quotes from Rowland to D’Emilio, 11 Dec 1976 (D’Emilio 1970s). Despite those consequences, Rev. Maxey continued his involvement with the Mattachine long after its founders had fallen away.

Three Surveys

Three questionnaires are known to have been sent out by the Mattachine Foundation: a general survey for which only the cover letter remains, and two candidate surveys.

Dear Friend

Only one survey’s cover letter is dated—December 1, 1952—leading off with a “Dear Friend” salutation and containing much detail about the Foundation’s endeavors: a Discussion Group Committee (directing gatherings “in existence for several years”—in reality less than two), the Citizens’ Committee to Outlaw Entrapment (dealing with “a corrupt Police Department”), and a Publications Committee (mailing all municipal judges a copy of Cory’s The Homosexual in America). This survey, since the cover letter does not mention the upcoming election, is likely the one to which Rev. Maxey responded, as noted by Chuck Rowland above. (Cutler 1956, 16–17)

Request for Information

The two undated municipal election mailings consist of two parts: a cover letter and a multiple-question survey. The first letter’s subject is “Request for Information” addressed to “Candidates for Mayor, City Council and Board of Supervisors.”

It begins by calling the Mattachine Foundation “a non-partisan service council devoted to the social objective of integrating with the purposes and requirements of the community the enormous potential of valuable civic contributiveness and concern of such ill-understood social minorities as the homosexuals.” (Perhaps unintentionally, this signaled interest in bisexuals, transsexuals, and more.)

The letter points out that Dr. Alfred Kinsey had appeared before a committee of the state legislature in 1951,[4]This committee, called simply the Interim Committee in the Mattachine letter, is identified by Paul Coates, as discussed below, as the State Interim Committee on Sex Deviation, but the actual name is … Continue reading providing statistics that allowed for an estimate that “there are at least 150,000 such persons in the Los Angeles area alone.”[5]The 150,000 statistic in the Mattachine cover letter: “If only a conservative percentage of Dr. Alfred Kinsey’s testimony […] is conceded, there are at least 150,000 such persons […].” How … Continue reading While the Mattachine maintains neutrality, “it welcomes any opportunity to disseminate as many variant and/or opposing partisan opinions as can be engendered.” (Lucas 1997 1:1)

The letter’s second paragraph draws upon the Dale Jennings entrapment experience.

There is a growing body of evidence to indicate that the Los Angeles Police are assigned to deliberate practices, with regard to the Homosexual Minority, which in Federal, State, and Municipal Courts, other than those of the Los Angeles Area, are considered explicitly unlawful. Quota assignments, decoys detailed specifically to entrap, invasions of privacy by fraudulent means, searches-seizures-and [sic] arrests without due process of law, arraignments handled in coercive and unconstitutional procedures,—even though they are harassments aimed at a Minority who can be counted on to hide these civil infractions at all costs,—such illegalities can be characterized as corrosive factors not only in police administration, but as factors conducive to further corruptions within the general administration as well. (Lucas 1997 1:1)

The seven questions in the survey follow up on the charges of the above paragraph, asking the respondents if they favor the quota assignments, decoys, confiscation of address books, arrests without warrant, and improper arraignments, and to provide their reasoning. The last two questions ask what policies the candidate would propose regarding the above matters, and “If you are unfamiliar with any of the items indicated above, upon being elected what might you be expected to do in these matters?”

The survey closes with a notice that could have given the respondents pause: “The Foundation wishes to assure you that any opinions which you present will be published exactly as they were queried above and as you answered them.” If any municipal candidates responded, their surveys did not find their way into archives.[6]The cover letter and questionnaire are transcribed in FBI 1953, 8–9. Only the cover letter is collected in Lucas 1997 1:1.

A Third Survey

The second municipal election mailing is addressed to “Candidates of the Board of Education,” its cover letter’s second paragraph being tailored to these contenders.

A consensus of the opinions of most psychological experts on this matter indicates that the social manifestations of this minorial [sic] deviancy begin to appear in young people between the ages of 12 and 15. A new opinion, now being advanced in several quarters, holds that the anti-social neuroses, generally associated with this category of deviance, appear as the result of community harassment and social oppression upon the deviance…….rather than the neuroses being the cause of the deviance. In such regard, the counselor activities programs employed in most Junior High School and Senior High School operations assume an almost pontifical disregard for the integral social health of minority-majority understanding. When the early pre-pubic manifestations of sexual deviance appear, usually unbeknownst to the victim himself, they are glossed over, singled out for group ridicule, or tacitly negated by mechanically attempting to fit the square peg of deviation into the round hole of the traditional “team-work” formula. In this regard, the public school system may claim a high percentage of responsibility of the social and civic tragedy of this misfit minority.

The accompanying three questions allowed a lot of leeway for the respondents.

- Would you support the inclusion of a non-partisan psycho-medical presentation of homosexuality in the required Hygiene Courses of Los Angeles’s Senior High Schools?

- Would you favor a parent-teacher, and/or a minister-teacher consultation program for the purposes of emotional health and social guidance of those young people who begin to manifest subconscious aspects of social deviance?

- Would you favor that the Board of Education require that applicants for Senior High School Counselling positions be adequately trained to advise and guide young people manifesting such problems, using the most current techniques and knowledge? (Lucas 1997 1:1)

Three school board candidates were not put off by the assurance to publish respondents’ opinions “exactly […] as you answer.” They were civil libertarian attorney Leo Gallagher, liberal attorney David Ravin, and Matthias W. Merrill, a Mormon Republican and self-described teacher, administrator, and businessman.[7]I’m grateful to Mark Sawchuk for making me aware of these three completed questionnaires in Lucas 1997 1:1. Despite these completed questionnaires, historian James Sears (2006, 246, 252 n12) writes that “oddball heterosexual attorney” David Ravin “was the only candidate to complete the questionnaire distributed by the Foundation,” and Harry Hay wrote three decades after the fact that “Leo Gallagher was the one candidate who responded favorably,”[8]Hay to Jim Kepner, 20 Jul 1983 (Hay Papers 12:9). ignoring the fact that Ravin wrote on his questionnaire of being “thoroughly sympathetic with your approach.” Only Merrill wrote of a “problem” and “unfortunate situation” to be “successfully solved,” implying that resolution could involve conversion rather than compassion. The three respondents represented a cross-section of political views that deserves fleshing out—from lefty lawyer to liberal community volunteer to Mormon bishop.

Leo Gallagher: Fellow Traveler

Leo Gallagher seems to have been the sort of fellow actually to have brushed elbows with Harry Hay, so it’s no surprise that Hay singled him out when recalling the Mattachine questionnaire respondents.

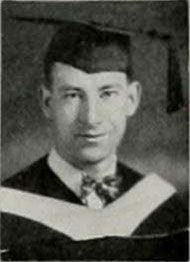

Born in Kansas in 1887, raised in Texas, and graduating high school in Buffalo, New York, Gallagher received a law degree from Yale in 1910. He then became a seminarian, receiving a doctorate in 1915 from a school in Innsbruck, Austria. The next year he worked in the agricultural fields of California before receiving military training and joining the army in World War I.

After the war he was admitted to the Bars of Texas and California, practicing law and teaching in Los Angeles. In the mid 1920s during the San Pedro dock strikes he attended IWW meetings and hooked up with the International Labor Defense, a forerunner of the Civil Rights Congress. Later he would become a charter member of the National Lawyers Guild.[9]Gallagher’s biographical details, unverified by me, are from Biography, Register of the Leo Gallagher Papers, 1922–1963, MSS 012, Southern California Library for Social Studies and Research, … Continue reading

In 1933, Gallagher ran for municipal court in Los Angeles and succeeded in getting activist Tom Mooney a new trial of his conviction for the notorious 1916 San Francisco Preparedness Day parade bombing, with the lawyer claiming his client was the victim of a “capitalistic frame-up.”[10]“Eighteen More File Petitions,” Los Angeles Times, 24 Feb 1933, A1; “New Mooney Trial on Old Indictment,” Boston Globe, 26 Mar 1933, A1. Tom Mooney Labor School was the original name of the … Continue reading Also in 1933, given his presumed proficiency in the German language, Gallagher attended (as observer and defender) the trial of the event “that boosted Hitler to power”[11]“Rites Set Today for Attorney Leo Gallagher,” Los Angeles Times, 01 Oct 1963, 24.—the Reichstag fire, whose sole German defendant Ernst Torgler declared his innocence; as a Reichstag deputy Torgler would have been immune from prosecution but the communist party he led was outlawed by the Nazis.[12]“Torgler Affirms Innocence in Fire,” New York Times, 26 Sep 1933, 1. In 1934, Gallagher ran for California Supreme Court Justice.[13]“Many Seek Woolsacks,” Los Angeles Times, 26 Aug 1934, 15. He was a “perennial” candidate for superior court, including in 1938, eventually running that same year on the Communist Party ticket for California Secretary of State.[14]“Fifty-seven in Judge Race,” Los Angeles Times, 28 May 1938, A3; “Leo Gallagher to Run on Communist Ticket,” Los Angeles Times, 27 Jun 1938, 5. In 1939, Gallagher was de facto head of a commission investigating the death of a student at a boys’ school in Whittier, but had to renounce his own findings, having been accused of “stern” questioning of the boys that “intimidated them and prevented them from telling the whole truth to the committee.”[15]“Inquisitor Repudiates Boy’s Suicide Findings,” Los Angeles Times, 23 Aug 1940, 30; “Report Calls for Shake-up at Whittier,” Los Angeles Times, 08 Dec 1940, 1. In fact, Gallagher could be quite confrontational, once being ejected by a judge twice on the same day.[16]See, for instance, “Judge Ejects Leo Gallagher,” Los Angeles Times, 18 Dec 1937, 5; “Court Warns Defense Counsel in Water-Front Murder Trial,” Los Angeles Times, 13 Mar 1941, A3.

In 1940, Gallagher successfully argued against a ban of Communists from the California ballot.[17]“Red Ballot Ban Dissolved,” Los Angeles Times, 04 Oct 1940, A [sic]. The day Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066, Gallagher (representing the ACLU) appeared at a meeting of “[m]ore than 1500 Nisei and their elders […] as leaders of Los Angeles’ Japanese colony launched the organization that they hope can successfully fight the threatened evacuation of Japanese-Americans [sic], as well as all enemy aliens, from the Pacific Coast defense areas for the duration of the war.”[18]“Nisei Launch Organization to Fight Coast Evacuation,” Los Angeles Times, 20 Feb 1942,10.

Gallagher ran for the Los Angeles school board in 1949, asking voters to support him as a Communist, but the local party demurred, stating he “is not a member of the Communist Party; does not represent the program of the Communist Party, and the Communist Party in no way endorses his candidacy.”[19]“Apathy Over School Board Race Causing Apprehension,” Los Angeles Times, 24 Mar 1949, 4. Indeed, he appears never to have joined the party.[20]Biography, Register of the Leo Gallagher Papers, 1922–1963. Gallagher last ran for office in 1954 in the Democratic primary for U.S. Senate against Sam Yorty (Los Angeles’ future mayor), who won but was defeated in the general election.[21]“Registrar Hite Lists Names on Primary Ballot,” Los Angeles Times, 07 Apr 1954, 2; “Election Returns,” Los Angeles Times, 03 Nov 1954, 1.

Gallagher responded to the Mattachine candidates questionnaire. As Harry Hay later recalled it,

Leo, in Spring of 1953, was running for the Board of Education[22]Gallagher was running for Office 4 of the Los Angeles school board, as noted on his questionnaire. and when our questionnaire […] suggested that Homosexual relations be included in the viable patterns of sexual behavior presented to the High School Hygiene classes, Leo responded by saying he thought that he and all members of the School Board should learn more about the subject. I believe we had sent him a few pieces of our material before Paul Coates’ blasts in his syndicated column focussed all our attentions elsewhere.[23]Hay to Jim Kepner, 20 Jul 1983 (Hay Papers 12:9). Coates wasn’t syndicated nationally until he moved to the Los Angeles Times in 1962. See “Paul Coates, Noted Columnist and TV Personality, … Continue reading

Gallagher’s completed questionnaire does not reflect Hay’s recollection regarding school board members themselves learning more about “the subject.” Rather, Gallagher replied, “Persons, holding themselves out as counsellors to High School students should have adequate training to effectively discharge their duties.” He also wrote, “The findings of science should, of course, be used wherever practical.” (Lucas 1997 1:1)

David Ravin: Devil’s Advocate?

Attorney David Ravin did not elaborate his affirmative responses to the Mattachine survey’s three questions[24]Ravin was running for Office 2 of the Los Angeles school board. See “123 Candidates File for Municipal Offices,” Los Angeles Times, 01 Feb 1953, B1. except to say that he thoroughly sympathized with the Mattachine approach and had been contacted already about the organization by Donald Webster Cory, author of The Homosexual in America (Lucas 1997 1:1). Ravin also had connections within the African-American community of Los Angeles, being profiled during the school board campaign by the Los Angeles Sentinel, although he told a group of teachers that urged him to run “he considered himself a representative of the entire citizenry, not any special group or particular element within the community,” as the Sentinel wrote.

Ravin graduated from St. John’s University in New York City, where he passed the bar in 1930, doing so in Los Angeles a decade later. He served as a civilian in World War II as a lawyer for the National War Labor Board, which was charged just weeks after Pearl Harbor with reining in a labor force that had conducted at least 2,361 strikes in 1941 involving 2,389,685 workers.[25]“Labor’s ’41 Record and Outlook in ’42,” New York Times, 02 Jan 1942, 39. Ravin taught insurance law at a local law school as well as labor relations at USC. He was a member of the Urban League and the Masons; worked with settlement houses and the YMCA; and was a panel member of the American National Arbitration Association. Even though he was father only to a girl, he volunteered with the Boys Club.[26]Ravin’s biographical details, unverified by me, are taken from “Attorney Ravin Lists Election Qualifications,” Los Angeles Sentinel, 19 Feb 1953, A10.

Ravin, a registered Democrat, subscribed to ONE magazine of his own accord after returning the Mattachine questionnaire.[27]Ravin’s party registration is listed in Index to Register of Voters, Los Angeles County, California, Los Angeles Precinct No. 1866, 1952, and Los Angeles Precinct No. 4009, 1954. Mention of … Continue reading He eventually was retained by the Mattachine Society that summer of 1953, an association that began with a referral by Wallace Maxey following the FBI’s contact of David Finn, chair of the Legislative Committee in San Francisco.

Although Ravin previously had defended homosexuals in court he was not willing to do so for the Society; nevertheless he was retained for three months beginning July 1. Ravin urged caution on the one hand, counseling against publishing a “Your Rights in Case of Arrest” circular as appearing too pinko and that meetings of Mattachine chapters ran the risk of facing conspiracy charges. On the other hand he suggested that the organization would obtain no status with heterosexuals until it declared itself publicly by incorporating, a move he admitted would lead to targeting.

If Ravin was the Mattachine’s legal counsel, he also was devil’s advocate to the point that the Society’s Legal Chapter secretary found Ravin “totally and specifically ignorant of the homosexual problem” and refused to discuss the subject further with the lawyer. Ravin’s approach to a Mattachine strategy had convinced the Society’s secretary Boopsie Rieger otherwise, however, and it was she who originally had proposed that he tell the Coordinating Council what he’d told her in private. Ravin’s presentation at the council’s August 28 meeting was so provocative, and its transcript in Rieger’s minutes so generous to Ravin, that the legal chapter called for nearly a dozen emendations at the next meeting, September 11. The Legal Chapter had every reason to be riled; Ravin essentially had called for its dissolution, feeling that its existence, if made known, would intimidate and anger a heterosexual society that felt safeguarded by laws that single out homosexuals. To repeal such laws would smack of special rights in the minds of heterosexuals and thus only education could change this misconception.

If the Legal Chapter was challenged by Ravin, so was the Research Committee. “Mr Ravin stated that all research on the subject of homosexuality was useless,” the Legal Chapter noted in one of its many emendations. Ravin’s advice for the Mattachine was to focus on what mattered. Although Ravin had met Dr. Evelyn Hooker at the July 20, 1953 Coordinating Council meeting, he could not have foreseen the impact of her experiment whose nonclinical subjects she would meet ten days later. “This revolutionary study provided empirical evidence that normal homosexuals existed” wrote American Psychologist in April 1992. Ravin felt that lofty legal efforts, let alone revolution, were counterproductive. “Mr. Ravin thought we should be honest with ourselves in admitting what we really are after,” read the August 28, 1953 minutes, reduced to: “the elimination of Vice Squad in ‘gay bars’ so that it would be easier to make acquaintances.”

But Ravin carried this further, insulting the sensibilities of an organization that had enjoyed a remarkable victory just a year before in successfully fighting the entrapment of Dale Jennings. Ravin “pointed out that heterosexuals are ‘entraped’ [sic] as well as homosexuals. As for handling of these cases by lawyers, he failed to see what a lawyer could do for a person who has violated the law.” The chair of the Legal Chapter countered that “it was morally wrong for the Vice Squad to try to entice people in gay bars and felt that we should fight this. He felt that if the Vice Squad was ‘planted’ in gay bars, then they should also be ‘planted’ in bars where heterosexuals congregate, for the same purpose.”[28]This homo-versus-hetero discriminatory practice by vice officers was raised at City Council in Denver in 1973, mentioned briefly at the end of my previous article in this triad. Secretary Boopsie Rieger closed the discussion by addressing the Legal Chapter members.

I never even knew of the situation of the Vice Squad and police tactics until I became aware of it through the fellows I have met here. I still believe it is a situation created by yourselves and that you are attacking the problem from the wrong end. You are only going to bring ill-will [sic] from Society by trying to change laws rather than try to educate society to the fact that you are human beings with the same feelings as anyone else.

Ravin’s regard for research and rules notwithstanding, Coordinating Council chair Ken Burns gave the attorney the benefit of the doubt. “I would not like to see us take an attorney who will be entirely sympathetic to us and not give us an overall picture of the situation […],” Burns told his colleagues.

Discussion of Ravin’s retainer and its toll on the Society’s treasury dragged on until well after the retainer had expired September 30, being tabled at the October 16 meeting for reconsideration after the Mattachine convention in November. The Ravin matter crept into a special legal policy meeting convened by Burns the next week and again was tabled. Nevertheless at that meeting matters were addressed that Ravin had raised—matters Rieger had recognized as pertinent to Society concerns. At issue was “what policy the Society is to follow…whether we shall embark upon a program of legal assistance, or a policy of public relations [and] education to build up the name Mattachine,” as summarized by the Southern Area Council chair.[29]Details regarding Ravin’s relationship with the Mattachine Society are taken from available Coordinating Council minutes. Ravin appeared at the 20 Jul and 28 Aug 1953 meetings and was the topic of … Continue reading It was David Ravin, the “oddball heterosexual attorney” (as described by James Sears), who in part led the Mattachine to consider its priorities.

Matthias Merrill: “Something MUST be done immediately”

The third known respondent to the Mattachine candidates questionnaire was Matthias Wood Merrill,[30]Merrill was running for Office 2 of the Los Angeles school board, as noted on his questionnaire. grandson of Marriner Wood Merrill who had been appointed a Latter Day Saints Bishop of the Ward of Richmond, Utah by Brigham Young in 1861. A century later Matthias himself would be Bishop of the church’s Matthews Ward, South Los Angeles Stake.

Born in Richmond in 1905, he graduated from Brigham Young College in 1926, attended the University of Utah in 1927, and graduated with a B.S. from USC in 1930.[31]A Ruth Viola Merrill is listed in Matthias’s graduating class (1930 edition of El Rodeo, USC’s yearbook, p. 72), but this is not his sister. Ruth Merrill, his his next oldest sibling, … Continue reading Merrill taught high school in Litchfield Park, Arizona until 1931, obtaining his master’s in Public School Administration from USC in 1932.

A world traveler, Merrill and his wife Zelda (Boden) involved themselves with Milton R. Hunter, a Mormon seminary instructor with whom they journeyed to Latin America to study “archaeological ruins and their relation to the book of Mormon.”[32]Quoted from “News of the Church: Elder Milton R. Hunter Dies,” Ensign, Aug 1975. Biographical details of Merrill and his family, unverified by me, are taken from the section Matthias Wood Merrill … Continue reading Prior to his school board candidacy, in the Los Angeles area Merrill taught at adult and secondary schools, was a school principal, and worked in the dental-medical supply field wherein he developed his own business.

Unless Merrill held a sympathy for homosexuals that diverged from LDS orthodoxy, his responses to the Mattachine questionnaire can be read in light of his Mormon background. According to Wikipedia, the first public mention of homosexuality by an LDS church leader took place just about the time of the circulation of the Mattachine questionnaires.[33]Homosexuality and The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, accessed 30 Oct 2017. It was an address delivered on October 2, 1952 by J. Reuben Clark Jr., president of the LDS General Relief Society for which Matthias Merrill’s mother Rebecca Hendricks Merrill had been a teacher for forty years prior to her death in 1943.[34]Matthias’s father Alma had a polygamist marriage with Matthias’s mother Rebecca as well as her older sister Esmerilda. In his address Clark, on the topic of “Home, and the Building of Home Life,” advised parental vigilance in the face of modern cultural perils: newspaper ads (“sexy”), music (“I do not know how far above the tom-tom of the jungle it is”), and dance crazes (“You know the names that some of your choice dances had when they were first introduced” and “some of it came out of the voodoo huts”).

According to Clark, chastity itself was under attack by many influences: “the schoolroom, the press, authors, poets, artists, dramatists, musicians—all, consciously or unconsciously, are adding fuel to this flame of sexuality that is sweeping over the world.” College teachers were instructing their students “that the sex urge is like hunger and thirst and is to be satisfied at their wills,” said Clark. “He who teaches this depraved doctrine is acting as an emissary of Satan” in concert with “the person who teaches the non-sinfulness of self-pollution” or “who teaches or condones the crimes for which Sodom and Gomorrah were destroyed—we have coined a softer name for them than came from old” (just as popular dances had been “rechristened,” as Clark put it) thus “we now speak of homosexuality, which, it is tragic to say, is found among both sexes.” And Clark cited the burgeoning homintern: “Not without foundation is the contention of some that the homosexuals are today exercising great influence in shaping our art, literature, music, and drama.” Following his warning to mothers to exert their (limited) power in the home, “which is your duty to build” and to preserve children “from the second greatest of all sins, unchastity,” Clark quoted Matthias Merrill’s father’s namesake, the prophet Alma, speaking to his own son who had strayed (“his words, not mine,” Clark clarified):

Know ye not, my son, that these things are an abomination in the sight of the Lord; yea, most abominable above all sins save it be the shedding of innocent blood or denying the Holy Ghost? (Alma 39:3–5)

Clark appeared to end his address observing the opportunity to forgive the transgressor, but he hedged by discussing both the repentant and unrepentant—in equivocal terms. In the end it was up to the moms, “that you may mark the betrayer long before he strikes and so frustrate him; that you may sense, even before your loved one is aware, that Satan is slyly whispering waywardness into the innocent ear so that you may drown that whispering with the voice of counsel dictated by love and wisdom.”[35]All quotations are from “Home, and the Building of Home Life,” Relief Society Magazine, Vol. 39 (Dec 1952), 790–795.

With this sentiment, if not these words, in mind, Merrill, a registered Republican,[36]Index to Register of Voters, Los Angeles County, California, Los Angeles Precinct No. 211, 1952 and 1954. replied in the affirmative to the three questions of the Mattachine survey—as did the other two respondents, but in more detail.

No problem can be successfully solved unless we under stand [sic] it. I personally feel that it should be studied earlier that [sic] the Senior High School. Ground work in the Junior High school could be laid by the Physical Education Dept. if handles [sic] correctly.

All groups such as Doctors, ministers, parents, teachers, administrators, psychologists, etc. should combing [sic] their knowledge and know-how to study and help solve this unfortunate situation. Something MUST be done immediately.

Every concievable [sic] course of study in psychology, social mal-adjustment, human physicology [sic], anatomy, etc. should be studied. It would be well to get men with Doctors [sic] Degrees in Psychology to head up these Dept. [sic] if possible. In my opinion this is a MUST in our Los Angeles School Program. If elected I shall push this program to the best of my ability. (Lucas 1997 1:1)

But since homosexuality was by definition unchastity and as such, according to Mormon doctrine, the second greatest of all sins, Merrill hardly would have been sympathetic to the Mattachine’s stated devotion “to the social objective of integrating with the purpose and requirements of our community the enormous potential of valuable civic contributiveness and concern of such ill-understood social minorities as the Homosexuals” (Lucas 1997 1:1). Such collaboration would be, in the words of Reuben Clark, “condon[ing] the crimes for which Sodom and Gomorrah were destroyed.”

In the End

Not surprisingly, incumbents won the board of education seats in the election on April 7, 1953. Merrill (8,315) and Ravin (7,522) came in seventh and ninth, respectively, in the second-office race, losing to Edith Stafford (232,434). Gallagher (19,187) came in third in the fourth-office match losing to Hugh Willett (231,121).[37]“Complete Returns in City Primary,” Los Angeles Times, 09 Apr 1953, 2. An “SOS” (Save Our Schools) slate obtained less than half the votes of the frontrunners. “The contest between these two groups has pretty well shaped up on the basic question of Americanism in the schools of Los Angeles,” the Los Angeles Times wrote two days before the poll. The incumbents had been criticized for favoring loyalty oaths imposed on teachers and opposing UNESCO-issued textbooks and materials. “The SOS slate of candidates have [sic] been warmly endorsed, on the other hand by the Daily People’s World, Communist Party news and propaganda organ.”[38]“34 Seek Three School Board Posts Tuesday,” Los Angeles Times, 05 Apr 1953, B1.

In the end, there is no evidence that the Mattachine did any endorsing of its own based on responses to its questionnaire, nor did it publish responses. But the group did reprint the newspaper column that put the questionnaire in the spotlight.

Coates’ Column

At about the time of the circulation of its questionnaire to candidates for office, the Mattachine was facing challenges, as I write in my profile of Gerry Brissette. “Not only was there ‘pressure from below’ in the Mattachine, as Harry Hay told historian John D’Emilio in his own 1976 interview, there also was rancor within the leadership. Thus a Mattachine conference had been called for February” of 1953. I also write, “Traditionally the milestone in ‘pressure from below’ has been seen as discussion-group reaction to Los Angeles Mirror columnist Paul Coates’s 12 Mar 1953 report on the Mattachine,” which I outline below, “but the rumblings appear to have started earlier as indicated by the February conference,” discussed in my manuscript.

From the Los Angeles Mirror’s Paul V. Coates in his column “Well, Medium and RARE”:[39]“Well, Medium and RARE,” Los Angeles Mirror, 12 Mar 1953. All quotes below are from this column.

This is an election year.

Anything can happen. And yesterday, something did.

The already harassed and weary candidates for office were whacked with a broadside from a strange new pressure group.

An organization that claims to represent the homosexual voters of Los Angeles is vigorously shopping for campaign promises.

Political questionnaires have been sent to all candidates by the Mattachine Foundation, Inc., a group which pointedly hints it has the potential support of 150,000 to 200,000 homosexuals in this area.[40]Coates’s inflation of the Mattachine’s figure of 150,000 in its cover letter to 200,000 Los Angeles area homosexuals appears to be explained by 1) the Mattachine’s cover letter ascribing … Continue reading

That Coates characterizes the Mattachine questionnaire and cover letter(s) as a “broadside” and its authors as “strange” are indications of how extraordinary and audacious the survey was in the eyes of Coates’s audience, if not the columnist himself.[41]Nine months later Coates would sell his new Confidential File television weekly by saying he wanted to expose rackets of all kinds: “I’ll take people where they ordinarily couldn’t and … Continue reading Coates summarizes the Foundation questionnaire, which appears to have been the seven-question version sent to candidates for mayor et al. “The questionnaire asks candidates to take a stand on present police control of sexual deviates,” he writes, “and also the policies they would recommend regarding homosexuals,” which does not reflect the survey sent to school board contenders.

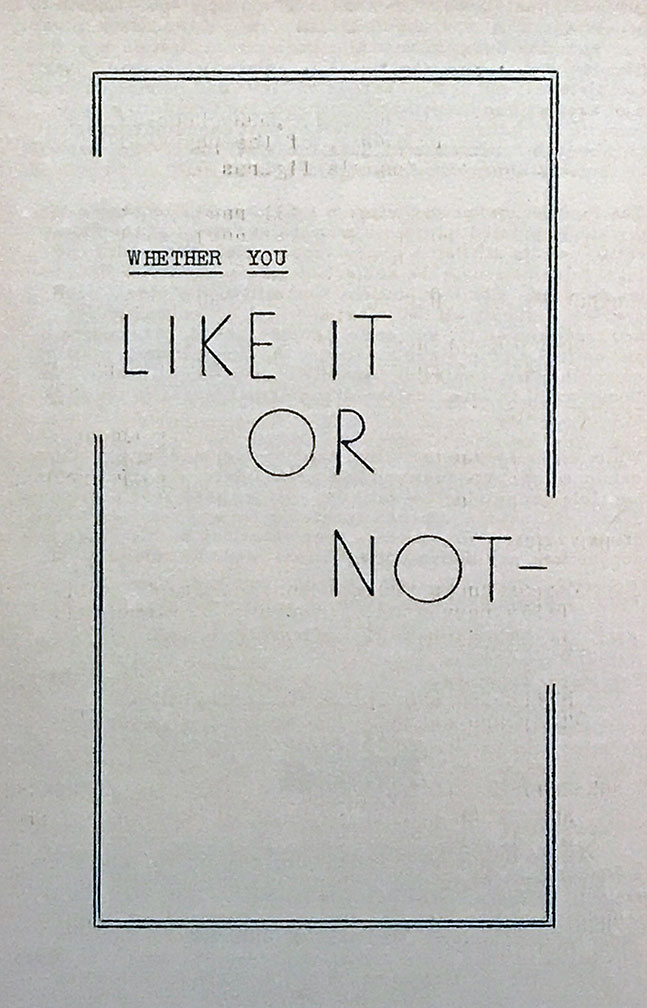

Coates also quotes from what he calls Foundation “literature” as well as an “accompanying letter.” At least one item of literature quoted is the four-page brochure titled “Whether You Like It or Not” as reproduced in Cutler (1956, 18–21).[42]For instance, Coates writes that the Mattachine looks forward to a time when homosexuals “will be accepted as useful citizens by an enlightened public,” quoted directly from the “Whether You … Continue reading The accompanying letter appears to have been neither of the two “Request for Information” letters nor the “Dear Friend” letter discussed above, because Coates uses the letter in his possession

- to quote the Foundation as calling homosexuals “one of the largest minorities” in the country—a phrase that does not appear in any of the three cover letters known to me,

- to quote the letter (and/or the Foundation; he uses “it”) as demanding new legislation to protect this minority from “police decoys, entrapment, confiscation of address books and phone numbers”—again a phrase not contained in those other three cover letters,[43]Coates could have been abstracting rather than quoting directly, since police decoys etc. are mentioned in the questionnaire sent to mayoral etc. candidates, but none of the cover letters or … Continue reading and

- to quote the listing of Romayne Cox as secretary-treasurer of Mattachine, Inc. [sic]—a name that appears on the “Dear Friend” letter but with neither of the above two quotes.

Continuing, Coates states that he contacted Mrs. Henry Hay (Harry Hay’s mother), to whom the Mattachine Foundation’s post office box was registered, who told him, “We started three years ago. Then we incorporated. Now we’re building groups in every community. There are many thousands of members.”

Coates questions this: “I checked the State Division of Corporations and the County Clerk’s offices. There is no record of a Mattachine Corporation.” Neither was he able to obtain from Margaret Hay nor “another member”[44]Coates refers to Margaret as Mrs. Henry Hay. “There were a few people who recognized my name as being one of the people mentioned in [the] column,” Harry told oral historian Tuchman (1987, 194), … Continue reading the whereabouts of Romayne Cox.[45]Cox was the sister of early Mattachine stalwart Konrad Stevens (Timmons 1990, 175). “That’s odd, too,” Coates writes. “The Mattachine Foundation survives by donations by interested parties. This elusive lady is the treasurer.”

Given that Coates twice cites the letter’s statistics—“the potential support of 150,000 to 200,000 homosexuals in the area” and “the figures of 150,000 to 200,000 [being] no idle guess” since they’d been taken from Alfred Kinsey and a state legislative committee[46]I discuss the computation of the 150,000 figure in this note.—he was quite bullish regarding the size of the Mattachine purse in Cox’s trust. “If I belonged to that club, I’d worry,” he warned. (In 1953, imagining himself as a homosexual evidently did not trouble the columnist, who the next year launched one of the first television interview shows to feature guests that “ran the gamut from prostitutes to high public officials.”[47]“Paul Coates, Noted Columnist and TV Personality, Dies at 47,” Los Angeles Times, 17 Nov 1968, H1.) After observing, “Homosexuals have been found to be bad security risks in our State Department,” for which there was no proof,[48]I discuss this in the section of my manuscript on Harry Hay and HUAC. Coates states the obvious—“They’re a scorned part of the community”—before sounding the alarm: “It’s not inconceivable that they might band together for their own protection. Eventually they might swing tremendous political power.” (A year later, this same message would appear in the pages of Confidential magazine.) “A well-trained subversive could move in and forge that power into a dangerous political weapon.” According to Coates homosexuality was a weapon wielded against national security yet had the potential to be wielded by homosexuals for political gain—a nuance not lost on the Mattachine.

A Balancing Act

As Stuart Timmons writes (1990, 174) about the Coates column, the journalist “cleverly straddled both sides of the issue.” On the one hand he asks, “Where is Romayne” and her Mattachine treasury, mentioning that Fred M. Snider, the attorney who drew up the Mattachine’s articles of incorporation, “was an unfriendly witness at the Un-American Activities Committee hearings.” But Coates concludes his column:

As Stuart Timmons writes (1990, 174) about the Coates column, the journalist “cleverly straddled both sides of the issue.” On the one hand he asks, “Where is Romayne” and her Mattachine treasury, mentioning that Fred M. Snider, the attorney who drew up the Mattachine’s articles of incorporation, “was an unfriendly witness at the Un-American Activities Committee hearings.” But Coates concludes his column:

To damn this organization, before its aims and directions are more clearly established, would be vicious and irresponsible.

Maybe the people who founded it are sincere. It will be interesting to see.

A year after the column appeared Coates devoted the May 2, 1954 installment of Confidential File, his new television show, to “sex-variants” including the Mattachine. If the ad for the program was slightly suggestive (“Filmed sequences explore…”), the program itself was praised by Daily Variety for its sensitivity.[49]”Confidential File,” Daily Variety, 04 May 1954, 9. “This was not riveting television,” writes Edward Alwood (1996, 31–32). It consisted in part of a Mattachine meeting with “twenty ordinary-looking men and women standing around a table in a homey living room, drinking coffee, and eating cookies.”[50]Alwood states that the segment aired on 25 Apr 1954, but the display ad appeared on May 2 for that day’s programming; the ad on 25 Apr claimed the segment would involve spiritualism. The San … Continue reading Two years after Coates’s column appeared, Jim Kepner wrote in ONE magazine, “Paul Coates, L.A. columnist seldom praised here, recently went to bat for sex offender and won his release from jail. Offender was 7-year-old boy accused of indecently touching girl. Thanks to Mr. Coats [sic] for spotlighting one case of fantastic official stupidity….”[51]“Tangents,” ONE magazine, April 1955, 16, reprinted in Kepner (1998, 62) but differently worded.

Timmons writes (1990, 175) that the Mattachine Foundation replied to Coates’s 1953 column, explaining “that the incorporation papers were filed but were in limbo” (the California Secretary of State recorded the filing on April 27[52]Business Entity Detail for The Mattachine Foundation, C0273698, accessed 22 May 2015.), “that their financial records were open for inspection, and that while Snider might be considered somewhat problematic, he was the only lawyer that would represent the controversial group.” The reply was not printed.[53]Timmons likely is informed by Tuchman (1987, 192), who quotes Harry Hay stating that in his telephone conversation with Coates, Hay said that since the Mattachine was “an unpopular cause” with … Continue reading

Bad Timing

The Mattachine reaction to Coates’s column was favorable, as Harry Hay told historian Jonathan Katz (1976, 417). “We all thought it was pretty good, and so we ran off twenty thousand copies to send out to our mailing list and to be distributed city- and statewide.” Concurring with this assessment a week after the column appeared were attendees of a Mattachine discussion group on March 20 (discussed further below), according to the meeting’s notes:

There were several members who were not quite as alarmed as the others seemed to be. These people felt that Mr. Coates [sic] article was very encouraging by refusing to damn this organization before its true aims and purposes are revealed…..that perhaps the people who founded it are sincere, and that we (the public) must wait and see.

It was also felt by these optimistic people that it was good to see the Mattachine’s name in print, and that this was probably the first time an organization dealing with the homosexual problem was known to the public. They felt it was a good thing that the public is now aware of the census of homosexuals in Los Angeles and that they are striving for better adjusted, well-oriented, socially productive lives.[54]Quoted from Notes of Discussion Group Meeting held Friday evening, March 20, 1953 (Lucas 1997 1:3).

But that same discussion group took note of Coates’s naming Fred Snider, the lawyer who was preparing the Mattachine’s articles of incorporation. “Wow! Whammo!” Harry Hay told Jonathan Katz (1987, 193). “We’d forgotten what the detail about Fred Snider’s being unfriendly to the House Un-American Activities Committee would do to the middle-class Gays in Mattachine.”

Bear in mind that, apart from any distribution of Coates’s column by the Mattachine, the column as published had only a local reach, despite claims to the contrary. In Tuchman (1987, 193) Hay recalls Coates’s column being nationally syndicated; likewise Hurewitz (2007, 263) writes that Coates was “a syndicated Los Angeles Daily Mirror columnist.” Coates wasn’t syndicated nationally until he moved to the Los Angeles Times in 1962; had he been—a decade earlier—, the exposure received by the Mattachine would have been greatly magnified.[55]See “Paul Coates, Noted Columnist and TV Personality, Dies at 47.”

Nevertheless, the timing of Mattachine’s reprint couldn’t have been worse. Eleven days after the column appeared in the Mirror, HUAC launched its Investigation of Communist Activities in the Los Angeles Area, with fifty public appearances in late March and early April.[56]The hearings are published in Parts 1 through 4 of the Los Angeles Investigations, which took place on 23–28 Mar, 30–31 Mar, and 7–8 Apr 1953. Executive (non-public) sessions also were held … Continue reading

Two weeks after the Coates column appeared, Chuck Rowland wrote a Northern California newcomer, Gerry Brissette, on March 29.

There has been a very considerable, delayed reaction to the Coates article. Some people are demanding the Foundation issue a “never have been, are not, never could be Communists . . . overthrow . . . force and violence.”[57]Rowland to Gerard G. Brissette, 29 Mar 1953 (Mattachine 2008 1:9).

Rowland, as the Mattachine discussion group committees coordinator,[58]Rowland’s title is given in Rowland to Brissette, 07 Mar 1953 (Mattachine 2008 1:9). would have been privy to groups’ discourse around the Coates column, such as one cited by historian John D’Emilio, who writes (1983, 76), “One Los Angeles discussion group,” on March 20 in the University Park neighborhood near USC, “appealed to the foundation’s directors to ‘make themselves known’ and bring an end to ‘subterfuge’.”[59]D’Emilio’s source is “Notes of Discussion Group Meeting” on that date. I am grateful to Mark Sawchuk for obtaining this (Lucas 1997 1:3). Continuing in his March 29 letter, Rowland says, “The Laguna group has become very recalcitrant. Some of them want a loyalty oath as a condition of membership.” Marilyn “Boopsie” Rieger, a guild councilor who was “an open lesbian at work” (Timmons 1990, 176), craved transparency in her March 23 letter to the Foundation following her attendance at that March 20 discussion group.

At our last discussion group meeting, the subject for discussion was the Paul Coates article […]. I feel that in order to continue working for a cause, I must have complete faith in the people behind the scenes, the people who set forth policies, principles, aims and purposes. Who are the people who make policy for the Mattachine Foundation, Inc.? Who is [sic] the Board of Directors? Who are Mrs. Henry Hay, Mrs. D. T. Campbell, and Romayne Cox? Why is there no record of a Mattachine Foundation, Inc with the Division of Corporations or the County Clerk’s office? […] I want to know what Mr. Snider’s political affiliations are […] What are the political affiliations of the Board of Directors? And finally, are the aims and purposes of the Foundation, which I have read and which I believe in, the true aims and purposes?[60]Rieger to Mattachine Foundation, 23 Mar 1953 (Mattachine 2008 1:8). I am grateful to Jeff Snapp for obtaining this. Sears (2006, 154) identifies Chuck Rowland as having “overseen” the discussion … Continue reading

Whereas Harry Hay (writing as his mother on Mattachine letterhead) responded enthusiastically to an earlier letter from Rieger (in which she had sent notes from a discussion group),[61]Hay to Rieger, 23 Feb 1953 (Lucas 1997 1:3). I am grateful to Mark Sawchuk for obtaining this. it took Hay a full three weeks—two days after the Mattachine’s first constitutional convention and only after being prodded by Chuck Rowland—to reply to Rieger’s March 23 questions above.[62]Rieger did not wait around for the Foundations reply, firing off letters to the California Secretary of State (23 Mar 1953), Los Angeles Bar Association (23 Mar), State Bar of California (03 Apr), … Continue reading In that April 14 reply “Mrs. Henry Hay” revealed herself to by Harry Hay’s mother and Mrs. Campbell to be the mother of Steve—the founders’ nickname for Konrad Stevens—which presumes Rieger was familiar with them both. Miss Cox, due to her husband’s illness, was being replaced by David Freeman—a pseudonym for Chuck Rowland (and, yes, Hay uses both of Rowland’s monikers in the letter). As for Mr. Snider, Hay wrote that Snider was looking into the Mattachine incorporation, which had been submitted about nine months before. “It is my understanding,” wrote Hay, “that this ordinarily takes a year or so”—an impossible time lag borne out by the fact that Rieger already had received a letter dated March 25 from the Secretary of State denying “any record whatsoever” of such a corporation and a follow-up dated April 10 explaining the office’s “policy to file promptly articles of incorporation […] provided of course they are in proper order.”[63]Jordan to Rieger, 25 Mar 1953; Jordan by Johnson to Rieger, 10 Apr 1953 (Lucas 1997 1:3). I am grateful to Mark Sawchuk for obtaining these. In fact, the Foundation’s articles of incorporation were dated ten months prior—June 7, 1952—but they had not been received by the Secretary of State as of the April 10 1953, as indicated above. They finally were filed by a deputy—presumably promptly—on April 27, 1953.[64]The articles of incorporation are available at the California Secretary of State Business Search using Entity No. C0273698. “I know nothing at all about Mr. Snider’s political affiliations,” Hay wrote, before divulging her own. “Personally, I have been a Republican for over fifty years. Incidentally, my husband once was a partner of Herbert Hoover, and we often visited the Hoovers in New York.”[65]All quotes are from Hay to Rieger, 14 Apr 1953 (Mattachine 2008 1:8). I am grateful to Jeff Snapp for obtaining this. I could find no mention of Harry Hay’s father Henry Hay Sr. in several … Continue reading As historian Lillian Faderman writes (2015, 68), “An idiot might have been taken in by this comically bogus letter; but Rieger was no idiot […].”[66]No reply to Hay by Rieger is in available archives. Indeed the only truth in the letter appears to be the parentage of Hay and Stevens as well as Margaret Hay being a long-time Republican.[67]California voter rolls from 1924 to 1952 list Margaret N. Hay as a registered Republican.

An Illusion of Democratism

On March 11, a day before Paul Coates’s column appeared in the Mirror, Chuck Rowland wrote Harry Hay, discussing the writing on the wall: “Whether you like it or not (whether I like it or not), the subject for today is REORGANIZATION.” He argued that clandestinity had outlived its usefulness in the brief 2¼ years of the Mattachine’s life such that “when the cry of reorganization is raised in our Jr. Chamber of Commerce Laguna Group (the exact type of group the secrecy of the Society was designed to protect) I am seriously concerned.” Anticipating pushback from Hay, Rowland wrote, “You will perhaps argue that we have insufficient experience on a national level, insufficient experience with the minority as a whole.” But Rowland recognized that they risked losing everything by maintaining the present trajectory. “I might agree with you—agree that we have a lot to learn—but I’d still say that our pioneering has created a whole, new situation and it is in this new situation that we must act and act intelligently or we will loose [sic] our leadership (paltry objection!), all our aims and purposes.” And Rowland had wasted no time of his own. “Friday I am introducing a motion that we […] call a Convention (see attached) and propose a Constitution (also attached, which I have written) and a set of Convention rules (I haven’t prepared them yet).”[68]Rowland to Hay, 11 Mar 1953 (Mattachine 2008 1:8). I am grateful to Jeff Snapp for obtaining this.

Chuck Rowland disappointed Harry Hay at least twice during their comradeship, this being the first, and memorialized in a letter to Mattachine cofounder Rudi Gernreich, ca. 1954–1955, in which he lamented Rowland and Bob Hull’s “change-of-heart” “culminating in a highly unrealistic illusion of grass-roots democratism, that wrecked the Mattachine idea.” In the letter, Hay invoked the names of Earl Browder (the CPUSA leader who spoke of capitalism and socialism coexisting and even collaborating[69]The Worker, 16 Jan 1944, 8, from Browder’s report to the Party’s national committee, 07 Jan 1944.), Stalin’s security chief Lavrentiy Beria (who in 1953 had been fired as vice premier, accused ostensibly and officially of “undermining the Soviet state in the interests of foreign capital.”[70]”Soviet Deputy Beria Ousted by Malenkov,” Los Angeles Times, 10 Jul 1953, 1.), and Arthur Koestler (novelist of Darkness at Noon, set at the end of Stalin’s purges and show trials of the 1930s, in which Beria participated and which Browder supported[71]See the speech Browder delivered in March 1938 regarding “the treason trial, just finished in Moscow, in which Bukharin, Rykov, Yagoda, Rakovsky, and their seventeen co-defendants revealed at last … Continue reading). Hay saw Rowland’s character as deeply flawed, not just transiently misguided. “I’m afraid the weakness in Chuck, though not necessarily in the Minority, is generic rather than circumstantial.”[72]Hay to Gernreich, n.d. but between 12 Apr 1954 and 11 Apr 1955 (Hay Papers 11:36). I explore dating of this letter in my manuscript. A month after Paul Coates’s column appeared, at the Mattachine’s inaugural constitutional convention, Hay would be vindicated when Rowland’s draft constitution was swept aside, as others had their own notions about “reorganization.”

¶ Prior articles in this triad are “Harry Hay Meets His Match” and “Blown Cover: The Arrest of Dale Jennings.”

References

Abbreviations: FBI = Federal Bureau of Investigation; ONGLA = ONE National Gay and Lesbian Archives at the USC Libraries

Alwood, Edward. 1996. Straight News: Gays, Lesbians, and the News Media. New York: Columbia University Press.

Browder, Earl. 1938. Traitors in American History: Lessons of the Moscow Trials. New York: Workers Library Publishers.

Calif. Assembly. 1950. Preliminary Report of the Subcommittee on Sex Crimes of the Assembly Interim Committee on Judicial System and Judicial Process. Pagination as published in the Assembly Journal: 1950 First Extraordinary Session, 08 Mar 1950, 29–298.

California Labor School. 1957. Once They Did It to Speak-easies, Now They Do It to Schools. San Francisco: CLS [as noted in cover letter from Holland Roberts, Director, 15 May 1957]. (SCL-20C, Box 8, Folder 5.)

D’Emilio, John. 1970s. Correspondence: Chuck Rowland. Interview notes: James Gruber, Harry Hay, James Kepner, Dorr Legg, Konrad Stevens, as listed below. In the possession of D’Emilio as of July and August 2009, and March 2014. I am grateful to John D’Emilio for providing me with copies of these documents.

——. 1976. Notes from interview with Harry Hay, 16–19 Oct 1976, San Juan Pueblo, NM.

——. 1983. Sexual Politics, Sexual Communities: The Making of a Homosexual Minority in the United States 1940–1970. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Faderman, Lillian. 2015. The Gay Revolution: The Story of the Struggle. New York: Simon & Schuster.

FBI. 1953 (09 Sep 1953). Two documents: 1) H. Rawlins Overton. Report: The Mattachine Foundation, Inc. […], ONE, Inc. Los Angeles. Case No. LA 100-45888. Declassified 02 Apr 1985. 2) S[pecial] A[gent in] C[harge], Los Angeles, to Director, FBI. Office Memorandum: The Mattachine Foundation, Inc. […], ONE, Inc. Internal Security – C. Declassified 06 Feb 1984. The latter document is a cover memo for the former 52-page report. The versions posted on the FBI’s Vault website are redacted differently from that posted on GovernmentAttic.org.

Hay, Harry. Harry Hay Papers, GLC 44, Gay and Lesbian Center, San Francisco Public Library. Boxes and folders in my text are rendered, e.g., Hay Papers 11:36. I am grateful to Tim Wilson (SFPL) for providing me with the finding aid for this collection in 2009 before it was fully processed.

Hurewitz, Daniel. 2007. Bohemian Los Angeles and the Making of Modern Politics. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Katz, Jonathan Ned. 1976. Gay American History. New York: Thomas Y. Crowell.

Kepner, Jim. 1998. Rough News, Daring Views: 1950s’ Pioneer Gay Press Journalism. Binghamton, NY: Haworth Press.

Lucas, Donald Stewart. 1997. Donald Stewart Lucas Papers, 1997-25, GLBT Historical Society. Boxes and folders in my text are rendered, e.g., Lucas 1997 1:20.

Mattachine. 2008. Mattachine Society Project Collection, Coll2008-016, ONGLA. Boxes and folders in my text are rendered, e.g., Mattachine 2008 1:20.

Merrill, LaRue H., ed. 1961. Brief History of Alma Merrill and Families. Self-published family history. Idaho Falls, Idaho.

Sears, James T. 2006. Behind the Mask of the Mattachine: The Hal Call Chronicles and the Early Movement for Homosexual Emancipation. Binghamton, NY: Harrington Park Press.

Timmons, Stuart. 1990. The Trouble with Harry Hay: Founder of the Modern Gay Movement. Boston: Alyson Publications.

Tuchman, Mitch. 1987. Radical Faerie Consciousness. Unpublished manuscript based on interviews of Harry Hay conducted by Mitch Tuchman in 1981, 1982, and 1985. Accessed in Hay Papers 1:15–16.

U.S. House. 1953. Committee on Un-American Activities. Investigation of Communist Activities in the Los Angeles Area—Parts 1–7.

Text by David Hughes. © 2018 David Hughes. All rights reserved.