Harry Hay Meets His Match

Harry Hay Meets His Match

by David Hughes

Posted January 4, 2018

A Triad: Part I

1952 was a watershed year for the Mattachine. The organization had begun its engagement with the larger community by standing in solidarity with Mexican Americans who, like homosexuals, were targets of the Los Angeles Police Department. With the arrest of its cofounder Dale Jennings in March of that year the Mattachine had a test case of its own to rally ’round, but in that effort the group turned inward rather than outward. I examine this dynamic in this first of three articles. I also look at the remarkable woman Harry Hay met along the way.

The gamble to back Jennings paid off. His superb legal representation—bankrolled by Mattachine fundraising—resulted in a hung jury, allowing the organization to capitalize on an impossible dream: an admittedly homosexual man beating a charge of lewd vagrancy. “Blown Cover: The Arrest of Dale Jennings” reviews some of the particulars of the case, including the identity of his arresting officers. I also examine LAPD’s liberal employment of the lewd vagrancy allegation as well as its use of a tactic known as the “third degree” and brutalization in general.

In the fall of 1952, emboldened by Jennings’s success in court, the Mattachine once again turned its gaze outward, this time to civic leaders and local candidates for office. The vehicle of outreach was a brief survey known to have been completed by only three or four respondents, but when it came to the attention of a local newspaper columnist, the concerns he voiced about the Mattachine turned out to reflect those already in the minds of its members, as discussed in “Queer Questionnaire and Coates Column.”

The following is adapted from my work-in-progress with the working title The Feeble Strength of One: Bob Hull, Chuck Rowland, Maxey, Marx and the Mattachine. Because its length likely would prevent its eventual publication as-is, I offer it here.

Abstract

In early 1952, leaders of the Mattachine became aware that the issue of entrapment of homosexuals by police in Los Angeles also affected Mexican Americans. In the latter regard the Mattachine was contacted by the local Civil Rights Congress (CRC), a Communist Party front group. The Mattachine also made an alliance with the Red-friendly Asociación Nacional México-Americana, which had its roots in organized labor but concerned itself with police brutality as well.

It was only five weeks after Mattachine cofounder Dale Jennings himself was entangled in an instance of entrapment, which consumed the efforts of the Mattachine, that cofounder Harry Hay began a dialogue with CRC secretary Shifra Meyers. We’re only privy to one side of that conversation, via a four-page letter to Meyers from Hay that pulled no punches and was curiously critical of an organization with which he and other Mattachine cofounders had been involved. Along the way we compare the California legislature’s then-current sex crime laws with the testimony of sexologist Alfred Kinsey. And we discuss the woman that Shifra Meyers would become after her involvement with the Civil Rights Congress.

Ultimately the Mattachine appears to have abandoned its engagement with other minority groups in favor of focusing both strategically and informationally on the cause of homosexuals.

Common Cause

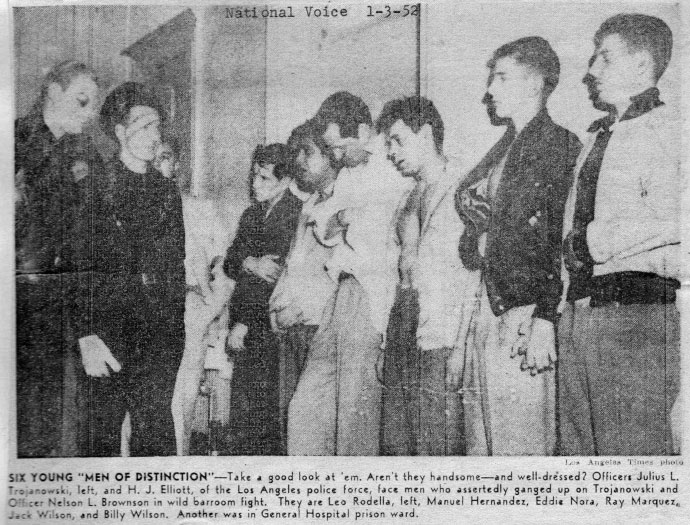

Mattachine cofounder Harry Hay recalled to historian John D’Emilio (1976) that, beginning in October 1951, police raided Mexican American organizations on the pretext of narcotics and gambling, with attendant beatings and brutality.[1]Hurewitz (2007, 259) repeats Hay’s story, using the same source. To my knowledge, such raids weren’t reported in the Los Angeles Times,[2]The Los Angeles Times did, however, report on instances of narcotics and gambling busts of Mexican Americans apart from “organizations.” See, e.g., “Five Arrested on Narcotics … Continue reading but two cases involving allegations of brutality towards Mexican Americans by drunken cops received much coverage from that newspaper in the winter and spring of 1952.[3]The first incident was the Dec 1951 “Bloody Christmas” case that figures in James Ellroy’s novel L.A. Confidential and its film adaptation; the second was the Jan 1952 brutalization of … Continue reading And the Mattachine was paying attention. On March 14, 1952, just a week before the arrest of Mattachine cofounder Dale Jennings, the issue of police brutality was raised at a Mattachine meeting (Gernreich Papers 112:1).

Chuck Rowland, another Mattachine cofounder, recalled making an alliance with residents of East L.A. who faced encounters with the LAPD:

As soon as we got into the oppressed cultural minority phase we had something our backgrounds had prepared us for—oppression of the blacks, the Jews, of women, and now—here in Los Angeles—of the Chicanos (who weren’t called that at the time). A left-oriented organization, ANMA (Asociación Nacional Mexicana [sic] Americana), was formed to oppose police harassment and frequent brutality in East LA. We would make common cause with them for, we were convinced, all socially oppressed minorities had something in common, whether they knew it or not.[4]Rowland to D’Emilio, 17 Jan 1977 (D’Emilio 1970s). ANMA’s correct spelling is Asociación Nacional México-Americana.

It can be said with a wink that ANMA already had made common cause with Mattachine leaders just prior to the latter organization’s formation, when ANMA circulated the Stockholm Peace Appeal,[5]Prof. Shana Bernstein (2011, 125) includes this in her profile of ANMA, citing Prof. Mario T. García (1989, 209). just as had Mattachine founders Harry Hay and Rudi Gernreich the summer of 1950 in an attempt to chat up homosexual beachgoers who might be interested in a campaign of their own (Timmons 1990, 142–143). But in 1952 the Mattachine would find itself preoccupied with rallying around its cofounder Dale Jennings just when it was reaching out to community members who, like gay men, had been targeted by the police. Harry recalled to historian John D’Emilio (1976) the “entrapment of Chicanos thru use of plainclothes in their community,” according to interview notes. Chuck Rowland told the historian at about the same time, “We did profit handsomely in recruiting several very fine gay Mexican-American kids to our banners.”[6]Rowland to D’Emilio, 17 Jan 1977.

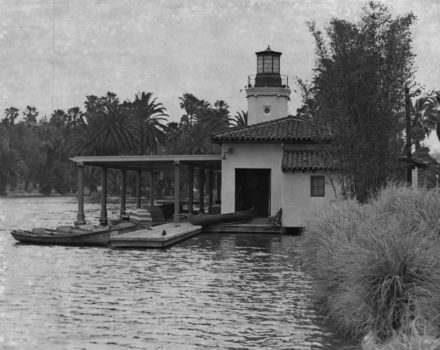

“Help, a queer!”: The Echo Park Boathouse

Hay’s recollection to D’Emilio above—“entrapment of Chicanos thru use of plainclothes in their community”—referred to at least one case.

The incident involved Mexican-American youths, and it was mentioned in two items issued by the Mattachine front group, Citizens’ Committee to Outlaw Entrapment (formed to support the case of Dale Jennings). “An Anonymous Call to Arms,” an undated, wordy, three-page polemic, states, “Corruption is a disease which requires ever larger and larger areas upon which to feed. Attempted entrapment can become attempted murder as it did on the night of January 27th, 1952 against five Mexican-American Youths in Echo Park.” The three pages weren’t exactly “anonymous,” having been issued by the Citizens’ Committee and signed by the group’s treasurer, Jean Dempsey, but the circular’s text does call the group “an anonymous body of angry voters.”[7]The Citizens’ Committee folder (Mattachine 2008 1:14) contains three actual entrapment case summaries, two of which were incorporated into the “Anonymous Call.” A second, single-page flyer is headlined “NOW is the time to fight”—to fight police brutality and entrapment—“while there is before the courts the case of the Mexican-American youths who defended their right to heterosexuality while a vice squad plainclothesman sought to charge them with lewd and indecent acts.”[8]Timmons (1990, 166) calls the first item a leaflet, but the version available to me consists of three full, single-spaced, letter-size pages. The second item appears to be a distillation of the first … Continue reading (Mattachine 2008 1:14) Had these defenders of heterosexuality been recruited to the Mattachine banners, as Chuck Rowland had recounted above? It’s an open question.

The case of the Mexican-American youths was reported by the Los Angeles Times first on January 28, 1952, as an attempted robbery of a man emerging from the Echo Park boathouse. That man was vice squad officer Ted Porter—the T. N. Porter who would be one of the officers involved in Dale Jennings’s entrapment two months later. The youths—four of the five had Spanish surnames—were reported by the police to have jumped Porter, kicking him, “and trying to take his badge”—a curious detail—“and wallet. As one of the men grappled for Porter’s revolver, the gun went off,” shooting 19-year-old William L. Rubio. The next day, the Times reported on an “investigation to ascertain if five arrested youths […] are ‘park bandits’ who have been preying upon lone men in Echo Park.”

A different story is told by an undated fact sheet prepared by the Echo Park chapter of the Civil Rights Congress. William Rubio, his brother Victor, Horace Martinez, and Frank Canales, all 17, were at the boathouse counter drinking coffee when Martinez went to the restroom in a nearby building. His seat at the counter then was occupied by William Arnold, 18, a friend of the others. As the four left the boathouse, they heard Martinez yell from the men’s room, first in Spanish, “Help, help, a queer!”

In the lavatory, Martinez had noticed an oddly behaving man dressed in work clothes staring at him. “What are you staring at?” he challenged the man. The man walked over and struck him. Martinez ran from the lavatory, yelling, “Help, help, a queer.”

The man ran after him. He knocked Martinez to the ground, and was beating him when Martinez’ four friends arrived on the scene. The man pulled a gun and at a distance of about eight feet fired at William Rubio. The bullet went through Rubio’s chest. He turned with the impact. A second man grabbed him, beat him on the head with a hard weapon. Dazed, Rubio wrenched loose, staggered, fell into the lake. Rising, he reeled onto the shore, tried to call his brother for help. He collapsed, unconscious.

The second assailant was Porter’s partner, an Officer Allen. “They arrested the youths, including a sixth who happened to be nearby,” according to the fact sheet. “William and Victor Rubio and William Arnold never reached the actual struggle. Arnold was stopped with a gun in his back.”

William Rubio, whose right lung had been pierced by the bullet, was taken by ambulance to the jail hospital after about an hour. The others were taken to the police station and booked on suspicion of robbery; the unnamed sixth youth was released immediately. Martinez and Canales were beaten by the police while handcuffed. “Within three days,” the fact sheet stated, “Victor Rubio and William Arnold were released and told by the police to ‘leave town’.”

Martinez and Canales were tried before Juvenile Judge William B. McKesson on charges of resisting and striking an officer rather than robbery and found guilty on the sole testimony of Porter. Canales was placed in the strict custody of his mother and Martinez was to have two weeks of psychiatric examination—as a suspected homosexual and/or deviant?—at the Biscailuz youth center. Rubio finally was transferred February 20 from the jail hospital to the Lincoln Heights jail where he bonded out two days later, claiming he’d been denied proper medical care and food.[9]All above details are from “Fact Sheet – Echo Park Shootings” (Civil Rights Congress 2:5).

Coffee, Cop’s Roost, Rolling a Queer

The Civil Rights Congress investigation, reported in its above fact sheet, found that four “ventilation holes” in the ceiling of the Echo Park Boathouse lavatory allowed surveillance from the attic and that, at the time of the shooting, two plainclothes officers were on the scene, on the sidewalk above the boathouse entrance.[10]“Fact Sheet – Echo Park Shootings.”

The CRC’s “Information Bulletin (1),” essentially a list of talking points, repeats the narrative of the fact sheet, but with some new details. The introductory paragraph calls the noise-dampening carpeted attic above the boathouse toilet a “cop’s roost” with “squared holes above the toilets in both the men’s and women’s sections.” The bulletin’s first section, Police Entrapment, states that the January 27 incident took place at about 9:00 that night. “At a time before [sic], Martinez had struck a ‘queer’ (homosexual) who had approached him for immoral purposes. Because of Porter’s odd behavior, he [Martinez] became hostile and asked him what he was staring at.” The bulletin ends with statements that “the police frame-up and brutality in the present case was [sic] directed against the Mexican-American youths only. It fits into the pattern of the increasing crime of genocide being committed against Mexican and Negro people.” (The CRC had written that the U.N. “defines genocide as any killings on the basis of race.”[11]The concept of genocide is applied from the U.N.’s genocide convention, as discussed in CRC’s book We Charge Genocide: The Historic Petition to the United Nations for Relief from a Crime of the … Continue reading) Demands in the bulletin included closing the “cop’s roost” above the toilets, ending police brutality and entrapment methods, and bonding officers to make them accountable for civil rights violations.[12]“Information Bulletin (1): To the People/ Echo Park Community” (Civil Rights Congress 2:5). I am grateful to Dr. Emily K. Hobson, Assistant Professor of History and Gender, Race, and Identity at … Continue reading

An undated record of an account by William Arnold states that he told police, “The five had robbed a ‘queer’ right before the mentioned incident. Then they went to the boathouse for coffee. In the boathouse, they saw officer Porter (in plainclothes). William Rubio said: ‘I’m going to slug this fellow’.” (Civil Rights Congress 2:5)

A February 2 statement signed by Victor Rubio, brother of William who had been shot, contradicts Arnold’s statement. As a minor at age 17, Victor had been interrogated by a “juvenile policeman” after which Arnold was brought into the same room. “The adult policeman asked William Arnold, ‘Who got the idea of rolling a queer. [sic]’ William said that all [of] us did. The policeman then asked me if that was right,” Victor wrote in his statement. “I told him, ‘No, we had no such idea.’ We had never talked about anything like that.” (Civil Rights Congress 2:5) At the very least there’s the ironical implication that the Mattachine’s Citizens’ Committee was engaged in solidarity with youths who preyed on gay men.

CRC, Meet CCOE

On April 28, 1952, under the manually typed letterhead of the Citizens [sic] Committee to Outlaw Entrapment, Harry Hay, using the pseudonym Joseph Harrison, wrote Shifra Meyers, Administrative Secretary of the Civil Rights Congress.[13]Hay’s authorship of the letter under the name Joseph Harrison is identified by his distinctive handwritten edit on p. 3 as well as his signature on p. 4. Meyers is identified by CRC letterhead on a … Continue reading Meyers had contacted the Citizens’ Committee and spoken with Hay by telephone, according to the letter, which was a follow-up to that conversation after he had consulted with the Committee. Coincidentally, a CRC meeting was scheduled for two days later to protest Rubio’s boathouse shooting and the knifing of Henry Hernandez by Officer F. F. Nájera; both citizens were to face trial on charges of resisting arrest and assault on May 7.[14]“CRC meeting will describe cop brutalities,” Daily People’s World, datelined 28 Apr 1952, 6 (Civil Rights Congress 2:5). See also “Slugged Policeman Stabs Assailant,” Los Angeles Times, 25 … Continue reading Hay begins his letter to Meyers by saying he’s enclosing copies of “the minute amount of material produced as yet by our newly emerged committee” without identifying the enclosures. He then responds to his earlier telephone conversation with Meyers:

We were a little non-plussed to hear your outfit didn’t seem to know what to do with the entrapment case on your docket. We cannot quite imagine how the myriad facets of civil encroachments, which are packed into practically every entrapment case, can have escaped your notice. (We were a little amused at the gaping wide-eyed wonder expressed by one of our more liberal local sheets, (published in S.F.)[15]If S.F. stands for San Fernando Valley, Hay might refer to Van Nuys News, but I’m unable to find mention of a case involving police decoys in that newspaper. which said, in effect, IN THIS CASE it seems that the police decoy actually made all the advances. Why this particular paper should have insisted over many years that while police relations with Mexican-Americans and Negroes were perjuries out of the whole cloth on the other hand what they had to tell about Homosexual arrests were true,——such sectarian naiveté is beyond our comprehension.) We can only pray that you won’t fumble the ball at this highly unique time in community-police relations.[16]Hay to Meyers, 28 Apr 1952 (Civil Rights Congress 2:5). Unless otherwise referenced all quotes are from this letter.

After listing eight common torments perpetrated by the police against homosexuals, Hay writes,

As you mentioned on the phone, you didn’t know about these things. Why should you have known about them? What have you ever offered the Homosexual that he should risk his livlihood [sic], his housing, even his pitiful facsimile of social security, to inform you? Has any committee and/or group of civic or sectarian minded citizens ever taken even an impartial interest in the Homosexual Minority as a Group? Has the homosexual EVER had anyone to turn to, (except the dubious subjectivity of his own), for help, succour, guidance, protection, or sympathy? Unfortunately well-meaning people like yourselves are still so shot through with Freudian conditioning that you cannot perceive the Homosexual as a member of a social minority.

Then, perhaps especially because he knows he’s writing to a member of the Communist Party, Hay launches into a recitation of Stalin’s definition of a minority (without attribution).[17]See this translation of “Marxism and the National Question,” 1913, in which Stalin states that a nation (what Hay referred to as a minority) is “a historically constituted, stable … Continue reading The lecture continues for three more pages. But Hay makes several points along the way.

“Under the penal code of the State of California […] section 647.5, a Homosexual is guilty of a status rather than an act.”[18]§ 647.5 of the California Penal Code appears to have been repealed subsequent to Hay’s citation. § 647 on the whole deals with lewd conduct, sex work, etc. See this reference, accessed 11 Nov … Continue reading

The “equating of Homosexuals as automatically lewd and dissolute persons has its counterparts in two other stereotyping equations that come to mind….each of these also carefully emphasized by the police and certain sections of the press. One is,—that all Mexican-Americans attend gatherings and dances armed to the teeth with knives and razors […]. The other is,—that all Negroes are usually drunk and disorderly when not working […].” Continuing:

You have so allowed yourselves to become immersed in the big lie that the “Homosexual” (stereotype) exists only to corrupt the youth,[19]Assemblyman William Rosenthal had raised this supposition, discussed below.—that the simple fact that Homosexuals, like all Minorities, actually seek and prefer the company of their own kind escapes you. Indeed, the assembly bans of the Black Belt, in force from about 1821 to 1863, whereby no three Negroes might speak with each other without a whiteman’s presence, are now in related form applied to us. Never enabled to meet each other in decency and in social dignity, we are all driven by you into varying fantasies of despair and distortion. For some the lonliness [sic] and despair becomes [sic] desperation. And for him, made socially sick and infectious….yet still my brother, defiance and belligerence are the only answers. The chances are good that the boys involved in your entrapment case belong in this category.

Does Hay insinuate that the Echo Park boathouse youths, behind their defiance and belligerence, were repressed homosexuals? If so it is of interest in light of the fact that, as noted above, Hay’s Citizens’ Committee issued a leaflet (“NOW is the time to fight”) stating that those same youths “defended their right to heterosexuality while a vice squad plainclothesman sought to charge them with lewd and indecent acts” (Mattachine 2008 1:14).

On page 3 of his letter, Hay plays the Lavender-Red card, arguing that a roundup of political undesirables could be applied to sexual miscreants as well. He also warns that the commandeering of private enterprise under a planned (but to this point only looming) wartime mobilization of the entire private sector by the U.S. government would necessarily flush homosexuals out of the new quasi-governmental operations.

Does it not occur to you that, in light of the fact that as Harry Bridges says “you cannot PROVE that your [sic] are not what you are not”, that between the State and Federal McCarran Acts and the Homosexual Lewd Vagrancy statutes a reactionary administration can gag the population in a way that leaves the most innocent citizen defenseless? Perhaps, this seems too far-fetched for you. Consider for a moment the identicals in both the McCarren and the Lewd-Vag statutes. First, they both lead to registrations[;] second, under them both the victim is guilty of a status until he can prove himself innocent; third, under both statutes he can be declared guilty by association. Coincidental, perhaps. Many reactionaries say the Nazi’s [sic] choice of the Jews as scapegoats was a mistake. Their persecution aroused too much foreign sympathy. Would Homosexual persecution, or persecution of persons WHO COULD NOT PROVE THEY WEREN’T HOMOSEXUAL AT LEAST BY ASSOCIATION, arouse organized world sympathy? Surely your’re [sic] aware of the indictment in the State Department Cases? (Which has now silently spread to the Departments of Commerce, Agriculture, Treasury, and the Post Office[.]) The indictment, in effect, says that under complete mobilization of this country no Homosexual, or person acquainted with Homosexuals, may be employed by any company engaged in governmental work or contracts BECAUSE HIS PRIVATE LIFE AND/OR ASSOCIATIONS LEAVES [sic] HIM WIDE OPEN TO BLACKMAIL BY A FOREIGN POWER. By this opinion alone, the Truman Administration paved the way for creating one of the largest armies of destitutes in the world today. Talk about a pattern for Genocide! Brother! Under mobilization, these people, denied employment, vilified by fabricated hysteria and unhistorical prejudice into fearful isolation from the community, could be starved into serving many of the anti-social purposes you now accuse them of. Out of a similar contrivance the SS Guard of Hitler Germany was formed. Our Citizens’ Committee, amongst other things, assumes the grave responsibility of initiating the counter-effort against such a monstrous contrivance being repeated here. However, we must point out to you that an accurate measure of your own ignorance and prejudice, which encourages the continuance of our second-class citizenship as a Minority, is revealed by the fact that your own organization, in existence at the time of the State Department Indictments, did not speak out against this slanderous distortion. AT LEAST IN TERMS OF THE SLANDER IMPLIED AGAINST THE SOVIET UNION.

Hay’s letter to Meyers is dated almost a year to the day before President Dwight Eisenhower signed Executive Order 10450 on April 27, 1953, tasking government department heads with rooting out security risks, using criteria such as “sexual perversion” (Eisenhower 1953). Yet, as Hay mentions, homosexuals already had been forced out of the State Department. The public first got wind of this on February 28, 1950 when Secretary of State Dean Acheson’s deputy undersecretary John Peurifoy testified before a Senate appropriations subcommittee, that out of 202 employees who were allowed to resign as security risks in the prior two years, nearly half—91—“were homosexual cases, explaining that such persons are rated bad risks because they might be blackmailed as spies,” as AP put it.[20]“Senators Hear Acheson Deny Condoning of Hiss: Group of Questioners Told State Department Ousted 91 for Immorality in Last Two Years,” Los Angeles Times, 01 Mar 1950, 1. Disingenuously, Hay berates the CRC for not speaking out on behalf of that homosexual minority, when he himself had resigned from CRC’s de facto parent organization, the Communist Party, over what he perceived as the risk that he, as a homosexual, posed to the party’s own security, just months before writing Meyers. As Hay told his biographer Stuart Timmons (1990, 159), “Since homosexuals were forbidden membership in the Party, according to its own constitution,[21]No explicit reference to homosexuality is in the party’s 1948 constitution, the latest version available to me that also is dated prior to Hay’s letter to Meyers. Nevertheless, Article VIII, … Continue reading I felt that those members in California who knew my Party work would know I had never endangered Party security. But, were this matter [of Hay’s Mattachine activism] to be aired in the People’s World or the Daily Worker, members in other states might feel the Party had been lax about safeguarding the membership. I felt that a proposal for my expulsion would exonerate the California Party in their eyes, and that was the important thing.” Continuing, to Meyers, Hay writes,

We wish to make it emphatically understood, however, to all inquirers that we do not wish to ally or coalesce with prominent individuals, parties, or groups. We have learned through many years of bitter experience and betrayal that under current pressures, and constant revivals of mythical distortions, that the only cornerstones to which we can adhere are our own self-interests. It is true that our own self-interests differ in general pattern not one iota from the confluent patterns of other oppressed Minorities; nevertheless though our struggle embraces members of all other Minorities, other Minority struggles do not embrace us. American Minority groups are conditioned by the same ignorant hates, and prejudices, as is the community generally. To any such group, our Minority would be tantamount to the “kiss of death”. May I quote you an example of how maintaining our own self-interests, (with the long range objective of preserving the community best interest as previously outlined with regard to the real meaning behind the administrative fulminations against us), might run counter to immediate short-term goals of other sections of the community[?] Many of us, who are close to the Committee, are glad that William Rosenthal is not running for re-election to the California Legislature. It may be true that his pro-labor record was better than some. Nevertheless, his almost infantile bigotry, let alone his grammar-school approach, toward mountains of honest scientific inquiry and evidence, his Tenney-like affrontery [sic] towards hosts of honest scientific workers and authorities, as Chairman of the Legislature’s Interim Committee on Sexual Crime Legislation,[22]Rosenthal was a member of, not the chairman of, the Subcommittee on Sex Crimes of the Assembly Interim Committee on Judicial System and Judicial Process. Rosenthal was the vice chairman of that … Continue reading may have opened California to a rash of the most reactionary and potentially fascist statutes, in the guise of sex laws, that any community has every seen. Certainly his “do pass” on the H. Allen Smith bills, notably ABs 15, 16, 17,[23]Smith (R-Glendale) also introduced Assembly Bill 31, as documented in Assembly Final History: 1952 First Extraordinary Session, 86. I discuss this below. has given the State the right to establish concentration camps for between 500,000 and 1,000,000 people anytime the State wants to move. How does the State do it? Very simple. By entrapment, by rounding up the registrations already produced by previous entrapments, and by shadowing and hounding the unsuspecting victims whose names and addresses they have collected through intimidation. No, Miss Meyers, we would do everything in our power to mobilize our Minority to vote against Rosenthal if he ever shows his yap in the public market-place again. The leopard doesn’t change his spots. Such stupidity and viciousness cannot be expected to be regulated only against us. Of such scantily-noticed specifics are potential Yortys made.

If Hay’s remark might seem prescient regarding Sam Yorty, Los Angeles’ future demagogic mayor, here’s how the Los Angeles Times once summarized Yorty’s career up to this point: “Oddly, Yorty began as a liberal defending labor unions and fighting for better working conditions, attracting left-wing support for the various offices he sought. But after 1938, when he lost that following to Fletcher Bowron, who had just been elected mayor, Yorty talked about ‘labor misleaders’ and became a prominent communist hunter.”[24]“Three-Term L.A. Mayor Sam Yorty Dies at 88,” Los Angeles Times, 06 Jun 1998, A1. Indeed, historian Edward Barrett (1951, 1–10) sees the now-forgotten Yorty Committee of the California Assembly as the progenitor of the infamous Tenney Committee that investigated California communists in the 1940s. Yorty himself introduced H.R. 2 on January 30, 1940 to establish a Relief Investigating Committee to deal with “improper practices in connection with the administration of unemployment relief.”[25]Assembly Journal: 1940 First Extraordinary Session, 58. Because the State Relief Administration was “the one large state agency not covered by civil service,” Democrats and Communists were battling in that agency for power and the patronage of the newly installed Governor Culbert Olson—the first Democrat in that office since 1899 (Barrett 1951, 2). On February 2 of 1940 Yorty was appointed chair of the RIC, with Tenney as one of its members.[26]Assembly Journal: 1940 First Extraordinary Session, 116. By contrast, the year before, Tenney had coauthored H.R. 27, which called upon FDR to revoke the arms embargo against Republican Spain;[27]Assembly Journal: 1939 Regular Session, 106. Yorty voted for it. The same year, Tenney authored two anti-Redbaiting bills. But just as Yorty had lost his luster to Fletcher Bowron, when Tenney was defeated in his American Federation of Musicians Local 47, he scapegoated communists. (Barrett 1951, 6) Only ten days after the Yorty committee’s formation in January 1940, it issued a seven-page report that led off, “The Communist party is now, and has for the past two years, at least, successfully followed a plan of infiltration into the State Relief Administration with a view toward domination of same.”[28]Assembly Journal: 1940 First Extraordinary Session, 209. The same committee’s detailed, fifty-page report, issued May 24, 1940, reads like the template for what Tenney would produce throughout the coming decade. The thrust of the argument is that the Russian-run Reds’ “fifth columns” were not just passively waiting for a crisis, but that the CP cadre in the SRA was actively exacerbating the unemployment situation by increasing relief costs to an unsustainable level. Once relief ceased: revolution.[29]Assembly Journal: 1940 First Extraordinary Session, 814, 816.

Above, in Hay’s letter, he begins his example of how homosexual self-interests might clash with other community concerns, not with Yorty, but with charges against Assemblyman William H. Rosenthal, the labor-friendly legislator who apparently was not a critical thinker when it came to matters of sexuality and criminality—breathtakingly so.

Forbidden by Statute

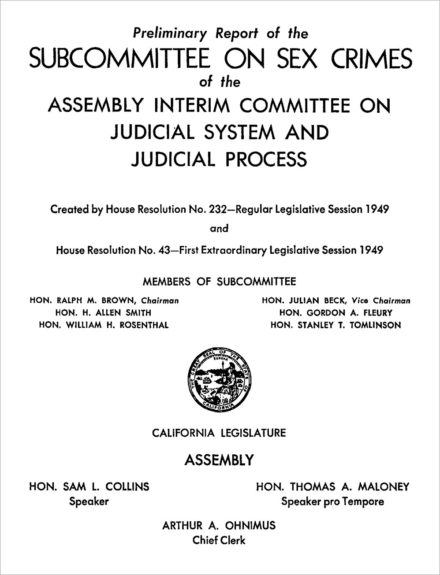

Shifra Meyers, with whom Harry Hay was communicating, lived in East L.A.,[30]“Shifra Goldman, 1926–2011, Champion of Modern Mexican Art,” Los Angeles Times, 20 Sep 2011, AA4. and thus Assemblyman William Rosenthal represented her district for ten years, from 1943 to 1953. Rosenthal, a New York native,[31]California Death Records, 1940–1997, accessed 27 Jun 2016 (since decommissioned). graduated from Southwestern University Law School in Georgetown, Texas. His further schooling was in constitutional law at Loyola in Los Angeles, and there he joined the city attorney’s office. As an assemblyman, one of Rosenthal’s early field representatives was Ed Roybal, who in 1949 would be the first Hispanic elected to Los Angeles City Council since 1881. After retiring from the Assembly in 1953 Rosenthal became chair of the Democratic State Central Committee and in 1959 was appointed by Governor Brown to a municipal court judgeship and later to superior court.[32]Biographical details from “W. H. Rosenthal; Former Judge, Assemblyman,” Los Angeles Times, 26 Mar 1991, A26. At the time of Hay’s letter to Meyers, Rosenthal had been on the Assembly Judiciary Committee since he took office in 1943[33]Assembly Final History: 1943 Regular Session, 29. and was made vice chair of that committee in 1947.[34]Assembly Final History: 1947 Regular Session, 34. He had been a member of the Interim Committee on the Judicial System and Judicial Process since its formation in 1947[35]Assembly Final History: 1947 Regular Session, 41. and had been on that committee’s Subcommittee on Sex Crimes since its inception in December 1949.[36]Assembly Final History: 1949 First Extraordinary Session, 105. After several hearings in the late fall and early winter of 1949–1950, the subcommittee issued a preliminary report, published March 8.

The report is surprisingly candid. Its foreword explains the subcommittee’s raison d’être—public fixation on sensational murders—even as testimony in the report itself—a trend toward “elimination of sex law”—calls the need for concern into question. Nonetheless, the rabble ruled the day. “Two small children were murdered by sex fiends in Southern and Central California in the fall of 1949,” begins the report’s foreword. “The publicity of these murders focused the attention of the public upon sex crimes and sex offenders. There was much public opinion that the size of the sex crime problem was such that existing legislation and techniques of control were inadequate.” And in passing: “Most of the sex practices known to man are forbidden by statute.” The report looks at those statutes and penalties of other states, discovering that punishments “do not follow a logical pattern”—e.g., sodomy: “punishable in two states by a term of life imprisonment; whereas three states have a maximum term of only three years.” And the report highlights the remarks of Alfred Kinsey, who appeared before the panel on December 14, 1949, reporting on trends: a “lessening of punishment,” the “elimination of sex law,” and identifying and treating psychiatric cases as is done with the insane. (Calif. Assembly 1950, 39, 40, 41) Bucking any trend however, immediately following Kinsey’s testimony the full Judiciary Committee recommended that the legislature enact “sharper” penalties, as AP put it, including doubling the penalty for sodomy for up to twenty years.[37]“Sharper Sex Laws Win Endorsement,” Los Angeles Times, 15 Dec 1949, 18. Three days later, the California Senate essentially handed the governor five sex crime bills with enhanced penalties, including death. Gov. Earl Warren, who would be appointed Chief Justice of the United States Supreme Court in 1953, signed all five bills into law on January 6, 1950.[38]“Senate Votes Death for Sex Crimes,” Los Angeles Times, 18 Dec 1949, 1; “Five Sex Crime Bills Get Warren Signature,” Los Angeles Times, 07 Jan 1950, 5. One, A.B. 37, the sodomy bill sponsored by Allen Smith, Rosenthal’s colleague on the Subcommittee on Sex Crimes, was officially described as “An act to amend section 286 of the Penal Code, relating to the crime against nature.”[39]Assembly Final History: 1949 First Extraordinary Session, 87. If the people wanted blood, they got it.

As noted above, the Subcommittee’s preliminary report was issued on March 8, 1950, nearly three months to the day after Governor Warren had signed five sex crime bills. AP, in its coverage of the report, wrote, “The State Legislature was today told that California has adequate laws on sex crimes—but they are not being enforced.” The report attenuated further, per AP: “California has not been ‘engulfed’ by a wave of sex crimes. The percentage of offenses perhaps has even dropped in proportion to the rise in population. […] Studies indicate that making the laws tougher is not a solution.”[40]“Sex Laws Held Adequate if They Were Enforced,” Los Angeles Times, 09 Mar 1950, 19. What’s a legislature to do? In the case of California, introduce more sex crime bills, accomplished in the summer of 1951. Subcommittee member Allen Smith proposed A.B. 2367,[41]Assembly Final History: 1951 Regular Session, 743. a “knife-or-life” bill that would allow sex offenders to choose castration voluntarily rather than life imprisonment, but Gov. Warren vetoed that idea while embracing the bill’s other life penalties.[42]“Knife-or-Life Sex Bill to Be Vetoed,” Los Angeles Times, 18 Jul 1951, 2. Warren signed A.B. 2874,[43]Assembly Final History: 1951 Regular Session, 834. Subcommittee member William Rosenthal’s bill that “provides that annoying or molesting a child constitutes vagrancy by increasing from 14 to 18 years the age of a person considered to be a child,” as UP described it.[44]“Warren Signs Bill to Curb Sex Crimes,” Los Angeles Times, 26 Jun 1951, 8.

Allen Smith chaired the Sex Crimes Subcommittee in the fall of 1951 (Calif. Assembly 1952) when it was tasked with another hearing on the adequacy of legislation.[45]“Assembly Unit Sets Session for Sex Crime Study,” Los Angeles Times, 22 Nov 1951, 26. The result was four new bills introduced by Smith in March 1952; these were the three bills highlighted by Hay in his letter to Meyers (A.B. 15, 16, 17), plus one more.

- A.B. 16, cosponsored by Rosenthal and signed into law, prohibited offenders from using classification as a psychopath to avoid the death penalty (Calif. Assembly 1952, 18).

- A.B. 31 (not cosponsored by Rosenthal[46]Rosenthal was granted leave of absence on 13 Mar 1952, the day A.B. 31 was introduced (Assembly Journal: 1952 First Extraordinary Session, 170).), signed into law, stipulated that offenders could not be employed by school districts (Calif. Assembly 1952, 42).

- A.B. 17, cosponsored by Rosenthal, was a new “knife-or-life” bill that had been carved out of 1951’s A.B. 2367, but it died in the Senate (Calif. Assembly 1952, 57).[47]“Sex Crime Bill Killed,” Long Beach Independent, 27 Mar 1952, 22-A. “Castration bill has been killed,” wrote Rudi Gernreich in his notebook of Mattachine meetings on March 28, 1952, the same meeting at which Dale Jennings’s entrapment case was discussed. Earlier, in the entry for February 15, Gernreich wrote, “Postcards protesting castration bill by other guild: to be signed when ready.” In the midst of preparation for a March 17 city hall hearing on police brutality,[48]I discuss this meeting, which Mattachine representatives supposedly attended, in my manuscript. Gernreich’s March 14 entry states, “Smith bill [sic]: 3 bills available[.] County Building Room 300 – four form letters to ministers, doctors, psychiatrists, lawyers – in the name of Society. – Report on bills – Joe, Lynn, Bob. – For next meeting.” (Gernreich Papers 112:1)

- A.B. 15, cosponsored by Rosenthal and signed into law, changed the penalties for several sex crimes, including rape, as well as Rosenthal’s earlier expansion of vagrancy. The bill’s most arresting components were those that appear to have disturbed Harry Hay, and indeed any sexual being who was paying attention. From the California Assembly summary of the bill:

Changes the penalty for crime against nature from 1 to 20 years imprisonment to an indeterminate sentence with a minimum of one year.

Changes the penalty for one convicted of participating in an act of oral copulation from the present minimum imprisonment of one year in the county jail with a maximum imprisonment of 15 years in the state prison to an indeterminate sentence with a minimum of three years imprisonment in the state prison when the person convicted is more than 10 years older than his coparticipant which coparticipant is under the age of 14, or when the person convicted has compelled participation by force, violence, duress, menace, or threat of great bodily harm. (Calif. Assembly 1952, 42)

The summary’s first paragraph above is plainly chilling; the amended code itself more so, referring to the “infamous crime against nature, committed with mankind or with any animal” as if citing scripture (Calif. Assembly 1952, 39; emphasis mine). The second paragraph requires close reading. Oral copulation by itself already carried a penalty of one year; the revision merely enhanced the penalty for performing the act on children or doing so via coercion. The summary’s next paragraph involves repeated conviction of lewd conduct, which was raised to the level of felony:

Makes a violation of the section prohibiting willfully lewd conduct a felony in the case of second and subsequent convictions for indecent exposure or in the case of a first such conviction following a previous conviction for lewd and lascivious acts involving children, the sentence to be indeterminate but to be not less than one year. (Calif. Assembly 1952, 42)

This summary paragraph does not delineate the many flavors of lewd conduct prohibited in the amended code: obscene literature, figurative art, poetry, and song (Calif. Assembly 1952, 40). As the Sex Crime Subcommittee wrote in its preliminary report two years earlier, “Most of the sex practices known to man are forbidden by statute” (Calif. Assembly 1950, 40). And while Harry Hay was justly enraged at the prohibition of practices in which the Homosexual Minority engaged, neither William Rosenthal nor Allen Smith were the original authors of Section 286 of the Penal Code, which governed the “infamous crime against nature.” They did, however, take advantage of public concern following the deaths of children. Designating lewd conduct as a felony and establishing a life sentence for anal sex, not to mention maintaining the one-to-fifteen penalty for a blow job sent a clear message to members of the Mattachine.

Knowing that Shifra Meyers would be aware that camps already had been readied for Reds under the McCarran Internal Security Act of 1950,[49]It was opined in early 1952 that the liberal wing of the Democratic Party, including Sen. Humphrey of Minnesota, had inserted the detention language in the original bill (named after its chief … Continue reading Hay extrapolated in his letter to her as quoted above: the sentencing enhancements of Smith’s bills “ha[ve] given the State the right to establish concentration camps for between 500,000 and 1,000,000 anytime the State wants to move.” Neither Reds nor homosexuals were rounded up en masse, but Assemblyman Rosenthal’s questioning of sexologist Alfred Kinsey in 1950 offered up such a roundup scenario, and Hay referred to this in his excoriation of the legislator in that letter to Meyers.

The Kinsey Retort

Sexologist Alfred Kinsey appeared before the Sex Crime Subcommittee in Sacramento on December 14, 1949.[50]“Crime Bills Are Approved,” Berkeley Daily Gazette, 15 Dec 1949, 14. All quotes from this hearing appear in Calif. Assembly (1950, 133–152). The transcripts of all witnesses’ testimony, … Continue reading At one point, the discourse turned to the success rate for castrated sex offenders: out of fifty in Los Angeles County, none had been charged again. Kinsey offered, “I think it would be important to point out to you that recidivism among sex offenders is lower than it is in any other criminal group, taking the country as a whole.”[51]I have not fact-checked this or Kinsey’s other claims made in the hearing and would welcome any input. Regarding exhibitionists, Department of Corrections Director Richard McGee, appearing with Kinsey, stated that “next to first-degree murder parolees, the violators of 288, are the best risks on parole. We have about 12 percent of violations, and of those, very few of them are violators by reason of having committed another sex offense.” To which Kinsey responded, “You see, for that reason your statement from Los Angeles that few of these people return isn’t necessarily cause and effect.” William Rosenthal then launched into the exchange that piqued Harry Hay’s ire regarding the internment of the Homosexual Minority.

Mr. Rosenthal: Let me ask you a question. In view of that statement, Doctor, it seems to me that the arrest of a particular offender and incarceration has had a good effect insofar as the courts are concerned. In effect, what you are saying is that the arrest and incarceration of a homosexual is one of the ways of keeping him from doing it again. Now, he may do it again, but not be arrested for it.

This is an example of what Hay called “Rosenthal’s almost infantile bigotry,” and a “grammar-school approach,” since he was so easily corrected by Kinsey.

Mr. Rosenthal: For that 4 percent of the population that are homosexuals, incurably so, that are at least that way forever and anon, isn’t that [prison] the only place for them? If we consider that since the crime can not be cured: they will inevitably remain homosexual.

Dr. Kinsey: What is the population of your State?

Mr. Rosenthal: Ten million.

Dr. Kinsey: […] All right, you have 160,000 males in this State whom you would have to consider incarcerating for the rest of their lives. Now, you have 8 percent of the population who is nearly homosexual or completely so; that means 320,000 of them.

[…]Mr. Rosenthal: One question following that. Is it true as we have heard that a homosexual invariably resorts to a younger person for his practices?

Kinsey’s answer doesn’t have to be repeated here. But on the question of incarceration, 21st-century readers of the above exchange can’t help but observe that large numbers have been imprisoned for reasons just as arbitrary as a crime of homosexual engagement—recreational drug use comes to mind—, to the point that the U.S. has a prison population that dwarfs every other country.[52]“Highest to Lowest – Prison Population Total,” World Prison Brief by Institute for Criminal Policy Research, accessed 17 Oct 2016. Inmates incarcerated for drug offenses dwarfs all other … Continue reading

Near the end of the session with Kinsey, Rosenthal followed up:

Mr. Rosenthal: Do you think that it is essential at this time or at any time, or beneficial, that the present penal laws be increased, as a way of retarding the apparent growth of sex offenders? Such as increasing the penalty from 10 years to 20, or castration, or segregation, or life imprisonment, or the gas chamber? Do you think that would retard it?

Unfortunately Kinsey does not respond to Rosenthal’s remark regarding “the apparent growth of sex offenders.”[53]One table included in the Sex Crime Subcommittee’s preliminary report’s Appendix, Summary of Sex Crimes Reported by California Sheriffs’ Offices and Police Departments, 1946–1949, shows sex … Continue reading As mentioned above, whereas Kinsey recommended leniency, the subcommittee’s parent Judiciary Committee (including Rosenthal) responded by sharpening sex crime penalties. Eight months after Hay’s letter to Meyers, Rosenthal received a thank-you plaque from judges of the Los Angeles Municipal Court: “For untiring efforts to improve the administration of justice.”[54]“Judges Give Rosenthal Scroll at Ceremony,” Los Angeles Times, 12 Dec 1952, 20.

Regarding Rosenthal’s “Tenney-like affrontery towards hosts of honest scientific workers and authorities,” as Hay depicts it in his letter to Meyers, such insolence is not evident in the subcommittee’s preliminary report, since Rosenthal’s questions and comments appears only in the transcript of Kinsey’s testimony, not in that of a dozen of other witnesses. Perhaps Hay had access to additional sources.[55]The only report known to me that contains interrogation of witnesses by William Rosenthal on the subject of sex crimes during 1949–1952 is the 08 Mar 1950 Preliminary Report of the Subcommittee on … Continue reading

Turning back to Hay’s letter:

From the tone in your voice, Miss Meyers, I detected an over-tone of patronage towards my firm stand on the need of anonymity as regards the personnel of the Committee. We must point out that when members of other minorities are harassed or terrorized,—historical experiences teach us that community groups rally round, their own Minorities naturally respond, their families close ranks in front of them. And they find an area of strength, of sympathy, of protection, and always comfort. This does not happen with us. Even our closest and apparently respectful heterosexual friends do not stick their necks out for us. Even if we are proven innocent in the course of events,—the “a-priori” judgements of the press have neatly disposed of our jobs (thus negating any hope of decent future employments which require references), our housing and, many times, our social relations.

In light of the above, though there do happen to be a number of persons on our Committee who are not members of the Homosexual Minority, perhaps you can grasp some understanding of our problems, and some understanding of the ways in which we must work. Our motivating objective in this beginning period of our activity is the securing of First-Class citizenship for all of our own brothers and sisters, and thus by statute and practice for all Minorities. Our efforts and our strengths are turned primarily to the furtherance of our own self-interests, following the dictum of Frederick Douglass who said, in 1883 before the National Convention of Colored Men, “Who would be free, themselves must strike the blow……the man outraged is the man to make the outcry.”

Until police brutality,…..morally, psychologically, socially, as well as physically is permanently outlawed against our Minority,—the lowest rung on the community ladder,—…..none of you and yours can hope to escape. May your prosecution of entrapment be a first blow in the struggle for all our freedoms.[56]All quotations are from Harrison to Meyers, 28 Apr 1952 (Civil Rights Congress 2:5).

Given Harry Hay’s approach above, it may be no surprise that fifty-five years later, in his portrait of Hay’s neighborhood, Bohemian Los Angeles, Daniel Hurewitz (2007, 261) writes, “The Mattachine members did not convince the Civil Rights Congress to act on their behalf.” In one respect, Hay’s four-page letter to Shifra Meyers can be viewed as being protracted, didactic, sarcastic and, frankly, snotty, considering he was addressing an official of a CP front group with which he and other Mattachine founders had been involved.[57]As reported by the FBI, Hay’s name “was, as of October, 1950, maintained by the CRC in Los Angeles.” However: “Informant was unable to advise as to the significance of this information.” … Continue reading Was Hay reciprocating for the cold shoulder he’d received by former comrades following his altruistic departure from the Party (Timmons 1990, 159–161)? My hunch is that Hay had met his match in Shifra Meyers, but this is based on the reputation she would build over the coming decades. Hay’s response to Meyers in his letter is a protracted and articulated rebuttal of a conversation the two had by telephone some time in April 1952. His veiled vituperation might reflect the strength of Meyers’s arguments but, of course, it simply could be a response to her ignorance and intransigence. (If only the FBI had tapped this particular phone call….) Undeniably, Shifra Meyers was to become, like Harry Hay and the Mattachine, a groundbreaker.

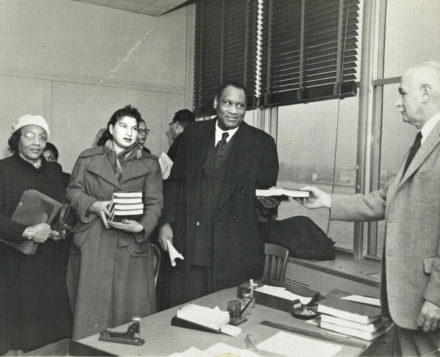

Shifra Meyerowitz García Goldman

I met Shifra Goldman[58]I am grateful to my wife Andrea Carney for pointing out that the Shifra Myers of the Civil Rights Congress in the 1950s was the Shifra Goldman that I met in 1991. Andrea located Goldman’s papers at … Continue reading during the commemoration of the Columbian Quincentenary in Los Angeles, at a multimedia performance in October 1991.[59]Mondo Novo: A Multimedia Fairy Tale Around the Columbus Quincentennial, written and directed by Matt Silverstein, performed at Highways, Santa Monica, 4–6 and 11–13 Oct 1991. Promotional postcard … Continue reading We were introduced by my dear friend, the artist Ricardo Reyes. At the time, I had been exploring the life of conquistador-turned-Amerind-advocate Álvar Núñez Cabeza de Vaca, perhaps the first European to document Two-Spirit people in this New World.[60]My first encounter with Cabeza de Vaca was via Katz (1976, 285), later having been introduced by my mentor Charles Cameron to Haniel Long’s 1936 Interlinear to Cabeza de Vaca, a visionary fictional … Continue reading Telling Goldman of my interest, she replied that surely I knew of a major Quincentenary bibliography that had been published. Embarrassed but eager, I told her I didn’t. She gave me her card so I could follow up.[61]The bibliography contained the Spanish-language original of Cabeza de Vaca’s relación, which I obtained. Later that night my friend Ricardo told me of this daughter of Jewish Russian émigrés and her expertise in the field of Arte Chicano, the title of one of her books (Goldman 1985).

Shifra Meyers was born in New York in 1926 to restaurant server Abraham Meyerowitz of Russia and Sylvia (Kadish) Meyerowitz of Russia or Poland.[62]”California, County Marriages, 1850–1952,” database with images, FamilySearch (https://familysearch.org/ark:/61903/1:1:K8X4-M1T : 28 November 2014), Albert Goldman and Shifra Meyers, 05 … Continue reading She attended the High School of Music and Art in New York before moving to Los Angeles in the 1940s where she enrolled at UCLA as a studio art major, but left as an undergraduate, becoming involved with the Mexican American civil rights struggle of Bert Corona and Community Service Organization. Corona also worked with the more Red-friendly Asociación Nacional México-Americana (García 1994, 168), and by 1949, Meyers was administrative secretary of the Civil Rights Congress.[63]See the caption for a photograph: “Shifra Meyers holds wire copy about ‘New York 12’ trial, 1949, Los Angeles,” and its handwritten note on the verso, “Shifra Meyers – Adm Sec of Civil … Continue reading She lived in East L.A., learned Spanish, and had a son with John García in 1953,[64]Ancestry.com. California Birth Index, 1905–1995 [database on-line]. Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations Inc, 2005. Original data: State of California. California Birth Index, 1905–1995. … Continue reading but the two split sometime later. During this time, she worked at a kitchen appliance factory and later as a bookkeeper. In 1956, she married Arthur Goldman,[65]”California, County Marriages, 1850-1952,” database with images, FamilySearch (https://familysearch.org/ark:/61903/1:1:K8X4-M1T : 28 November 2014), Albert Goldman and Shifra Meyers, 05 … Continue reading divorcing later, but retaining his surname. She went back to UCLA and completed her bachelor’s degree in art in 1963, obtained her master’s from Cal State LA in 1966, and received her doctorate from UCLA in 1977, the latter two in art history. The reason for the eleven-year gap between MA and PhD: it took that long before a professor at UCLA would approve Goldman’s chosen dissertation on contemporary Mexican art, others having felt the art in question was derivative and overly political, and, thus, dismissible. This was the first step in a career of a self-described “activist art historian” who declared on the occasion of the Columbian Quincentenary, “We really have to rewrite the history of modern art. That’s the tall order that many of us have set for ourselves. You have to insert the modern art of Asia, Africa and Latin America.” The social challenges of East L.A. in which Goldman had been immersed in the 1950s were analogous to what she faced as an art historian in the coming decades. “Hierarchies, like those that separate classes and races on a social and economic basis,” wrote art critic Leah Ollman in her profile of Goldman, “are also deeply entrenched in the field of art history, placing the art of Western Europe, for instance, high above that of Latin America, or the art of men over that made by women.” Goldman’s son Eric García, reflecting on his mother, remarked, “She said she was a women’s libber before it existed. She had a hard time with men. They didn’t want this intellectual powerhouse. She was a very intense woman.” And so, this was the woman, known in 1952 as Shifra Meyers, with whom Harry Hay had had a telephone conversation that April regarding police entrapment at the Echo Park boathouse, precipitating his four-page rejoinder.

Comrades

Three years after Harry Hay’s conversation with Shifra Meyers, he appeared before a panel of the House Un-American Activities Committee, on July 2, 1955. The hearing transcript, barely three pages in length, contains Hay’s straightforward refusals to answer questions regarding his having been an instructor for, and member of, the Communist Party. During a moment of defiance in the hearing he referred to a previous witness as a “stoolpigeon.” (U.S. House 1955, 1873–1875) With no corroboration reflected in the transcript nor by the local press, nor even by Hay’s attorney, Hay claimed later that his non-cooperation so flustered HUAC counsel Frank Tavenner that he overturned “this huge oak desk on its face” and that the hearing transcriber’s “tight paper rolls” “sailed into the air.”[66]The first quote is taken from Katz (1976, 108), the second and third from Timmons (1990, 189). Despite Hay’s recollection, his attorney Frank Pestana characterized the hearing as being “short and … Continue reading Hay had feared the hearing would dwell on his involvement with the Mattachine as much as with the CP (Katz 1976, 106). When it did not, Hay appears to have tempered the anticlimax by inventing dramatic details for the hearing in compensation for his anxiety heading into it.[67]Hay’s trepidation was exacerbated by the fact that he’d been rebuffed in his search for an attorney who would counsel him in regard to his Mattachine involvement. “I was almost … Continue reading

Three and a half years after Hay’s HUAC appearance, Shifra Goldman also was questioned by a HUAC panel, on February 24, 1959. She was counseled by Esther Shandler who had been profiled that same year in HUAC’s report on Communist Legal Subversion, which claimed Shandler had been identified in 1952 HUAC hearings as “a member of a group of Communist lawyers in the Los Angeles area” and had appeared in those same hearings as an uncooperative witness. Shandler’s CP-oriented clients included the Los Angeles Committee for Protection of the Foreign Born. (U.S. House 1959a, 64)

Goldman, in response to HUAC counsel Frank Tavenner’s request that she provide her maiden name, replied, “Before I answer that question, I would like to inquire to the nature of this discussion here today,” which required Tavenner to read the several paragraphs of the resolution that mandated the Los Angeles hearing. Tavenner then asked Goldman for her maiden name once more. After several exchanges with Tavenner and with the panel’s chair, Goldman refused. As with Harry Hay, the panel’s only interrogation of substance pertained to her role as a Communist Party instructor—in a Shifra Goldman Study Group, which was a CP youth club whose members ranged in age from 17 to 30, and which had been conducted for at least the last couple of years. Goldman again refused to answer and was excused. (U.S. House 1959b, 274–278)

Vice and Venality

Two weeks after Harry Hay wrote Shifra Meyers in that April 1952 letter, he (again as Joseph Harrison) sent the Civil Rights Congress at least two items on behalf of the Citizens’ Committee to Outlaw Entrapment. One was a mimeographed invitation to attend the trial of Dale Jennings, then scheduled for Monday, May 19.[68]Harrison “Invitation,” n.d., but before 15 May 1952 (Civil Rights Congress 2:5). The invitation mentions a “letter hereby enclosed” and also the Committee’s “original ‘Anonymous Call to Arms’.” The enclosed letter (also from “Harrison”) was a mimeographed form letter with manually typewritten date (May 15) and addressee (CRC). (The letter’s original aim, according to an existing draft, was “to be sent to all city editors, and every columnist we can think of, as soon as possible.”[69]Harrison draft form letter, n.d. (Mattachine 2008 1:14). The draft was to be discussed “on Friday,” with no date noted.) The manually typed salutation—“Gentlemen:”—appears calculatedly insensitive in light of Hay’s previous communication with the female Meyers; the letter’s tone is of an introduction to the Citizens’ Committee to Outlaw Entrapment, and it lays out a single main argument in just over two pages, summarized by the Committee’s aim,

to expose to all eyes an injudicial and unconstitutional police conspiracy which, under the cloak of public morals, threatens not only all Minorities but civil rights and privileges generally. The pattern is simple and deadly. With full confidence in the gullibility of a community deliberately blinded by prejudice, the police “rig” a venal situation. The chances are six-to-one that the victim will offer to pay during the two hours it takes the prowl car to get to the nearest district station three miles away, a time-lapse known as the “sweat-out” period.[70]Harrison to Civil Rights Congress, 15 May 1952 (Civil Rights Congress 2:5).

This is what befell Dale Jennings, having been taken for a long, slow drive by his arresting officers. “It was a peculiarly effective type of grilling,” Jennings wrote later. “They laughed a lot amongst themselves[,] then, in a sudden silence, one would ask” a question. Jennings remained silent. “I sat on my hands and wondered what would happen each time I refused to answer. Yes, I was scared stiff. Then more laughter and shop talk and another sudden question. Some of them were about my work and pay.” (Jennings 1953, 12) A subtle suggestion of a solution….

The next-to-last paragraph of the Citizens’ Committee form letter punctuates the payoff, that “it would be ridiculous to assume that the police would allow so remunerative a racket to be exposed without some sort of a struggle,” followed by the last paragraph, which begins,

The Committee wishes it expressly understood that it is precisely this type of venality which it is determined to expose. We firmly believe that our purposes and objectives are in the best interest of our community’s welfare.

But then, with no segue, the missive takes a defensive turn, as if something was missing. Whereas the first sentence above talks of the Committee exposing the sweat-out scheme, the next sentence reads, “There are no lids to blow off.” Huh?

There are no lids to blow off. Our funds are accountable to the penny. Our hands are clean, our consciences clear, our eyes fixed firmly on the day when we will have restored to us the simple rights and privileges traditionally accorded to American Citizens generally.[71]These quotations are from Harrison to Civil Rights Congress, 15 May 1952.

There was something missing. The form letter sent to CRC is identical to the aforementioned draft, but contains gaps in the transition of page 2 to page 3. The missing bit:

Our Committee has been informed that a deputy-City-Prosecutor, who is himself a Homosexual, said to one of our supporters, “stay away from that Committee with a ten-foot pole. The police know all about it, and are just waiting to blow the lid off.”[72]This language is from the Harrison form letter’s draft version in Mattachine (2008 1:14). The complete draft version is reprinted in Cutler (1956, 22–25).

So, two months after columnist Paul Coates asked of the Mattachine treasurer, “Where Is Romayne?”, its Citizens’ Committee subsidiary was doing damage control regarding its own finances. And it narrowly avoided the possibility of precipitating an inquisition in the City Attorney’s office.[73]Curious as to the number of Deputy City Attorneys who might have been investigated in light of the Citizens’ Committee’s original draft, I did a high-level search of Los Angeles Times articles … Continue reading Rather than rewrite the form letter’s last two pages, Hay used correction fluid to mask the excised sentences, saving the time and effort of retyping, and a few cents for the mimeograph stencils, but garbling the message.[74]The Surplus Store in Gulfport, Mississippi sold stencils in 1950 at the rate of 24 for $0.98 (“Miscellaneous For Sale,” Daily Herald, 16 Oct 1950, 14).

A Single Minority

The Citizens’ Committee to Outlaw Entrapment message was mutated if not garbled in the weeks surrounding the Dale Jennings trial. On August 4, 1952, about two weeks after Jennings’s retrial was cancelled mid July, William Rubio, an entrapment target who had been shot at the Echo Park boathouse that January 27, was set for trial facing charges of assault with a deadly weapon and possibly attempting to aid a prisoner’s escape.[75]Clipping: “Frameup trial on Monday,” datelined 24 July 1952, source unknown; this clipping mentions only the weapons charge, but the “Fact Sheet – Echo Park Shooting” mentions that Rubio … Continue reading Yet, historian Emily K. Hobson (2014, 190) argues that by the time of the Jennings trial, the Mattachine “stopped mentioning the Echo Park case and more generally ceased to note links between practices of entrapment and brutality, the policing of gay life and the policing of communities of color.” It is remarkable that the two leaflets produced after Jennings’s trial—the first issued while a new July 23 trial still loomed, the second (dated July 19) after the City asked for dismissal—do not stress the fact that Jennings’s arresting officers were on trial at the same time he was—and for beating a Mexican American during a vag-lewd arrest![76]“An Open Letter to Friends of the Citizens’ Committee to Outlaw Entrapment,” n.d., but between about 02 Jul and 19 Jul 1952, states that Jennings’s arresting officer was “later tried for … Continue reading No longer was there language addressing the “police conspiracy” that “threatens not only all Minorities but civil rights and privileges generally,” as Hay had written in the May 15 form letter.

In the first of the July 1952 leaflets, “An Open Letter,” the Mattachine comes out of the closet: “Since we last communicated with you we have become affiliated with the Mattachine Foundation […].” And with that affiliation, the Citizens’ Committee propaganda moves from expansive and inclusive to more circumspect and parochial while appealing to allies: “This is a GREAT VICTORY for the homosexual minority and for all citizens interested in equal justice under the law.”[77]“An Open Letter to Friends of the Citizens’ Committee to Outlaw Entrapment.” The second leaflet, “Victory!”, offers more of the same: “Heterosexuals and homosexuals alike are potential victims of entrapment.”[78]“Victory!”, 19 Jul 1952 handwritten date (Mattachine 2008 1:14). A facsimile appears in Cutler (1956, 25). Both these leaflets are fundraising entreaties, and both, based on my reading, are in the compact style of Chuck Rowland rather than that of the verbose Harry Hay. But even the earlier, pretrial one-page flier “NOW is the time to fight”—laid out in the same style of staggered paragraph indentations as these later two leaflets—mentions the Echo Park boathouse case. Mattachine’s maneuver is not trivial. In “Policing LA: Mapping Racial Divides in the Homophile Era, 1950–1967,” Hobson devotes her entire essay to the subject. “‘Homophobic rhetoric and stepped-up policing’ have been ‘state tools for imposing racial norms,’ especially norms against interracial contact in public space,” Hobson writes (2014, 192), quoting queer theorist Lisa Duggan.[79]Lisa Duggan, “Down There: The Queer South and the Future of History Writing,” GLQ, Vol. 8, No. 3 (2002), 385. Hobson then provides a statistic published by LAPD: 2,430 “sex perversion” arrests in 1950—a nearly 85 percent increase over the yearly average in the 1940s. And with only ten percent of the city’s population, it was the city’s Central Division (downtown, Westlake, Echo Park, some of Silver Lake), as Hobson writes, that “experienced almost a quarter of all arrests, over a third of all vice arrests, 52.1 percent of sex perversion arrests, and 63.9 percent of arrests for prostitution.” Central Division “was largely working-class and the most racially mixed area of the city,” Hobson writes. By 1956, “white men were less likely, and black and Latino men twice as likely to be arrested for ‘sex offences’,” as sex perversion now was termed, “compared to their population.” (Hobson 2014, 199, 200) After the triumph of Dale Jennings the Mattachine appears to have been covering its (white) ass regarding its finances rather than allying itself with other minorities.

¶ For the next in this triad of articles see “Blown Cover: The Arrest of Dale Jennings” and “Queer Questionnaire and Coates Column.”

References

Abbreviations: CPUSA = Communist Party of the United States of America; FBI = Federal Bureau of Investigation; ONGLA = ONE National Gay and Lesbian Archives at the USC Libraries; SCL = Southern California Library for Social Studies and Research

Bettina Aptheker. 2015. Queer Dialectics/Feminist Interventions: Harry Hay and the Quest for a Revolutionary Politics. English Language Notes, Vol. 53, No. 1 (Spring/Summer), 11–22. I am grateful to Prof. Aptheker for providing me with this.

Barrett, Edward L. Jr. 1951. The Tenney Committee: Legislative Investigation of Subversive Activities in California. Ithaca: Cornell University Press.

Bernstein, Shana. 2011. Bridges of Reform: Interracial Civil Rights Activism in Twentieth-Century Los Angeles. New York: Oxford University Press.

Calif. Assembly. 1950. Preliminary Report of the Subcommittee on Sex Crimes of the Assembly Interim Committee on Judicial System and Judicial Process. Pagination as published in the Assembly Journal: 1950 First Extraordinary Session, 08 Mar 1950, 29–298.

——. 1952 (08 Aug 1952). Report of the Subcommittee on Sex Crimes of the Assembly Interim Committee on Judicial Systems and Judicial Processes. I cite this report in discussing the bills Harry Hay mentioned in his 28 Apr 1952 letter to Shifra Meyers but, of course, the report itself had not yet been issued.

Civil Rights Congress, Los Angeles. 1940s–1950s. Southern California Library for Social Studies and Research, MSS 016. Boxes and folders in my text are rendered, e.g., Civil Rights Congress 2:5. I am grateful to Michele Welsing (SCL) for providing me with a portion of 2:5.

CPUSA. 1938. The Constitution and By-laws of the Communist Party of the United States of America. New York: Workers Library Publishers.

——. 1940. The Constitution of the Communist Party of the United States of America. New York: Workers Library Publishers.

——. 1944. Constitution of the Communist Political Association. New York: Communist Political Association.

——. 1948. The Constitution of the Communist Party of the United States of America. New York: Workers Library Publishers.

——. 1957. Constitution of the Communist Party of the United States of America. New York: New Century Publishers.

Cutler, Marvin. 1956. Homosexuals Today 1956: A Handbook of Organizations & Publications. Los Angeles: Publications Division of ONE, Incorporated.

D’Emilio, John. 1970s. Correspondence: Chuck Rowland. Interview notes: James Gruber, Harry Hay, James Kepner, Dorr Legg, Konrad Stevens, as listed below. In the possession of D’Emilio as of July and August 2009, and March 2014. I am grateful to John D’Emilio for providing me with copies of these documents.

——. 1976. Notes from interview with Harry Hay, 16–19 Oct 1976, San Juan Pueblo, NM.

Eisenhower, Dwight D. 1953. Executive Order 10450: Security requirements for Government employment. Facsimile at National Archives Catalog, accessed 25 Jun 2016. Transcription at National Archives, accessed 26 Jun 2016.

FBI. 1953 (09 Sep 1953). Two documents: 1) H. Rawlins Overton. Report: The Mattachine Foundation, Inc. […], ONE, Inc. Los Angeles. Case No. LA 100-45888. Declassified 02 Apr 1985. 2) S[pecial] A[gent in] C[harge], Los Angeles, to Director, FBI. Office Memorandum: The Mattachine Foundation, Inc. […], ONE, Inc. Internal Security – C. Declassified 06 Feb 1984. The latter document is a cover memo for the former 52-page report. The versions posted on the FBI’s Vault website are redacted differently from that posted on GovernmentAttic.org.

——. 1954a (19 Feb 1954). Richard J. Nelson. Report: Charles Dennison Rowland. Los Angeles. Case No. LA 100-30913. Declassified 11 Aug 2009. Issued to David Hughes.

——. 1954b (23 Feb 1954). Louis K. De Geus. Report: Harry Hay. Los Angeles. Declassified 08 Sep 2010. Issued to Cliff Kincaid, America’s Survival Inc., http://www.usasurvival.org/home/marxism-n-america.html, accessed 14 Jun 2016. This iteration contains far fewer redactions than that accessed in Hay Papers 1:20.

——. 1954c (02 Mar 1954). [Author redacted]. Report: Robert Booth Hull. Los Angeles. Case No. LA 100-31390. Declassified 21 Jul 2009. Issued to David Hughes.

García, Mario T. 1989. Mexican Americans: Leadership, Ideology, and Identity, 1930–1960. New Haven: Yale University Press.

——. 1994. Memories of Chicano History: The Life and Narrative of Bert Corona. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Gernreich, Rudi. Rudi Gernreich Papers, Collection 1702, UCLA Special Collections, Charles E. Young Research Library, UCLA. Boxes and folders in my text are rendered, e.g., Gernreich Papers 58:9. When I accessed the papers on 30 Jan 2010, the collection was unprocessed, so my references are based on the finding aid, accessed 06 Apr 2015.

Goldman, Shifra M. and Tomás Ybarra-Frausto. 1985. Arte Chicano: A Comprehensive Annotated Bibliography of Chicano Art, 1965–1981. Berkeley: Chicano Studies Library Publications Unit, University of California.

Hay, Harry. Harry Hay Papers, GLC 44, Gay and Lesbian Center, San Francisco Public Library. Boxes and folders in my text are rendered, e.g., Hay Papers 11:36. I am grateful to Tim Wilson (SFPL) for providing me with the finding aid for this collection in 2009 before it was fully processed.

Hobson, Emily K. 2014. Policing Gay LA: Mapping Racial Divides in the Homophile Era, 1950–1967. In The Rising Tide of Color: Race, State Violence, and Radical Movements Across the Pacific, edited by Moon-Ho Jung. Seattle: Center for the Study of the Pacific Northwest in association with University of Washington Press.

Hurewitz, Daniel. 2007. Bohemian Los Angeles and the Making of Modern Politics. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Jennings, Dale. 1953. To Be Accused, Is To Be Guilty. ONE magazine. Vol. 1, No. 1 (January), 10–13.

Katz, Jonathan Ned. 1976. Gay American History. New York: Thomas Y. Crowell.

Mattachine. 2008. Mattachine Society Project Collection, Coll2008-016, ONGLA. Boxes and folders in my text are rendered, e.g., Mattachine 2008 1:20.

Timmons, Stuart. 1990. The Trouble with Harry Hay: Founder of the Modern Gay Movement. Boston: Alyson Publications.

U.S. House. 1955. Committee on Un-American Activities. Investigation of Communist Activities in the Los Angeles, Calif., Area (27 Jun through 2 Jul).

——. 1959a. Committee on Un-American Activities. Communist Legal Subversion: The Role of the Communist Lawyer (released 16 Feb 1959).

——. 1959b. Committee on Un-American Activities. The Southern California District of the Communist Party: Structure—Objectives—Leadership—Part 3 (24 and 25 Feb).

Text by David Hughes. © 2018 David Hughes. All rights reserved.