Blown Cover:

The Arrest of Dale Jennings

by David Hughes

Posted January 4, 2018

A Triad: Part II

1952 was a watershed year for the Mattachine. The organization had begun its engagement with the larger community by standing in solidarity with Mexican Americans who, like homosexuals, were targets of the Los Angeles Police Department. With the arrest of its cofounder Dale Jennings in March of that year, the Mattachine had a test case of its own to rally ’round, but in that effort the group turned inward rather than outward. I examine this dynamic in the first of three articles, “Harry Hay Meets His Match.” I also look toward the remarkable woman Hay met along the way.

The gamble to back Jennings paid off. His superb legal representation—bankrolled by Mattachine fundraising—resulted in a hung jury, allowing the organization to capitalize on an impossible dream: an admittedly homosexual man beating a charge of lewd vagrancy. The present article reviews some of the particulars of the case, including the identity of his arresting officers. I also examine LAPD’s liberal employment of the lewd vagrancy allegation as well as its use of a tactic known as the “third degree” and brutalization in general.

In the fall of 1952, emboldened by Jennings’s success in court, the Mattachine once again turned its gaze outward, this time to civic leaders and local candidates for office. The vehicle of outreach was a brief survey known to have been completed by only three or four respondents, but when it came to the attention of a local newspaper columnist, the concerns he voiced about the Mattachine turned out to reflect those already in the minds of its members, as discussed in “Queer Questionnaire and Coates Column.”

The following is adapted from my work-in-progress with the working title The Feeble Strength of One: Bob Hull, Chuck Rowland, Maxey, Marx and the Mattachine. Because its length likely would prevent its eventual publication as-is, I offer it here.

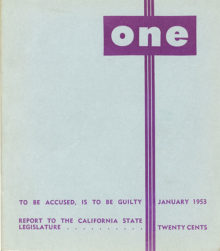

Solitary Man

In March of 1952, Mattachine cofounder Dale Jennings was arrested for lewd vagrancy, an all-too-common charge leveled against gay men. Goaded by fellow cofounder Harry Hay, Jennings’s decision to fight the charge would bring much attention to the Mattachine. Nine months after his arrest, he wrote a detailed account of the incident in the inaugural edition of ONE magazine, of which he would become editor. He prefaces his account with a lengthy admission that he expects no one to take him at his word regarding that evening’s events, “For to be accused is to be guilty.” To begin with, he’d not been on the prowl at all that night, but rather had been in search of a good motion picture. “Two movies that I passed were uninviting and, on the way to a third up the street, I was unwise enough to use a public rest room in a park” at about 9 p.m. Leaving, he was followed by a “big, rough looking character who appeared out of nowhere” and who tried to engage Jennings in conversation as they walked toward a third theater, showing a film he’d already seen. Turning home, and figuring the man might rob him, Jennings tried but failed to lose him. At Jennings’s door the man invited himself in, sprawling first on the divan, then on the bed, “making sexual gestures and proposals.” After Jennings repeatedly declined, the man “grabbed my hand and tried to force it down the front of his trousers. I jumped up and away. Then there was the badge and he was snapping the handcuffs on with the remark, ‘Maybe you’ll talk better with my partner outside’,” a partner who was not there. They walked back to the park, finding the partner and another officer. Placed in the back seat of a patrol car, the three cops grilled Jennings about being gay, about his job, laughing about their own work. Although he “expected the usual beating,” Jennings refused to answer. Eventually the car slowly moved “over a mile past Lincoln Heights then slowly doubled back. During this time, they repeatedly made jokes about police brutality, laughingly asked me if they’d been brutal and each of them instructed me to plead guilty and everything would be all right.” Jennings was booked at 11:30 but not allowed to make a phone call until 3 the next morning. At one point during the ordeal, Jennings “wondered how obvious I must have appeared” to the vice cop to cause his persistence, “until [the cop] remarked to another officer in the patrol car that things had been very dull this week. ‘It’s all I can do to keep up the old quota’.” (Jennings 1953)

Although much has been written about Jennings’s arrest, some details have remained murky or unexamined altogether such as the identity of the officers who arrested him, which I disclose below. Until only relatively recently was the night of his arrest identified as a Friday in March 1952. Harry Hay said it took place on a Saturday night (Tuchman 1987, 171) in February (D’Emilio 1976a). Absent that recollection, a date range could be inferred by Mattachine cofounder Rudi Gernreich’s spiral notebook of Mattachine meeting notes for 1952, which mentions an entrapment case for the first time on March 28; the previous meeting notes are for two weeks before (Gernreich Papers 112:1).

“I was the one [Jennings] called at two o’clock in the morning,” Hay recalled to oral historian Tuchman (1987, 171, 172). “I suppose he thought if anybody had money, I might, and it happened that at least I had a checkbook. So I went down and bailed him out early Sunday morning,” Hay said. “I […] got over there by three. The bail bondsman didn’t come before four-thirty, and then I had to wait at the old city jail for Dale to be released at six.” To his biographer, Hay recalled having cash on hand, and that Jennings was released by 6:30 that morning (Timmons 1990, 164).

Jennings’s arrest date was documented by the FBI via LAPD records. Although Jennings’s name is redacted in much of the Bureau’s Mattachine file,[1]Available on the FBI website via The Vault. its September 9, 1953 report containing the arrest date was parsed by historian Douglas M. Charles (2010, 266).[2]Charles writes (2010, 266 n10) that “Jennings has the dates of his arrest and trial wrong in his article” (Jennings 1953), but the article mentions no dates at all. Charles also states (266) that … Continue reading Buried in the middle of the report’s fifty-two pages, a précis of the case states that Jennings (name redacted but easily identified by his unredacted employer) was arrested “for violation of Section 647.5 of the Penal Code (Vagrancy – Lewd)” on Friday, March 21, 1952 (FBI 1953, 21).[3]C. Todd White (2009, 25) writes that Jennings stated he’d been accused of violating § 288a, but White omits the source. According to White (236 n26), this statute dealt with the crime of oral … Continue reading

After Jennings’s release the next morning, he and Hay had breakfast at the Brown Derby. “I wanted to hear the story firsthand,” Hay recalled. (Tuchman 1987, 171) Jennings’s story, as told by Hay to his biographer, doesn’t quite match the published version.

Dale had just broken off with Bob Hull and was not, I know, feeling very great. He told me that he had met someone in the can at Westlake Park. The man had his hand on his crotch, but Dale wasn’t interested. He said the man insisted on following him home, and almost pushed his way through the door. He asked for coffee, and when Dale went to get it, he saw the man moving the window blind, as if signaling to someone else. He got scared and started to say something, when there was a sudden pounding on the door, and Dale was arrested. (Timmons 1990, 164)

And Hay told a slightly different version to oral historian Mitch Tuchman.

Dale had been in a very despondent state at that time. He had recently broken up with a lover, had moved out, and had gotten himself a little apartment in the Westlake [now MacArthur] Park District [about two miles west of downtown], maybe a couple of blocks west of the park and maybe a block south. He had only been in the apartment a couple of weeks; none of us had seen it yet.

Anyway, […] he was accosted by someone, and it was obvious from the overtures that the guy was angling to be invited over to Dale’s apartment for sexual purposes. Dale didn’t like him. He mistrusted him, so he wanted to get away as quickly as possible. But the man wouldn’t be shaken […].

I’m not clear at this moment whether or not he managed to stick to Dale long enough so that as Dale went in the door he went in with him. But he had a partner, and I do know that his partner attempted to get in through the window. That’s it. I guess one of the men stayed with him, and the second person tried to get in the window—this was the “witness” situation—and presumably they arrested him at that moment. The whole thing was done under duress, and Dale was very upset about it and almost felt raped by the whole situation.

The “witness” would become key to Jennings’s defense, the witness being the arresting officer’s partner, who—having been signaled-to by blinds or not—was absent from the scene of the infraction. At least, this would be Jennings’s story, and one that would sway most of the jury at his trial. Continuing, Hay told Tuchman:

After he was apprehended, they put him in a car. They attempted first of all to be tough with him. Then they were sweet and solicitous. I don’t think that Dale was ever quite clear what he’d said and what he hadn’t said in the car. This is my remembrance of it. Anyway, they booked him.

I listened to Dale’s story, and I came to the conclusion—Dale was not in favor of this—that this was a perfect case to fight because it looked like a clear case of entrapment: Dale had been unwilling, reluctant all the way, and was still very reluctant and almost belligerent as he was talking to me at the Brown Derby. (Tuchman 1987, 171–172)

A Test(y) Case

No, Jennings was not in favor, as anthropologist C. Todd White explains in his study of the Mattachine and its offshoots, Pre-Gay L.A.: A Social History of the Movement for Homosexual Rights. White quotes from Jennings’s unpublished 1990 article, “The Trouble with Fairies,” in which he described how Hay threw his height around essentially to bully Jennings into agreeing to fight the charge against him.[4]Hay’s height is listed as 6 feet 2 inches in FBI (1952c). Jennings stood 5 feet 10 inches (FBI 1953, 21). Hay was

the only tall person I ever met who used it with the imperial self-confidence of the chosen…. From his great height, [Hay] laid heavy hands on my shoulders, stared intensely down at me in his best S.A.G. style, and made his great and solemn pitch. […] The Great Man pointed out that I, in my miserable way, would be somewhat Chosen, too, if I stood up to the Establishment. I had nothing to lose but my chains. After all, working in a family business, I couldn’t get fired. Being recently divorced,[5]Jennings’s third marriage was annulled 27 Sep 1950 (White 2009, 22), eighteen months prior to his 21 Mar 1952 arrest. it would not hurt my wife and I could continue at USC as something of a hero if the straights on campus didn’t go to work on me as they did all the fairies. He himself would be honored to do such a thing, but of course, he had too many familial responsibilities. Oh, I was lucky. (White 2009, 24)

Hay drove Jennings home and went home himself. Then he got to work.

At ten or eleven o’clock I started calling all the rest of the members of the steering committee, telling them what Dale’s situation was and that we should have a meeting that night because we were going to have to find an attorney for him. He was supposed to appear for arraignment Monday morning.

I think the meeting was held at Bob and Paul’s house in Echo Park.[6]Hull lived with Benard in the 1800 block of Preston Avenue. See Index to Register of Voters, Los Angeles City Precinct No. 1198, Los Angeles County, 1952 for Benard’s registration. The Registrar … Continue reading (Tuchman 1987, 172–173)

The choice of meeting venue is of interest, since Jennings’s ex-lovers Bob Hull and Paul Benard were said by Hay (as quoted in my profile of Benard) to have been conspiring in the Mattachine against Jennings prior to his arrest. Nevertheless, in the face of Hay’s argument for taking on Jennings’s case, “Rudi was in favor, and Paul was in favor,[7]The insertion of Benard’s surname and its misspelling are Tuchman’s. Benard’s assent at this stage of the discussion is significant. Hay, in his letter to Dorr Legg, 07 Jun 1956 (presumably ONE … Continue reading and Bob was in favor,” Hay said, “and Chuck [Rowland] made this great speech—it was beautifully done, very dramatic […].” (Tuchman 1987, 173) But the speech also turned comedic, Hay recalled to his biographer Stuart Timmons (1990, 165): “His eyes dark and blazing, Chuck said passionately, ‘The Hinger of Fistory points!’ There was a pause while everyone stared at each other. Rudi gasped and dissolved into uncontrollable laughter, and the rest of the group followed.”

Jim Gruber admitted to Timmons that he would often demur during discussions, but was unaware of any dissension in the group in this case (Timmons 1990, 165). “We were all in favor,” Hay recalled, “so therefore Dale, who was the victim in this case, finally decided that he was in favor too, but I think reluctantly so” (Tuchman 1987, 173). Again, any reluctance was lost on Jim Gruber. While Jim recalled Hay’s “eyes lighting up” upon “finding something we could pounce on and use,” according to John D’Emilio’s notes from Gruber’s interview (1976b), Jennings himself “ate it up.” In part echoing Jennings’s comments in “The Trouble with Fairies,” Gruber said that Jennings, having become “the chosen martyr,” “loved every minute of it.” Konrad Stevens concurred, at least regarding the opportunity: “We relished the thought and were almost glad it had come up” (D’Emilio 1977). Chuck Rowland agreed:

We had long pondered the “lewd and dissolute” label invariably attached to all gay arrestees. Would it be possible for an admittedly gay guy to be acquitted of a gay charge? We became positively obsessed with the idea. It would be our cause célèbre. We even toyed with the crazy notion of one of us going out and getting himself arrested just so we’d have our test case. Nothing came of that, because one night Dale […] was arrested “on suspicion of suspicion” by a real pig. This was our test case.[8]Rowland to D’Emilio, 17 Jan 1977 (D’Emilio 1970s).

Still they had to secure an attorney. Fred Snider, who apparently handled some legal matters for the Mattachine,[9]Timmons (1990, 165) writes that, at the time of Jennings’s March 1952 arrest, Snider had been “the attorney who handled the Mattachine Foundation’s incorporation,” but the Foundation was not … Continue reading could not take on the case, but gave them counsel regarding Monday’s arraignment. Per Hay:

We didn’t get hold of Fred Snider till evening, and he said there were two or three ways Dale could go. He could plead guilty to a lesser charge like lewd behavior or misconduct or something of the sort, and he would still have to register as a sex offender, but he probably wouldn’t get a jail sentence. He would be given probation. Or he could fight the whole thing all the way: plead not guilty and demand a jury trial.

This, as a matter of fact, is what he did. (Tuchman 1987, 173)

Penetration

Because Snider was too busy to take Jennings’s case, Hay thought of George Shibley, an attorney in Long Beach, who agreed (Tuchman 1987, 174; Timmons 1990, 165). Shibley had represented several of the defendants in the Sleepy Lagoon case of the early 1940s in which twenty-four men, all but one Mexican Americans, had been indicted for a murder. “By today’s standards, the trial was patently unfair,” a profile of Shibley reads, “defendants were severely restricted from conferring with their attorneys and denied clean clothing and haircuts until late in the trial.”[10]“Close-up: George Shibley Has Given Many an Underdog His Day in Court,” Los Angeles Times, 16 Jan 1986, 2. The summer of 1950, when Hay and Gernreich had circulated their World Peace Appeal petition at Bitches Beach,[11]In his 04 Jan 1977 letter to John D’Emilio (1970s) Chuck Rowland uses this nickname for the stretch of beach in Santa Monica, frequented by gay men, as being canvassed by Hay and Gernreich. Hay … Continue reading Shibley had defended two women for doing the same thing; disturbing the peace was the charge after they had been “too insistent” in their efforts and were threatened by a mob of 200.[12]“Women Jailed in ‘Peace Petition’ Circulation,” Los Angeles Times, 17 Jul 1950, 15; “Peace Petition Case Arraignment Put Off by Court,” Los Angeles Times, 18 Jul 1950, A8.

Eventually Shibley and two other attorneys would appeal the death sentence of Sirhan Sirhan, who was convicted of killing Robert F. Kennedy.[13]“Sirhan Retains 3 New Lawyers in Life Fight,” Los Angeles Times, 03 Jul 1969, B2. Shibley also said he’d known Charles Manson[14]“News Media Have Killed Me: Manson,” Chicago Tribune, 23 Dec 1969, A14, in which Shibley is quoted as saying that “I have known him [Manson] for several years.” since 1957[15]“Manson Wants to Defend Self,” Washington Post, 23 Dec 1969, A3, which states that Shibley “said he he had been a friend of Manson’s since 1957.” and hoped to “assist” him when he was charged with multiple murders in 1969,[16]“Manson Accepts Temporary Lawyer,” Los Angeles Times, 23 Dec 1969, 1, in which Shibley is described as one of “three attorneys who had hoped to be allowed to assist Manson in his defense.” … Continue reading although Shibley later denied wanting to “represent” Manson, claiming, “The crime was too horrible.”[17]“George Shibley Has Given Many an Underdog His Day in Court.”

Shibley was the son of Syrian Christian immigrants[18]Shibley and his brother were “of Syrian descent, their parents having been born in the Near East,” as reported in “Two Brothers Lead Orators,” Los Angeles Times, 07 Apr 1927, A8. U.S. Census … Continue reading and even at 75 was said to have had “penetrating brown eyes.”[19]“George Shibley Has Given Many an Underdog His Day in Court,” which states that Shibley’s parents were from Lebanon as well as that Shibley considered himself to be a “Christian socialist.” In his early forties at the time of the Jennings case, Shibley was recalled by Hay as coming “from an Armenian family,” being middle height, having blue-black hair, skin “originally white and pink in tendency” but now “bronzed and dark,” with eyes “open and glowing, sort of riveting in a way but with enormous pools of kindness in them.” The attorney was genuinely interested and concerned in the people he assisted. He “leaned across the desk and embraced you with his voice and his eyes,” Hay said. “He wasn’t sophisticated or sedate or withdrawn in any way. He was very much involved with his people.” But he’d have to become even more involved, admitting he needed to be educated about homosexuality, knowing nothing about it. (Tuchman 1987, 175, 173)

Thus began a series of sessions with one or two carloads of Mattachines gathering in Long Beach for dinner and then on to Shibley’s office to meet from eight to eleven. “Rudi went, because Rudi went with me,” Hay recalled. “Bob and Chuck and Dale were there and Paul, although I’m not sure that Paul always went because he was a TV writer and sometime TV producer […]. Sometimes Jim and Steve [Konrad Stevens] were there but not always.” These sessions—“educat[ing] George Shibley on what it’s like to grow up gay”—were extensions of the Mattachine discussion groups rather than replications; much of the present soul-searching simply had not arisen with all of these particular participants present, since, for about a year, each had been facilitating his own, disparate discussion groups. (Tuchman 1987, 175–178)

Just as the leaders of the Mattachine had found the early discussion groups instructive, their new revelations to themselves led to insights that were incorporated in what would become a new wave of Mattachine propaganda. This had to be discreet yet provocative enough to intrigue, respectable and somehow reassuring, since the threat of entrapment, at least in the psyche of Mattachine’s demographic, lay not only in bus station waiting rooms and public lavatories but also in living rooms devoted to discussions of illegalities.

Accustomed to being outlawed, the leaders did what came naturally: they created a front group to rally support for Jennings—the Citizens’ Committee to Outlaw Entrapment. One leaflet issued by the Committee asked, “Are You Spiritually Left-Handed?”—discussing the perceived perversity of those who “run against the grain,” as Hay put it.[20]Timmons (1990, 166) writes that the title was “Are You Left-Handed?” and it “compared homosexuality to any other inborn trait.” Such literature was distributed, according to Hay, in streetcars, bus stops, restrooms, gift and art shops, galleries, libraries, churches (!), and anywhere else “where there would be tables and stacks of literature around” (Tuchman 1987, 178–179). The Committee also issued the practical, fourteen-point handout, “Your Rights in Case of Arrest” (Hay 1996, 135–136).[21]A second versions of this handout omits the Q&As of point 3 and all of point 4, “Deny all accusatory statements by arresting officers […].” Both version are found in Mattachine (2008 1:14). Other handouts published by the group are discussed below.

Non gratis

George Shibley did not represent Jennings pro bono. “Shibley said that the cost of Dale’s trial, the cost of the trial and his fee, would come to about $750,” Hay recalled. Trial transcripts, at $75 apiece, could be useful for other attorneys. “We figured that maybe we would have ten transcripts made and that we would send them to other parts of the country.” (Tuchman 1987, 184) Hay’s biographer Timmons (1990, 167) writes that forty transcripts were anticipated. Indeed, Rudi Gernreich’s meeting notes for April 9 state a fundraising goal of $3,000 (Gernreich Papers 112:1). Hay told historian John D’Emilio about an “ingenious campaign” consisting of leafleting, making the Jennings case the main topic of the discussion groups, and fundraising. According to Gernreich’s meeting notes, as early as February 29, a Feast of Fools celebration already had been scheduled for the last weekend in March—a sort of Mattachine anniversary at which, Hay told D’Emilio, the Jennings case could be brought up in the “context of brotherhood, fellowship.” (At least some, if not all, of the Feast of Fools fête was cancelled, per Gernreich’s March 28 notes.) Raffles and small-scale fundraising parties were planned as well as two major events. (D’Emilio 1976a; Gernreich Papers 112:1)

Gernreich’s notes for that April 9 meeting mention a 500-ticket raffle and a party to be held May 3 (Gernreich Papers 112:1). It’s likely this event was what Timmons (1990, 167) called “a dance and raffle at the house of Jack Dye, a Mattachine member who lived with his wealthy mother at a secluded canyon estate in Trancas,” just north of Zuma Beach in Malibu.

Hay recalled nearly five hundred people attending, including “Jimmy [sic] Shields,” lover of actor-turned-interior-designer William Haines, who is said to have left the studio system in 1933 when he was asked to marry a woman. Shields himself in the 1930s had been known to act out at many a party. “More than one embarrassed host or hostess had to apologize to a handsome young actor or soldier who’d been the recipient of an unwanted grope from Jimmie” (Mann 1998, 212–215, 294).

At the time of the Mattachine party, Shields was three weeks shy of his forty-seventh birthday, having arrived with a large party of his own, “a bevy of, let’s say, beauties in various stages of decay,” as Hay put it (Mann 1998, 99; Timmons 1990, 167), having himself turned 40 a month before the party. Although the fundraiser’s proceeds might seem meager today, the event netted the cause $1,000 and then some, more than enough to cover Jennings’s legal costs (Timmons 1990, 167).

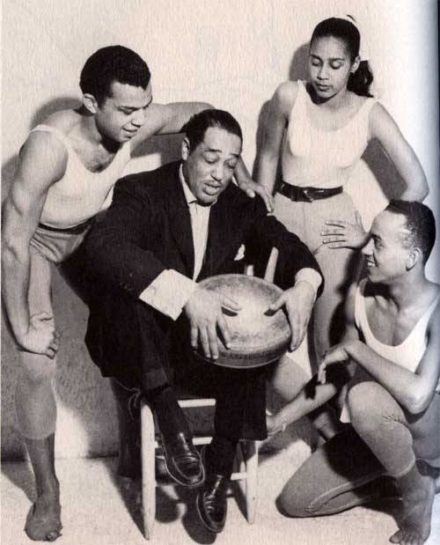

A second major fundraiser is mentioned in Gernreich’s April 23 meeting notes: a benefit dance performance scheduled for May 16 (Gernreich Papers 112:1).

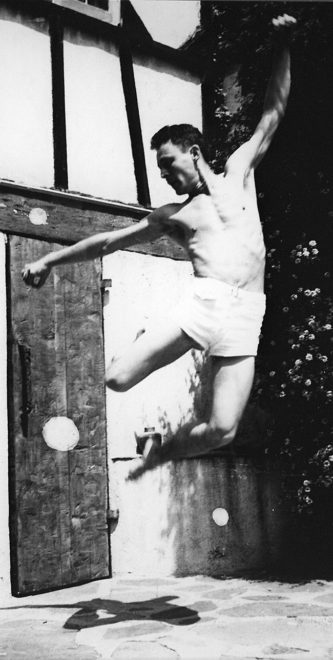

Timmons (1990, 167) writes that

Lester Horton offered an evening’s take from his current dance program. One of his own dancers had been entrapped that year, and Horton was in full sympathy with the daring campaign. Though the May 23 performance of three of his popular pieces was not advertised as a Mattachine benefit, most of those attending knew that it was, and the house was nearly sold out. Harry always credited Horton with sponsoring what was likely the first fund-raiser for a gay civil rights cause.

Newspapers billed the May 23 event as the “gala” opening night of Horton’s fifth season, a program that did not feature “three of his popular pieces” but rather the debut of three new productions, including adaptations of Duke Ellington’s Liberian Suite and Federico García Lorca’s play Yerma.[22]“Lester Horton Dancers in ‘Choreo’ May 23,” Los Angeles Sentinel, 08 May 1952, B2; “‘Choreo ’52’ to Present New Ballets,” Los Angeles Times, 18 May 1952, E5. Given the surplus of a Mattachine contingent attending Horton’s opening night, why wouldn’t the gala have sold out? In light of this, the May 16 performance date recorded by Gernreich should be considered. While a performance that night might have stretched the capacity of Horton’s company just a week before its season premiere, a program of Horton’s standard repertory might have been feasible.

Setting aside the actual date of the performance, the May 7 notes recorded by Gernreich read: “Fund drive $46.00 turned in. Reaction to Horton tickets mild. Guy mentions reaction by people to literature—Communist propaganda. Moderation and explanation by Second Order.” (Gernreich Papers 112:1) Also in May, Hay recalled that “in the middle of the [Mattachine] fund campaigns” Paul Benard, who at some point opposed the Jennings campaign, “panicked off to Mexico.”[23]Hay to Legg, 07 Jun 1956 (presumably ONE 2011 27:Hay). I was provided a copy of this letter when the cited collection was being processed. I include this incident in my profile of Benard. Hay scheduled his own private fundraiser for Friday, June 13 at which he’d play some “exciting but little-known recordings,” proceeds from which would go to the purchase of a mimeograph printer; donation: $1.00.[24]Hay mimeographed fundraiser letter, 04 Jun 1952 (Mattachine 2008 1:14). In the end, the Citizens’ Committee fundraising brought in only half of its $3,000 goal—still enough to defend Jennings and purchase ten trial transcripts, writes Timmons (1990, 167).

A post-trial missive to supporters was less rosy. While pledges were generous during the initial drive, they unfortunately exceeded the cash contributions by more than $2,000. A final audit of the Committee’s funds as of the end of June showed $2,913 pledged but only $860.96 actually collected.[25]“An Open Letter to Friends of the Citizens’ Committee to Outlaw Entrapment,” undated but issued prior to 23 Jul 1952 (Mattachine 2008 1:14).

Sui generis

Just as there was some confusion regarding the date of Jennings’s arrest, there is slight variance regarding the date of his trial. There appear to have been at least two continuances.[26]“Invitation,” issued by the Citizens’ Committee to Outlaw Entrapment, gives the trial date as 19 May 1952 (Civil Rights Congress 2:5), but it took place later, discussed below. In his letter to … Continue reading And the local press doesn’t seem to be of help in this regard. C. Todd White, writes (2009, 27) that “newspapers did little to cover the trial,” without providing an example of even scanty reportage. Edward Alwood (1996, 28) interviewed Jennings, who said that Harry Hay dangled the carrot of prospective press coverage during their Brown Derby breakfast, but “the papers ignored us,” Jennings said. Historian Jonathan Katz writes (1976, 415) that Hay recalled that not one media representative attended the trial. “We notified every journal [and] newspaper that we knew about, radio stations and TV stations, such as they were, and no one ever printed a line,” Hay told Tuchman (1987, 184), adding, “It was a total conspiracy of silence, a total blackout, except what we were printing.”

A post-trial leaflet issued by the Citizens’ Committee leads off, “You didn’t see it in the papers, but it could—and did—happen in L.A.”[27]“Victory!” leaflet, handwritten date 19 Jul 1952 (Mattachine 2008 1:14). Katz (1976) dates the leaflet to July 1952 in his text (415) but then questions the month (inserting a question mark) in … Continue reading

Historian John D’Emilio (1983, 71 n31) gives the trial’s opening as Monday, June 23, 1952, based on a letter Hay wrote on the subject that October.[28]Hay to Clark, 06 Oct 1952. But the same FBI report that dates Jennings’s arrest also contains the following: “[3-character redaction] advised that [Jennings] went to trial on July 23, 1952, in Division 26 of Municipal Court before Judge HUNT […]” (FBI 1953, 21). ‘July’ in the report is a typographical error, as confirmed below.

A few months after the trial, Jennings (1953, 13) described it as being “a surprise.”

The attorney […] made a brilliant opening statement to the jury in which he pointed out that homosexuality and lasciviousness are not identical after stating that his client was admittedly homosexual, that no fine line separates the variations of sexual inclinations and the only true pervert in court room was the arresting officer. He asked, however, that the jury feel no prejudice merely because I’d been arrested: these two officers weren’t necessarily guilty of the charges of beating another prisoner merely because they were so accused; it would take a trial to do that and theirs was coming the next day.

That this last statement was allowed to stand without objection, even in an opening statement, is not recorded. The two officers mentioned by Shibley actually were tried beginning on June 24, as discussed below, so the FBI report cited above is in error, off by a month.

Jennings’s attorney Shibley called the officers—arresting and witnessing—to the stand, but their testimonies contradicted each other and/or their depositions. In his obituary for Jennings, Paul Herrera writes, “Shibley pointed out that the arresting officer’s story was inconsistent with that of the witness […].”[29]“Remembering a Pioneer,” New Times Los Angeles, 22–28 Jun 2000, 16–17. Regarding the “witness,” Jennings writes (1953, 12) that this individual—the arresting officer’s partner—was not on the scene: “We walked all the way back to the park before finding him.” Chuck Rowland recalled:

You know, when an arrest is made, there have to be two policemen present. There was no second person present. Dale never saw a second policeman, until he was actually taken to the police car and taken down to the police station. Then there was another guy in it, who had been parked in the police car four blocks away or something, who hadn’t been a part of this at all. (Mattachine 1986)

In the trial, according to Hay, after leading one of the officers “up the garden path” in testimony, Shibley said, “Well, that’s very interesting because in your deposition you say exactly the opposite,” effectively impeaching him (Tuchman 1987, 182).

Shibley’s closing argument brought tears in the courtroom at least twice. He actually compared his own life as a Syrian American with the life of a homosexual: “the alienation, loneliness, being different, fears, courage,” Hay recalled in 1976, as recorded in John D’Emilio’s notes. Shibley’s own alienation, he told the court, ended at last in college, but there is no such respite for the homosexual, he said. “Wet eyes in the courtroom,” D’Emilio wrote. (D’Emilio 1976a) Hay’s 1987 remembrance of Shibley’s summation was complementary: that Jennings was homosexual, but he also was decent, honest, of high integrity, “and he’s as good as his word, and the man who has been appearing against him is a perjurer, as you have just heard […].” Upon hearing Shibley say this, Hay recalled, “We all […] just wept because nobody had ever said positive things about a gay person openly in a court of law in the United States up until that time.”[30]Timmons (1990, 168) writes, “Jim Kepner was told that similar cases were successfully fought around the same time, but the Jennings case was unique as a deliberately cooperative gay civil rights … Continue reading The prosecution’s case was “open and shut,” Hay said, portraying Jennings as “a naked pervert who had lured an unsuspecting officer into a trap” rather than the other way around. (Tuchman 1987, 182) The jury—all but one—didn’t buy it.

Jury deliberations took forty hours, according to Jennings (1953, 13). An FBI report (FBI 1953, 21), based on an informant’s statement a year later, claimed the jury deliberated for only two days. Hay wrote in his October 1952 letter that Jennings’s case “was argued for three days” and the jury took thirty-six hours “to bring in a hung verdict of 11–1 for acquittal. (11–1 was the count of the very first ballot,—and it never changed throughout the entire closeting. The bastard of the ballad was the Foreman himself.)”[31]See Hay to Clark, 06 Oct 1952. According to White (2002, 87), the trial lasted ten days, which likely included the jury’s deliberations. Following the trial, the Citizens’ Committee to Outlaw Entrapment sent its mailing list an open letter, first stating that “we have become affiliated with the Mattachine Foundation, a non-profit corporation, interested in the problems of sexual variance.” The Foundation would not be incorporated, however, for nearly ten months, a fact that would come back to haunt the Mattachine when it finally did get some press in 1953. The open letter summarized the trial, calling it a “great victory for the homosexual minority” and for all interested in equal justice. “But the victory is only partial, for a new trial is set for July 23rd.”[32]“An Open Letter to Friends of the Citizens’ Committee to Outlaw Entrapment,” undated but issued prior to 23 Jul 1953 (Mattachine 2008 1:14).

“Later the city moved for dismissal of the case and it was granted,” as Jennings writes (1953, 13).[33]In his 06 Oct 1952 letter to Clark, Hay wrote, “Twenty-three days later” after the end of the Jennings trial, and “five days before the case was scheduled to be re-tried,—The City moved to … Continue reading “The officers, in their trial” on brutality charges, “were found innocent although one was later suspended by the Chief of Police for the same charges.” But the Los Angeles Times reported that both officers were suspended, as discussed below. Its coverage provides details regarding these officers in particular as well as the trend of police brutality that actually had provoked the Mattachine in its biweekly meeting exactly a week before Jennings’s arrest.

Cover Blown

Beatings at the hands of the LAPD were being addressed by stakeholders in Los Angeles before, during, and after Jennings’s trial. Jennings’s arresting officers themselves were brought up on charges of brutality (unrelated to his case). As Jennings’s attorney George Shibley stated above, the officers were tried beginning on Tuesday, June 24, 1952, the day after Jennings’s trial had begun.

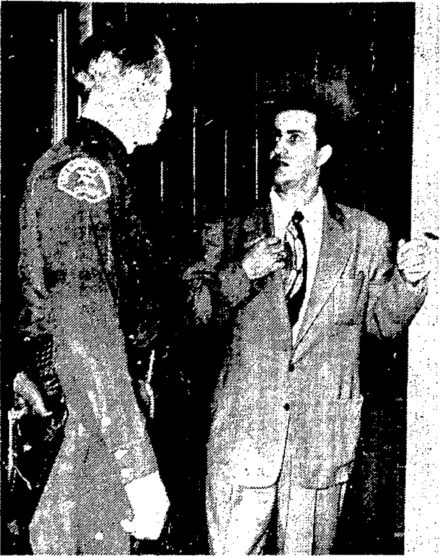

The two, James L. Martin and T. N. Porter, were members of the Central Division’s vagrancy squad.[34]Hobson (2014, 210 n60) gives Central’s boundaries in 1950 as east to Los Angeles River, west to Vermont Ave., north to Los Feliz Bl., and south to Pico Bl., later enlarged west to Hoover St. and … Continue reading According to the Los Angeles Times, they originally had been suspended April 8 “after the police internal affairs division reported it found evidence the officers had beaten a prisoner” named Ramón Castellanos.[35]“Chief Suspends Two in Brutality Quiz,” Los Angeles Times, 09 Apr 1952, 2. As reported in the Times, the prisoner “said that he was struck several times with fists and elbows as well as a ‘dark object,’ the injuries being listed as scalp and head lacerations which required 12 sutures to close, a black eye, a bashed nose and numerous bruises.” Martin and Porter “contended he was injured by stumbling into a large flower pot.”[36]“Two Officers to Face Beating Trial,” Los Angeles Times, 24 Apr 1952, 2.

Although the two officers were acquitted by a jury in their criminal trial on June 27, the police board of rights found them guilty on July 1 “of using undue force in making an arrest and making false reports to a superior officer […].” Martin’s and Porter’s penalties were a thirty- and ninety-day suspension, respectively, without pay.[37]“Policemen Found Guilty of Using ‘Undue Force’,” Los Angeles Times, 02 Jul 1952, A3.

Any cover these vice cops had was blown by their photographs in three of eight Los Angeles Times articles on the Castellanos case, and they made quite a team. Martin, who was broad shouldered, face fleshy with full lips, lived up to Jennings’s recollection nearly fifty years later: “good looking, big, muscular” (Slade 2001, 18). Somewhat rough, if not rough trade, one can imagine Martin telling Jennings he’d been in the Navy and that “all us guys played around,” as Jennings wrote at the time (1953, 12). Porter, on the other hand, was about eye-level with Martin’s chin, and I’m reminded of Bob Hull, who stood seven inches shorter than Chuck Rowland.[38]Hull’s height of 5 feet 6 inches, is recorded in FBI (1952a, 12); Rowland’s height of 6 feet 1 inch, is in FBI (1952b, 2). Jennings stood 5 feet 10 inches (FBI 1953, 21). The newspaper photographs elicit other comparisons as well: Porter, with his pencil mustache, recalls a somewhat anachronistic William Powell (star of The Thin Man and its sequels from the 1930s and ’40s) to Martin’s hunky Marlon Brando (who lost the Best Actor Oscar for Streetcar Named Desire that year to African Queen’s Humphrey Bogart).

A Pattern Emerges

The proceedings against vice officers Martin and Porter took place in the shadow of an ongoing investigation of LAPD brutality. So absorbed was the local grand jury with that inquiry that it refused to consider Martin and Porter’s case, leaving it to the police internal affairs division, which recommended the officers’ suspension on April 8, 1952.[39]See “Chief Suspends Two in Brutality Quiz.” But investigation of brutality wasn’t conducted only by the grand jury or by internal affairs.

On March 13 the FBI announced it had begun its own review of the matter, more than a week before. Allegations of police viciousness that had been raised in the notorious “Bloody Christmas” trial earlier that month—a trial of civilians (officers were yet to be indicted)—had emboldened others to come forward. Complaints of “numerous” civil rights violations had been lodged with the Bureau’s Los Angeles office, as reported by the Los Angeles Times, which also had learned that LAPD’s “own investigation implicated 16 officers directly with using brutality and 20 to 25 others indirectly.” The Times went on to list mixed statistics from the year before: 17 officers had resigned (none for brutality) rather than face its internal tribunal known as the police board of rights; 848 complaints of brutality etc. had been received, with 298 of those “being sustained and punitive action was taken.” Out of ten prosecutions by the board of rights, only two were found guilty resulting in termination; five obtained suspensions of an average of 39 days and two received reprimands. One of the ten was deemed not guilty.[40]“FBI Probing L.A. Police Brutality,” Los Angeles Times, 14 Mar 1952, 2. As this record demonstrates, the grand jury did not intervene. The Mattachine was well aware of LAPD behavior, as I discuss in this companion article.

The day Dale Jennings had his Brown Derby discussion of strategy with Harry Hay, on March 22, 1952, the Times wrote about “predicted” Bloody Christmas indictments—of police this time—but characterized those indictments as an anomaly: aside from one instance in 1943, “there is no modern record of a Los Angeles County grand jury indicting a police officer on brutality charges.”[41]“Brutality Indictment of Policemen Predicted,” Los Angeles Times, 22 Mar 1952, 1. This is incorrect, however, according to the Times’ own reporting: in 1943, officers were indicted for two separate instances of brutality occurring on December 19, 1942.[42]“Policemen Indicted in Brutality Case [sic],” Los Angeles Times, 04 Mar 1943, 1. The ‘case’ in the headline refers to brutalization of two jail inmates in separate incidents. Prior to that, in 1931 and 1932, two others had been indicted,[43]“Officer Posts Bail on Boy’s Accusations,” Los Angeles Times, 21 Oct 1931, A15; “Grand Jurors Rebuke Police,” Los Angeles Times, 04 Mar 1932, A1. out of a batch of ten cases the panel considered,[44]“Policy and Brutality,” Los Angeles Times, 05 Mar 1932, A4. winnowed from dozens of brutality investigations.[45]For instance, twenty-eight “additional” cases of brutality were to be placed before the grand jury on 21 Sep 1931, but in the end, only ten were heard. See “More Cases of Cruelty to Be … Continue reading Three more were indicted in 1948.[46]“Three Officers to Face Charge of Brutality,” Los Angeles Times, 17 Nov 1948, 2. While the grand jury generally was loath to indict cops for brutality, LAPD’s internal tribunal brought charges against several officers between the years of 1900 and 1952.[47]Curious about the seeming reluctance of the Los Angeles County Grand Jury to return indictments against police officers, and its parallels in 2013 that precipitated the Black Lives Matter movement … Continue reading Otherwise, in addition to officer resignations, it was constabulary, judicial, and civil actions, rather than those of the grand jury, that were brought to bear against the police, as documented in the Los Angeles Times and to a much lesser degree in the Los Angeles Sentinel, which served the Black community beginning in 1933.[48]“About,” Los Angeles Sentinel website.

Vag-Lewd: It’s Not Just for Queers

Three years before Dale Jennings was tried for lewd vagrancy the same charge was made against a jazz musician who had worked with Benny Goodman and whose “Tar Paper Stomp” was mined for Glenn Miller’s chart-topper “In the Mood.” The 1949 case of Wingy Manone demonstrated the lengths to which the LAPD vice squad would go. Joseph Manone was a trumpet player, composer, singer, bandleader, actor, and radio star. A native of New Orleans, he lost an arm in a streetcar accident at age ten, earning him the nickname “Wingy.” Seven months before his June 10, 1949 arrest on morals charges, Doubleday published his autobiography Trumpet on the Wing, including a foreword by Bing Crosby with whom he’d collaborated in radio and film.[49]“Loss of Arm Didn’t Keep Jazz Trumpeter from ‘Swing Street’,” Los Angeles Times, 26 Jun 1982, B16; “Jazz Characters Trumpet Their Lives,” Los Angeles Times, 14 Nov 1948, D4.

Manone was arrested in the heart of Hollywood on North Ivar Street at the apartment of two women who had invited him “for a little early morning sociability,” according to the Los Angeles Times. Manone, 49, was spied horsing around with Jean Phillips and Wanda Vermillion, both 24, by peeping vice-squadders James Parslow and T. C. Lindholm. The three cavorters “all were unclad,” the cops claimed. “But by the time they broke down the door, all were clothed and indignant at the intrusion.” They were arrested and booked on a charge of “resorting.” Police said Manone had given them “an awful tussle,” with Manone saying that they beat him without cause. “We didn’t know just what to do,” said Parslow. “You can’t handcuff a one-armed man.”[50]“Trumpeter Wingy Manone, Two Women Jailed on Morals Charge,” Los Angeles Times, 11 Jun 1949, 2. At trial in August, Municipal Judge Joe Waycraft found Manone and Vermillion guilty of resorting and lewd vagrancy, finding Phillips guilty only of vagrancy.[51]“Morals Charge Convicts Wingy,” Los Angeles Times, 11 Aug 1949, 11. In the article, Manone’s age is given as 38, but he was born 13 Feb 1900, according to his gravestone. Manone’s penalty, issued August 24, was a fine of $150 and two years’ probation. His probation report included testaments to his “character and standing from several wellknown persons, including Larry Crosby, a brother of the crooner.”[52]“Manone Gets Fined $150 and Probation,” Los Angeles Times, 25 Aug 1949, A2.

Vagrancy and the Third Degree

It would be of interest to members of the Mattachine, who were concerned with police brutality in that spring of 1952, that the term third degree had Masonic origins, given that the Mattachine itself was modeled to a certain extent on the Masons’ organizational hierarchy. The third degree “derives from the name which the Freemasons give to one of their orders […],” as explained by the New York Times. “To pass from the first degree to the second a Freemason must undergo an initiation, originally an examination, the ‘horrors’ of which he is bound to keep secret […]. The third degree [is] the most difficult to attain; initiation to it is correspondingly severe.”[53]“Police ‘Third Degree’ a Term Understood in All Countries,” New York Times, 30 Aug 1931, XX8. On the same page appears a sort of exposé regarding the ambivalence surrounding Pyotr Ilyich … Continue reading By contrast, the Mattachine initiation by candlelight described by Timmons (1990, 155) was anything but horrific. Cutler (1956, 12, 15) writes of an invitation to join the Mattachine followed by a cross-examination “with considerable care as to […] general attitudes and conduct,” with the successful inductee taking part in a “simple, yet reasonably impressive ceremony” that included recitation of a pledge to respect Mattachine interests as well as those of other minorities, to maintain social decorum, and to promote the group while maintaining anonymity.

The third degree had been examined twenty years before by the Wickersham Commission, appointed by President Hoover “to study the failures of law enforcement and shortcomings of judicial procedure,” vis-à-vis Prohibition, “which is likely to be the question upon which public interest will centre in the inquiry,” as the New York Times reported at the time.[54]“Hoover Names 10 Lawyers and One Woman Educator to Study Law Enforcement,” New York Times, 21 May 1929, 1. The Commission’s Report No. 11, on Lawlessness in Law Enforcement, issued August 10, 1931, essentially indicted the “third degree” methods of the LAPD, which consisted of delays in producing an arrestee during which information extraction was performed. Dale Jennings, in his slow drive to the station, experienced a “lite” version of the third degree. Report No. 11 read in part, “Despite the statutory provisions [to be followed by police], the third degree does exist in Los Angeles,” as quoted from the report by the Los Angeles Times.[55]“Los Angeles Police Hit.” Los Angeles Times, 11 Aug 1931, 1.

Before addressing the third degree, Wickersham Report No. 11 reviewed the practice of “changed charges,” i.e., large numbers of suspects picked up on a given charge that either was dropped or was swapped for another.[56]I’m compelled to remark here that at a meeting I attended of activists in Denver on 29 Sep 2015, this same practice was noted on the part of the local police. For the last two years of the 1920s, LAPD published statistics for this practice, fodder for the Wickersham probe. “Noteworthy are the large number of vagrancy charges,” Report No. 11 reads, “which are usually a pretext for arrest and have no relation to the charge, if any, on which the prisoner is subsequently held.” Of course, vagrancy—coupled with lewd conduct—actually was the charge whereby gay men were arrested by the vice squad in Los Angeles.[57]For instance, on 21 Jan 1953 civil rights leader Bayard Rustin, was arrested “on suspicion of lewd vagrancy” while on a lecture tour in Pasadena (“Lecturer Jailed on Morals Charge,” Los … Continue reading As quoted by the Los Angeles Times, the report then turned to the third degree:

Investigation by responsible lawyers leads them to believe that third degree practices are a serious evil in Los Angeles and the existence of these practices is borne out by independent investigation. It is said that in police headquarters there is an incommunicado cell which also is used as a third degree cell, and that here beatings take place. Screams have been heard and complaints from prisoners are frequent.[58]Although the scale of operations might differ, cf. Homan Square, the 21st century “black site” in Chicago.

In no other city in which there has been investigation by the commission have we found anything like the amount of discussion of police lawlessness that exists in Los Angeles.[59]All Report No. 11 passages are from “Los Angeles Police Hit.”

Perennials

In 2015 I searched an index of the Los Angeles Times and Los Angeles Sentinel on the topic of LAPD brutality cases during the first half of the 20th century. My survey was bookended with “Bloody Christmas” incidents beginning in 1909 (a drunken bricklayer on his walk home severely beaten after shooting an officer in the thigh) and ending with the notorious, systematic sadism of 1951 (backdrop to James Ellroy’s L.A. Confidential novel and film adaptation). The interim between these is peppered with many more yuletide abuses: third-degree tactics so pervasive they prompted a December 1928 threat of action by the local Bar Association president; death due to the ruptured gall bladder of a drunken CPA in December 1942 and the beating of a drunken aircraft worker the same night; three separate beatings in December 1947; a December 1948 skull fracture leading to the death of a drunken metallurgist; and the December 1948 beatings of a nightclub owner and two drunken patrons. If the incidences of brutality were perennial, so were the investigations they engendered. The cover was blown often, but with no relief. (Hughes 2015)

None of these cases involved sexual transgressions (at least as reported), but what sensible homosexual, upon being charged with lewd vagrancy and roughed up in the process, would go public with a counter-charge of brutality? Even Ramón Castellanos, whose case led to the suspension of Dale Jennings’s accusers, was reluctant. It was Deputy District Attorney Donald Avery—urged by internal affairs division head Lt. John Jesse—who interviewed Castellanos regarding his treatment. “Avery disclosed that Castellonos, during the interview, refused to sign a complaint against the officers” Martin and Porter “on the ground that it would serve no useful purpose.”[60]“Chief Suspends Two in Brutality Quiz.” After all, hadn’t the cops in question claimed Castellanos received his injuries at the hands of a flower pot? Such was the resignation homosexuals exhibited prior to the case of Dale Jennings, when the cover was blown for good.

Parallels

In 1972, LGBT folk in Denver began organizing, creating the Gay Coalition of Denver, first serving as a community center (without a space) and then addressing police harassment of gay men, including entrapment and arrest. On October 23, 1973, three hundred gays, lesbians, trans*, and allies packed a city council hearing on the matter, forcing the council to suspend its rules and listen to the throng. As recalled by Gerald Gerash (2001), one of seven attorneys who were parties to the suit:

On Oct. 24, 1974 (a year and a day after the City Council hearing), the court approved a settlement of our lawsuit […] and made it an order of the court—the police shall no longer enforce the criminal laws in a discriminatory manner against Gays, shall not “tolerate oppressive and harsh police activity against homosexually oriented persons or establishments where [they] gather,” that “kissing, hugging, dancing, holding hands…shall not be a basis for arrest” and that a liaison be appointed by the Police Dept. available to Gays and Lesbians, through the Coalition.

Almost exactly forty years later on October 15, 2014 in Long Beach, California, Rory Moroney was arrested for lewd conduct in a public park restroom. “Detective Raymond Arcala, an undercover decoy in the vice unit, said Moroney was masturbating in one of the park restrooms,” as reported in the Long Beach Press-Telegram. “Moroney, however, said Arcala’s eye contact and posturing indicated he wanted to have sex and wasn’t offended by the advances.” Long Beach Superior Court Judge Halim Dhanidina dismissed the case on April 29, 2016, granting a defense motion that enforcement had been discriminatory since LBPD’s vice unit employed only male decoys who targeted gay men.[61]“Judge says Long Beach police discriminate against gay men in lewd conduct cases,” Long Beach Press-Telegram, 29 Apr 2016, accessed 29 May 2016. I am grateful to my wife Andrea Carney for this.

On June 8, 2016, a driver in Regina, Canada was ticketed for taking off his seatbelt to give a panhandler some change. The beggar turned out to be an undercover cop.[62]“Good deed goes wrong,” 10 Jun 2016, CTV Regina, accessed 11 Jun 2016. I am grateful to my wife Andrea Carney for this.

¶ For an examination of the Mattachine’s engagement with the Mexican American community vis-à-vis police entrapment and brutality see “Harry Hay Meets His Match.” And read the last in this triad of articles, “Queer Questionnaire and Coates Column.”

References

Abbreviations: FBI = Federal Bureau of Investigation; ONGLA = ONE National Gay and Lesbian Archives at the USC Libraries

Alwood, Edward. 1996. Straight News: Gays, Lesbians, and the News Media. New York: Columbia University Press.

Charles, Douglas M. 2010. From Subversion to Obscenity: The FBI’s Investigations of the Early Homophile Movement in the United States, 1953–1958. Journal of the History of Sexuality, Vol. 19, No. 2 (May 2010), 262–287.

Cutler, Marvin. 1956. Homosexuals Today 1956: A Handbook of Organizations & Publications. Los Angeles: Publications Division of ONE, Incorporated.

D’Emilio, John. 1970s. Correspondence: Chuck Rowland. Interview notes: James Gruber, Harry Hay, James Kepner, Dorr Legg, Konrad Stevens, as listed below. In the possession of D’Emilio as of July and August 2009, and March 2014. I am grateful to John D’Emilio for providing me with copies of these documents.

——. 1976a. Notes from interview with Harry Hay, 16–19 Oct 1976, San Juan Pueblo, NM.

——. 1976b. Notes from interview with James Gruber, 28 Dec 1976, Mountain View, CA.

——. 1977. Notes from interview with Konrad Stevens, 05 Jan 1977, Los Angeles.

——. 1983. Sexual Politics, Sexual Communities: The Making of a Homosexual Minority in the United States 1940–1970. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

FBI. 1953 (09 Sep 1953). Two documents: 1) H. Rawlins Overton. Report: The Mattachine Foundation, Inc. […], ONE, Inc. Los Angeles. Case No. LA 100-45888. Declassified 02 Apr 1985. 2) S[pecial] A[gent in] C[harge], Los Angeles, to Director, FBI. Office Memorandum: The Mattachine Foundation, Inc. […], ONE, Inc. Internal Security – C. Declassified 06 Feb 1984. The latter document is a cover memo for the former 52-page report. The versions posted on the FBI’s Vault website are redacted differently from that posted on GovernmentAttic.org.

Gerash, Gerald. 2001. The Origins of The Center – How and Why It Came About. A drash delivered to congregation Beth Chayim Chadashim, 12 Oct 2001, composed 12 Jun 2001.

Gernreich, Rudi. Rudi Gernreich Papers, Collection 1702, UCLA Special Collections, Charles E. Young Research Library, UCLA. Boxes and folders in my text are rendered, e.g., Gernreich Papers 58:9. When I accessed the papers on 30 Jan 2010, the collection was unprocessed, so my references are based on the finding aid, accessed 06 Apr 2015.

Hay, Harry. Harry Hay Papers, GLC 44, Gay and Lesbian Center, San Francisco Public Library. Boxes and folders in my text are rendered, e.g., Hay Papers 11:36. I am grateful to Tim Wilson (SFPL) for providing me with the finding aid for this collection in 2009 before it was fully processed.

——. 1996. Radically Gay: Gay Liberation in the Words of Its Founder. Edited by Will Roscoe, Boston: Beacon Press.

Hobson, Emily K. 2014. Policing Gay LA: Mapping Racial Divides in the Homophile Era, 1950–1967. In The Rising Tide of Color: Race, State Violence, and Radical Movements Across the Pacific, edited by Moon-Ho Jung. Seattle: Center for the Study of the Pacific Northwest in association with University of Washington Press.

Hughes, M. David. 2015. Police Brutality. Unpublished manuscript of a survey of the subject in Los Angeles, 1900–1952.

Jennings, Dale. 1953. To Be Accused, Is To Be Guilty. ONE magazine. Vol. 1, No. 1 (January), 10–13.

Katz, Jonathan Ned. 1976. Gay American History. New York: Thomas Y. Crowell.

Mann, William J. 1998. Wisecracker: The Life and Times of William Haines, Hollywood’s First Openly Gay Star. New York: Penguin Books. I am grateful to Steve Duddy for introducing me to this book.

Mattachine. 1986. [Mattachine Pioneers Panel at the Celebration Theatre, Los Angeles, California, June 1, 1986.] DVD, Inventory No. 3125 M, UCLA Library. Accessed at ONGLA, Oct 2008.

——. 2008. Mattachine Society Project Collection, Coll2008-016, ONGLA. Boxes and folders in my text are rendered, e.g., Mattachine 2008 1:20.

ONE Incorporated. 2011. ONE Incorporated records, Coll2011.001, ONGLA. Boxes and folders in my text are rendered, e.g., ONE 2011 2:3 or ONE 2011 27:Hay when the folder is titled rather than numbered.

Slade, Eric. 2001. Hope Along the Wind: The Life of Harry Hay. Portland, Oregon: Eric Slade Productions. Eric Slade, director; Eric Slade and Jack Walsh, producers. My quotations are taken from the film itself, which differs slightly from the transcript obtained from the film website harryhay.com, April 2007 (since removed). I am grateful to Denah A. Johnston, Distribution Associate, Frameline, for making the DVD available to me.

Timmons, Stuart. 1990. The Trouble with Harry Hay: Founder of the Modern Gay Movement. Boston: Alyson Publications.

Tuchman, Mitch. 1987. Radical Faerie Consciousness. Unpublished manuscript based on interviews of Harry Hay conducted by Mitch Tuchman in 1981, 1982, and 1985. Accessed in Hay Papers 1:15–16.

White, C. Todd. 2009. Pre-Gay L.A.: A Social History of the Movement for Homosexual Rights. Urbana and Chicago: University of Illinois Press.

Text by David Hughes. © 2018 David Hughes. All rights reserved.