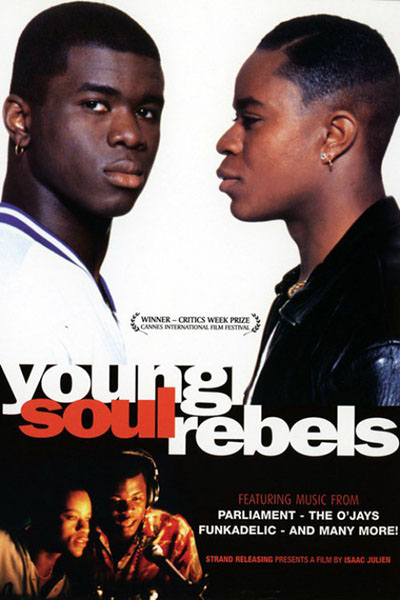

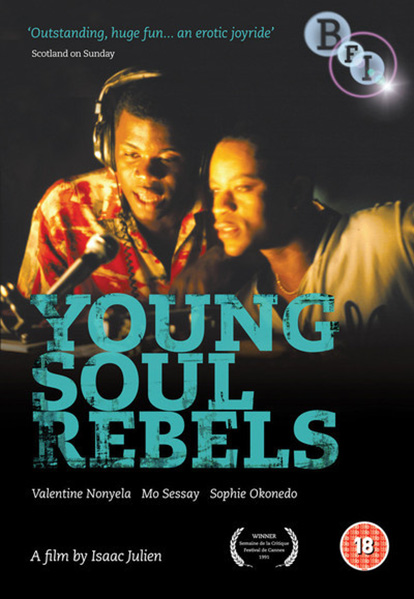

I’d say that I was disappointed by English black gay film-maker Isaac Julien’s 1991 “Young Soul Rebels,” except that my expectations were not particularly high. I think that his earlier short film “Looking for Langston” is overrated in part from sympathy for the difficulties Julien had with the heirs of Langston Hughes (who refused permission to use any of Hughes’s words in a film portraying his sexual orientation as gay). I liked Julien’s 2002 documentary on American blaxploitation movies, BaadAssss Cinema would like to see his documentary on Franz Fanon (“Black Skin, White Mask,” 1996) and some other shorter documentaries Julien has directed.

“Young Soul Rebels” (YSR) was Julien’s first feature-length film and first fiction film. Set in 1977 (Queen Elizabeth’s silver jubilee year, pre-Thatcher), it unconvincingly mixes the story of two young black (AfroCaribbean) DJs (Caz played by Mo Sesay is gay, Chris, played by Valentine Nonyela is straight) who have a pirate funk radio broadcast called “Soul Patrol” on weekends with a “thriller” story about a murder in a park that is closed at night but in which men connect sexually with men. Of course, the murderer is white and the victim black.

In turning off the Saturday night “Soul Patrol” program, the killer switched the boombox to recording instead of off. He then discarded the boombox in the bushes, where it was found by the younger sister of the straight DJ. Eventually, he plays the tape with the killer’s voice and come-on line. It is someone whom Chris knows, but he fails to recognize the voice. Of course, the killer comes after the tape, which leads to a lame chase and a fiery (literally) finish. There are unsubtle homages to “Blow-Up” (Antonioni) and “Blow-Out” (De Palma) in this plot, but a great deal of it is implausible to me, not least the resolution.

It provides opportunities for white policemen to menace Chris (who does not want to turn over the recording of the murder after having been accused of perpetrating it), but suspense and chases (indeed, any kind of action) are clearly not a Julien forte.

The intersection of race and (homo)sexuality is Julien territory. The heterosexual romance is not very convincing (and the black woman who works for the BBC and is trying to help Chris also has a white girlfriend, who, as played by Sophie Okonedo is particularly abstract or cardboard a character).

That the gay DJ is more conventionally masculine than the somewhat foppish straight one is schematic, but not unbelievable. I’m sure that there is some subtext about the contrast of intraracial heterosexual relationship in contrast the interracial gay and interracial lesbian ones, as well as the fatal park coupling. Someone as preoccupied with race/sex politics as Julien could not have failed to notice this schema that fits with the “race suicide” condemnation of homosexuality made by some black nationalists (most flagrantly, Eldridge Cleaver).

On the other hand, Dorian Healy as Ken, the earnest punk rock DJ (and distributor of the Socialist Weekly in an expensive designer t-shirt), is the only standout in the cast older than the girl (Danielle Scillitoe, I think) who plays Chris’s preteen sister.

The ending (after the “resolution” of the murderer stalking Chris and Caz part) is contrived, though providing gooey guilty “All You Need Is Love” pleasure.

The struggling entrepreneurs inevitably call to mind “My Beautiful Laundrette” (even if they are not getting it on with each other), a far better movie with far better performances all around. Both movies have menacing neo-Nazis in seedy East London areas. The city is not burned-out (despi te the conflagration near the end) as in Stephen Frears’ next (and considerably less good) movie about sex and race in multicultural Britain, “Sammy and Rosie Get Laid.” The upbeat finales of it and YSR (and the French coming-of-age romantic comedy “Just a Question of Love”) are especially similar, but primarily in biting off of more than the film-makers can chew.

te the conflagration near the end) as in Stephen Frears’ next (and considerably less good) movie about sex and race in multicultural Britain, “Sammy and Rosie Get Laid.” The upbeat finales of it and YSR (and the French coming-of-age romantic comedy “Just a Question of Love”) are especially similar, but primarily in biting off of more than the film-makers can chew.

The audience roots for Caz and Chris to succeed, but it is difficult to muster much enthusiasm, because they are such unoriginal “rebels,” and Chris is so eager to sell out. Perhaps if I had been able to see the movie in 1991 (or some time before “Noah’s Arc” debuted on cable), I’d have found it fresher, though the amateur detective/thriller part would have seemed just as perfunctory and unsatisfying to me.

Nina Kellgren cinematography is good and the sound-track is lively, but the writing and/or editing and/or directing make for an odd combination of jerky and rambling. The sex scenes are inept (protracted without being graphic).

—-

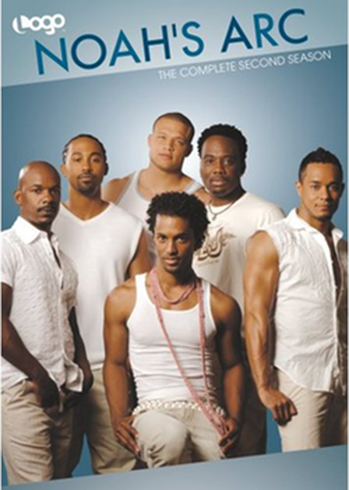

I guess that I have to consider the Logo series “Noah’s Arc” a guilty pleasure. It is a black gay soap opera, more romantic comedy than the all white English and American(/Canadian) versions of “Queer as Folk,” with less focus on Issues. A gay black “Friends,” perhaps?

Like “Friends,” it is difficult for me to believe that the characters in “Noah’s Arc” would be friends. It is easier to imagine that the other three characters who were already a group at the start of the series (in 2004) were all friends with Noah. Noah is sweet and caring and very attractive, and I was a fan of long standing of Daryl Stephens who plays Noah. While an undergraduate student at Berkeley, Stephens had been a standout member of the John Fisher troupe that mixed ironic postmodernist commentaries with gay stories and music of various kinds around the Bay Area. I’m not sure if Stephens was in the outdoor (moving around within Yerba Buena Gardens) production of “Titus Andronicus,” but I know that he was in “The Gay of Joy Sex” and played Jason in the group’s biggest cross-over success, “Medea, the Musical.”

Stephens is much more fey as Noah than he was in those plays, but he is a fierce queen. The second season provides him an invitation from his boyfriend to parade himself in public as a victim, but Noah refuses to do that. Men fall in love with him, including two dissimilar except in being hypermasculine men in the second season along with the two strong, silent types whose heart Noah had captured during the first season.

Next to Noah and the most intense of his love partners, Wade (Jenson Atwood), who have chemistry to spare, my favorite character from the first season was Ricky (Christian Vincent), a very muscled sex machine who had tricks in 1970s abundance but had never fallen in love. In the second season, Ricky has an unfortunate Mohawk and less comic material, since he Falls in Love—and with someone who is HIV+ and interested in topping him (Wilson Cruz, grown up and worked out since “My So-Called Life” and “Johns”!).

Work (writing screenplays) and Love are tied together for Noah, whose break in the business was being hired to rewrite Wade’s script. In the second season, the brash British rapper “Baby Gat” (a scene-dominating, if not -stealing, Jason Steed) who is going to star in it courts Noah in private and is a nasty straight boy in public.

The other two of the original four black gay Santa Monica musketeers are Chance, a college professor at the start of his career, played by Doug Spearman, and Alex (played by Rodney Chester) at which Junicho (Cruz) works and Alex’s friends (including Ricky) are inveigled into volunteering at. Alex and hist partner, Eddie (Jonathan Julian) are the model couple, raising a child named Kenya (the sassy Sahara Davis) together. My favorite segment involving them is the one in which Alex figures out how to get Eddie to stop permitting Kenya to sleep between them every night.

Alex is the character most prone to melodramatic hysteria. Everyone, beginning with his partner Dre (the very pumped-up Merwin Mondesir), thinks that Alex is paranoid that Dre’s straight buddy Guy (the drop-dead gorgeous Benjamin Patterson) is trying to steal Drey for himself. Even paranoiacs have real enemies, as the old saw goes. (I don’t see why there would be a competition for Dre; one for Guy I could easily understand).

The first season was mostly romantic comedy. In the second (and, apparently last, though there is going to be a feature movie), issues of bashings, adoption, serostatus discordance, (in)visibility, exploitation, and hypocrisy are more central. (Both present dim views of black men on the “down low”).

Aside from sparing the viewer commercial breaks and providing commentary tracks, the DVDs are far superior to the broadcast series, because there are “digisodes” included—whole scenes supplementing the half-hour episodes. Some of the best (not to mention edgiest) scenes are in the digisodes. Anyone who enjoys the series, owes it to himself or herself to include these supplements.

It seems that many of the “deleted scenes” are scenes that were included in the main program from which sometimes unnoticeable moments have been cut, but there are also some scenes that seem key to me.

The half-hour programs seem too short. I wish that they had been hour ones, less rushed with more development (but even less Dre…), and I wish that there was a director’s (un)cut, putting most of the digisodes and some of the deleted scenes back into a continuous narrative (rather than a document with the opening and closing credits of each episode).

I had to ration myself to keep form zipping through the whole season in a night. Although Darryl Stephens is a very skilled comedian , I’d like to see him in a major dramatic part. And, though he can also bring off the outlandish outfits Noah has, his body looks better (and I’d be happy to have it all on display…)

The series was apparently popular with black women—after all, they also have to deal with black men, right?—and a multicolored gay audience. I doubt its wider appeal, but I found it very entertaining, even beyond looking at the semi-dressed cast.

(Julien is now a media studies professor at the Universityof California, Santa Cruz half the year.)

©27 June 2007, Stephen O. Murray