May 23, 2002.

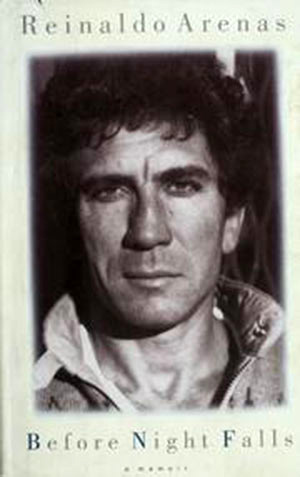

The memoir Before Night Falls, which Cuban writer Reinaldo Arenas (1943–90) dictated before his death, is a searing document of resistance to (and complicity with) tyranny, specifically the surveillance state of Fidel Castro.

Many of Arenas’s writings were seized by Cuban police, though manuscripts of at least half a dozen of his novels were smuggled out of the country. As the memoir makes quite clear, after escaping in the Mariel exodus, Arenas was less than enthralled with life in the United States. Being flamboyantly homosexual, he had uneasy relations with the anti-Castro patriarchs of Miami. Having been sexually imprinted on Cuban machos and acculturated in a hyper-gendered kind of homosexuality repugnant to gay Americans, Arenas was also dissatisfied with “modern gay” life that did not provide him “straight” men as sexual partners.

Many of Arenas’s writings were seized by Cuban police, though manuscripts of at least half a dozen of his novels were smuggled out of the country. As the memoir makes quite clear, after escaping in the Mariel exodus, Arenas was less than enthralled with life in the United States. Being flamboyantly homosexual, he had uneasy relations with the anti-Castro patriarchs of Miami. Having been sexually imprinted on Cuban machos and acculturated in a hyper-gendered kind of homosexuality repugnant to gay Americans, Arenas was also dissatisfied with “modern gay” life that did not provide him “straight” men as sexual partners.

I see Arenas not only as having been a martyr to the revolution he initially enthusiastically supported (that is, Castro’s) but to the system of machismo that he worshipped even more than the Cuban communists did/do. If macho rural Cuba had been such a paradise as Arenas convinced himself it had been, he would not have joined the rebels or moved to Havana. (Some of the early euphoria is on view in the 1965 story “The Parade Begins.”)

Both Arenas’s sexual politics and his fury at the human costs of the Castro dictatorship are more than relevant to Mona and Other Tales, the collection of short fiction from across Arenas’s writing career (1963–1987): they are central. Arenas often went off into extended lyrical riffs about sights and smells and sounds of the tropical island on which he was born and from which he was painfully exiled. I don’t know if it is that I am not particularly responsive to these or whether they can not really make the migration from Spanish to English: this is the kind of writing that seems inflated, empty rhetoric in the cold print of English (like Castro’s speeches).

Much of Arenas’s fiction seems to me not merely episodic but laxly structured. In particular, I found The Ill-Fated Peregrinations of Fray Servando unreadable. It is not that I admire only Before Night Falls (though I think that is a very great book). The tightly focused and intense (into the hallucinatory) El Central and the two novellas collected in English as Old Rosa are compelling. (I have trouble with what I see as the homophobia of The Doorman, the last novel Arenas wrote.)

None of the stories collected in Mona and Other Tales is compelling. The most impressive is the title novella, which purports to be a manuscript by a man who attempted to smash the “Mona Lisa” while it was on loan to the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, with annotations from two editors, one from 1999 (which was still in the future when the story was written in 1986), and the other from 2025. The notes do not take up more space than the text (as in Nabokov’s Pale Fire) and are amusing. The outlandish madman’s/criminal’s tale is inventive (also in Nabokovian ways).

The well-crafted “The Glass Tower” (also from 1986) is also set in America (Miami rather than New York City). In it, exiled Cuban author Alfredo Fuentes spends all his time being fêted and (quite literally) patronized, while he desperately wants to write before his characters abandon him. They are clamoring for attention (as in Pirandello’s Six Characters in Search of an Author).

The well-crafted “The Glass Tower” (also from 1986) is also set in America (Miami rather than New York City). In it, exiled Cuban author Alfredo Fuentes spends all his time being fêted and (quite literally) patronized, while he desperately wants to write before his characters abandon him. They are clamoring for attention (as in Pirandello’s Six Characters in Search of an Author).

“End of the Story” (1982) is one of Arenas’s passionate elegies to a compatriot ground up by the Cuban regime of terror, addressed from Key West to the sea and the lover who committed suicide.

“Halley’s Comet” (1986) imagines (burlesques) the characters from García Lorca’s The House of Bernarda Alba having lived on after the end of the play (this requires reviving the dead daughter), gone to Cuba, and after decades of seclusion sallying forth in what they believe is the earth’s last hour before the comet strikes it.

“The Parade Ends” (1980), a 30-page long paragraph, invokes the crush of those seeking asylum in the Peruvian embassy that was a prelude to the Mariel exodus. The increasingly hallucinatory account has more value as a historical document than as fiction, though this verdict could be applied to the collection as a whole.

The stories that were written in Cuba tend to magic realism and are shorter than most of those from Arenas’s American exile. The best of the earlier stories is “With My Eyes Closed” (1964) told by an eight-year-old. Some (e.g., “The Empty Shoes” and “Blacks”) strike me as completely inconsequential. None of the stories collected here are plot-driven. Some of them don’t seen character-driven to me, either (e.g., “The Great Force,” which is wickedly amusing, and “Blacks,” which is DOA).

In addition to the fourteen stories (that fill only 190 pages), there is an interesting (9-page) 1988 essay “The Joyful Sixties in Latin American Literature” on the florescence between 1962 and 1968 of “extraordinary novels,” including two whose authors Arenas came to despise as running dogs of Fidel Castro: Gabriel García Marquez’s One Hundred Years of Solitude and Alejo Carpentier’s Explosion in the Cathedral; plus Arenas’s master José Lezama Lima’s Paradiso, fellow Cuban exiles Guillermo Cabrera Infante’s Three Trapped Tigers José Donoso’s Obscene Bird of Night, Julio Cortázar’s Hopscotch, and Mario Vargas Llosa’s The Time of the Hero.

Besides their exuberant technical innovations, what particularly struck Arenas about what became in translation a bit later a “Latin American boom” is that with the exception of Lezama, who was in internal exile in Cuba, these writers were writing far from their homelands. The authors were (then) “adventurers and pariahs who had made the whole world into their own homeland, and creativity into their only faith.” Arenas was obviously trying to convince himself that exile was a normal state for a Latino writer and reminding himself that what had become a canon of masterpieces of Latin American fiction had been written in exile in London (Cabrera and Vargas), Paris (Carpentier, Cortázar), and Mexico City (García Marquez). So why not New York? (Arenas was already in declining health, and it seems to me it was left to the Colombian New Yorker Jaime Manrique to add the New York of the 1980s to this canon.)

Except for the dazzling body of work of Jorge Luis Borges (who was intensely influenced by writers in English such as Chesterton, Stevenson, and Poe), the short story does not seem to be a genre in which Latin American writers have triumphed. García Marquez wrote some important novellas, and some of Cortázar’s stories are interesting, but the novel has been a much more comfortable a medium for the major Latin American writers of the last half century.

I do not know what the criteria for selecting the stories included in this volume were, and the order of them, other than ending with “The End of the Story” is also obscure to me. I don’t know that putting them in chronological order would have provided any illuminations, but it would at least have been an order.

I think that Reinaldo Arenas is an indispensable witness to tyranny. Mona and Other Tales is indispensable to those interested in Arenas, but it does not contain Arenas’s indispensable work and is not the best introduction to it. (I’d say El Central is that.)

published by epinions, 23 May 2002

©2002, 2016, Stephen O. Murray