Wild Animals I Have Known: Polk Street Diaries and After

Wild Animals I Have Known: Polk Street Diaries and After

by Kevin Bentley

Published by Green Candy Press

Published January 1, 2002

History (memoir)

270 pgs. • Find on Amazon.com

Reviewed by Stephen O. Murray

June 28, 2002.

Wild Animals I Have Known: Polk Street Diaries and After is a chronicle of “the good old days” when we thought we were attaining or even living gay freedom.

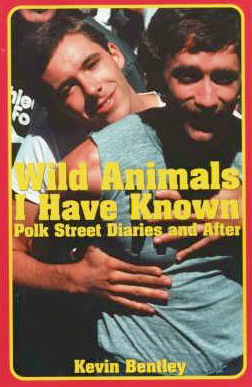

The cover shows a close-up of a 1970s Gay Freedom Parade in San Francisco. Author Kevin Bentley moved to San Francisco a bit farther than I did (from El Paso rather than Tucson), and a year earlier than I (1977).

In the San Francisco of the late-1970s, sex was readily available: it was “the golden age of promiscuity.” It is not that gay men then were not trying to establish and sustain long-term relationships, but these were particularly difficult for those emerging from the depressions and repressions of adolescence feeling different, unloved, and unlovable. Many of us had felt we were the only one who had feelings of attraction for our own sex, and suddenly there were others—many, many others, many others also making up for the lost time of tormented adolescences.

The entries that Kevin Bentley has chosen to publish from his “Polk Street Diaries” of that era are primarily about sexual adventures, often comic misadventures. Anyone who does not want to read about men having sexual encounters with men should steer away from this book. Like Renaud Camus’s Tricks from the same pre-AIDS era, Bentley was finding out who the men he met were through sex: what they did, how they did it, and the places they lived. It was often the books (or the total lack of books), the recorded music (LPs then), and the artifacts in a trick’s room or apartment that made incompatibility obvious.

As wild and promiscuous as Bentley’s 1970s life will seem to many people now, he was at the time fairly old-fashioned in that he tricked, that is, went home with men to have sex. Many gay men prefer (and preferred) the safety of commercial venues and anonymity there and elsewhere. Many of us avoided the risk that once someone who looked “hot” started speaking, he would cease to seem desirable, and had sex before risking conversation, let alone going to where the man lived or taking him home with us. As Bentley said at a reading I attended, he felt at the time that everyone was getting laid more than he was. In that all of us had friends or acquaintances who had more sex and more partners than we did, I think that “I’m not getting laid that much” was common.

“Getting laid” was a focus then and there for gay men (and for most young men most of the time in other eras and locales). However, it was necessary to make a living to have a place to live and to pay bar cover charges (and, perchance, to eat, but this was a low priority in it what was not a gourmet era). Gay novels of Manhattan/Provincetown/Fire Island sex, drugs, and disco elide this, leaving readers to guess how the characters acquired money. Something I particularly appreciate in Bentley’s book, as in Jim Grimsley’s recent novel Boulevard, which also recounts moving to a gay ghetto, is chronicling the difficulty of making a living. Grimsley’s protagonist worked in a porn shop; Bentley’s first San Francisco job was in a (heterosexual) porn theater. (He later got a job in a Tenderloin non-pornographic bookstore.)

In addition to the stream of tricks, there were friends. Eventually there was a lover. And then there was AIDS. The most interesting of Bentley’s friends and two lovers die of it. Like me, Bentley survives through some accident of genetics (ours or our viruses). We know that “promiscuity” sped HIV through the gay community, but we also know that the cause of AIDS is a virus, not “promiscuity.” Indeed, targeting “promiscuity” provided many the illusion of safety in having unprotected sex over and over with an infected partner (part of what the Swedish investigator Benny Henriksson dubbed “the risk factor of love”).

Bentley does not provide a retrospective interpretation, and he paid no attention to AIDS prevention politics or to any other kind of politics. In this, he is like the fictional inhabitants of 28 Barbary Lane. Less sexually adventurous than Bentley, and writing in a “family newspaper,” Armistead Maupin in his well-known Tales only hints at what life was like for gay men during “the golden age of promiscuity.” Written at the time (though culled recently), this book tells it like it was—without apologies, without shame, and without the chauvinism of “lgtb pride.”

My 300th epinions on 28 June 2002

©2001, 2016, Stephen O. Murray