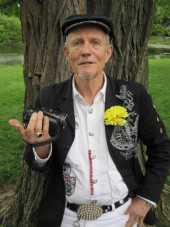

Randy Wicker:

Randy Wicker:

Memories of gay activism, 1959 to 1970

Profile by Randy Wicker

September 13, 2007.

As a teenager during the 1950s, I knew I was homosexual. “Queer” wasn’t “catchy” & “in” then. “Queer” was a hateful epithet that caused pain. In high school, rednecks called me “Que-bo” behind my back.

In the 1950s, the media covered homosexuality as crime: Leopold & Loeb, child killers; Burgess & McLean, British spy-defectors to the Soviet Union; police raids on “pervert” events with photos of drag queens sitting in a Paddy wagon. Only Confidential Magazine covered “all the news unfit to print” about celebrities’ real or alleged homosexual activity.

At seventeen, I read a pulp novel describing a gay bar. I was ecstatic! There were actually places where homosexuals gathered and socialized! Library books only talked about “causation” and the “mental suffering” of the “afflicted.”

Similar experiences motivated Barbara Gittings, the 20th century’s most effective lesbian activist, to wage a 50-year life-long campaign against what she called “the lies in the library.” Today, books about gay civil rights sit next to “the lies in the library”—thanks to Barbara Gittings.

In 1956, I sought out “gay life” in Greenwich Village. “Gay” was strictly an in-group term in those days, a word you’d use to test another person’s reaction. I bought The Mattachine Review and ONE magazine at a newsstand, subscribed, and read them eagerly the next college year.

I had no problem accepting my homosexuality. I only feared discovery. As a college freshman, I kept a diary that detailed the crush I’d developed on a fellow student. My Father found my diary and read it. Fortunately, the psychiatrist he consulted advised him that I’d always be homosexual.

Father confronted me. He believed “circumstances” had caused my homosexuality. He recalled how I’d cried about ‘Mommy deserting me’, at age five, when she was taken away with tuberculosis.

“I want you to be the best adjusted homosexual you can become,” Daddy told me. “I won’t always be here to take care of you. I haven’t told your Mother because she could never accept it.” (Mother never really did.)

I invited my Father to accompany me to “Lenny’s Hideaway,” a Greenwich Village gay bar where he would have met an impressive assortment of Ivy League School students, young lawyers and other professionals, etc.

“I can accept you,” Daddy explained while declining, “but I can’t accept them.” (Ironically, I’d discover later that he’d hired a private detective who’d followed me there.)

I eagerly showed my Father Mattachine Society literature a few months later and told him I was becoming involved as we shared lunch.

“It’s your life to live,” he surmised. “I don’t think you are going to get very far with this. I ask just one thing—that you not involve my good name.”

My given legal name was “Charles Gervin Hayden Jr.” I chose “Randolfe Wicker” as my new name. After work, Charlie Hayden morphed into Randy Wicker, a fearless champion of truth and justice. In 1967, I legally became Randolfe Hayden Wicker.

Perceptions of homosexuals outraged me. Legally, we were criminals. Psychiatrists called us mentally ill. Religious folk considered us moral degenerates. The homosexuals I knew were well adjusted, looked and acted normally, held jobs and were generally indistinguishable from others.

I sought out the New York Mattachine Society in June, 1958, lied about my age to meet their “twenty-one or over” age requirement, and joined. Several of the older members were informed, educated and articulate. However, none felt able to be public spokesmen.

My promotion of Mattachine’s monthly lecture attracted 300 people versus the usual 30. The landlord evicted Mattachine Society because there was a bar at street level. (The vice squad had visited him.) It was illegal to serve homosexuals a drink or allow them to gather in those days. In 1965, we demanded service at Julius Bar in Greenwich Village, challenged and changed the law.

On NYC’s WBAI FM , a panel of psychiatrists boasted they could “cure any homosexual” with “just eight hours of therapy.”

“Those shrinks are ‘frauds’ seeking vulnerable patients to exploit!” I complained to the station brass. “We ‘homosexuals’ are the real authority on homosexuality! We live it 24 hours a day!”

The resulting program, “Live and Let Live,” captured a full page in Newsweek, was favorably reviewed by the New York Times, and became a major news story. WBAI’s license was challenged. The FCC ruled “homosexuality was a fit subject for public discussion.” Radio & TV stations wanted panelists. Mattachine’s sole spokesperson was Randy Wicker.

I worked with the Robert Doty, the New York Times reporter exposing “one of the city’s best-kept secrets”—the “existence of a large homosexual community in NYC.” I gave him Evelyn Hooker’s study and begged him to include the “minority viewpoint” that “homosexuality, in and of itself, was not a mental illness.” However, he only used “all-gays-are-sick” psychiatrists.

The New York Times Index (1963) describes a news story: “R. Wicker calls for acceptance of homosexuals as legitimate minority group.” I’d talked at City College in Manhattan to an overflow audience of 400 students. The Times printed that story on their “Women’s Page.”

During the mid 1960s, I concluded efforts to turn the struggle for homosexual civil rights into a mass movement were futile. In 1965, the “gay movement,” founded fifteen years earlier by Harry Hay, included only a few hundred people. Its existence really depended on a couple dozen activists.

Where did I get the nerve to organize the first public demonstration for homosexual civil rights (U.S. Army Induction Center in NYC, 1964); give gay liberation a voice on the airwaves (1962); be the first unmasked gay activist face on television (NYC 1964)?

Homosexuals, including most gay activists, believed they would be physically attacked (or worse) upon publicly identifying themselves. But by stepping out of the closet and “speaking truth to power,” I found people curious, respectful, willing to listen to dissenting viewpoints.

By 1964, I’d become a passionate opponent to the War in Vietnam. My best friend’s girlfriend nearly died terminating an unwanted pregnancy. Other friends turned me on to pot, and I’d become naively enamored by it. I joined the anti-war, sex freedom, and legalize pot movements.

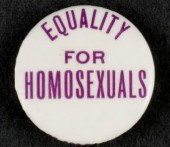

Publishing “issue buttons” was my hobby. “Equality for Homosexuals” was my first big success. By 1967, my hobby had become a lucrative business. I became the “Button King” of the hippie era.

Publishing “issue buttons” was my hobby. “Equality for Homosexuals” was my first big success. By 1967, my hobby had become a lucrative business. I became the “Button King” of the hippie era.

In 1969, Stonewall happened. I realized I’d given up prematurely on the gay community. I watched our Annual July 4th demonstration in Philadelphia at Independence Hall be flooded with newcomers the next week and become NYC’s First Gay Pride Parade in 1970.

In my lifetime, homosexuals have gone from being criminals to being a legitimate minority group. We may not have full equality yet, but we’re slowly getting there. I’ve watched young activists go to lobby politicians on gay issues, end up being hired by them and have careers as openly gay civil servants.

Our right to be, to love, to lobby, to be licensed professionals, to assemble, even to drink, are now taken for granted.

I see continuing progress ironing out the shortcomings of our society. Our right to marriage and military careers are simply a matter of time. I love this country! Today’s improved status for gays, women and minorities shows how free speech has transformed the USA!

Randolfe (Randy) Wicker

Hoboken, NJ

Photograph by Ryan Wolowski. See also the Interview with Randolfe Wicker by Raj Ayyar, on GayToday.com.