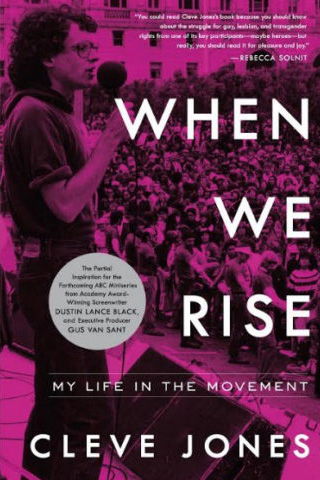

When We Rise:

When We Rise:

My Life in the Movement

by Cleve Jones

Published by Hachette Books

Published November 29, 2016

Nonfiction (memoir)

304 pgs. • Find on Amazon.com

Reviewed by Stephen O. Murray

January 21, 2017.

I enjoyed Cleve Jones’s memoir When We Rise: My Life in the Movement.

I first heard of and heard him when he spoke outside San Francisco City Hall at the end of the eerily silent candle-carrying march from the Castro the night Harvey Milk and George Moscone were assassinated (27 November 1978). I don’t remember what he said then, or what Harry Britt said that made me write to urge Dianne Feinstein, who had become mayor due to the murders committed by her protégé, Dan White, to appoint Britt to complete Milk’s term. (The visual I remember is many candles burning on the statue of Abraham Lincoln at City Hall.)

That somber night that brought Cleve Jones to my notice, when he was barely 24, occurs more than half way through his memoir—which is just fine with me, because I found the account of moving to and scrambling to live in 1970s San Francisco very interesting.

Although he is four years younger than I am, he got to the San Francisco Bay Area from Arizona four years earlier than I did. Both of us spent that autumn of 1978 campaigning against the Briggs initiative (Proposition 6). He was concerned with taking the campaign out of the liberal strongholds, while I was going door to door in Contra Costa County (which was more conservative then than now). I think it odd that there is practically nothing about the San Francisco victory party (at which I saw and heard both Moscone and Milk, the only time I saw and heard Moscone in person), when the initiative lost by more than a million votes, even losing in Briggs’s home Orange County.

The great victory, the first defeat of an anti-gay initiative, was followed all too closely by the Jonestown mass suicide, and the carnage in City Hall. And the trial of Dan White that ignored the coup aspects of assassinating the leftist mayor and the gay rights crusader and police coddling of the assassin led to the “White Night Riot,” that Jones reports well.

He sort of races through his public projects and private life after that, though several speeches are reproduced. Jones has written before about the AIDS Quilt (NAMES project). From the edge of the abyss, he was saved by a drug combination (I think 3TC was the one that saved him, and I’m sure he moved on to better combinations than the first one).

What he writes about the making of the 2008 biopic Milk (for which he was a consultant: he was the first person Dustin Lance Black thanked in accepting an Oscar for his screenplay) is interesting as his backstage maneuvering to avoid disruption of the international AIDS meeting in Montreal in 1989 and his work for Unite Here, the union of hotel and restaurant employees. Indeed, Jones documents the forging of gay and labor ties going back to the Teamster’s Coors boycott (though ignoring what Harry Britt did as supervisor, both in coalition-building and in gay rights legislation).

Jones provides a lot of context that I knew, but can appreciate is useful for many readers, especially those who did not live through the times about which Jones writes. The memoir does not stint on the “sex, drugs, and rock’n’roll” (plus disco and punk) of being a young refugee in San Francisco, nor on the bullying Jones experienced growing up in Indiana and in Arizona (West Lafayatte and Scottsdale).

One minor mistake is having the first President Bush taking office on 29 rather than 20 January. And having heard it more than a few times, I’m sure that rather than “media queen,” Jones was called by some a “media whore.” He was media savvy early, and provides solid analyses of mistakes (especially the Proposition 8 campaign) as well as triumphs.

©2017, Stephen O. Murray