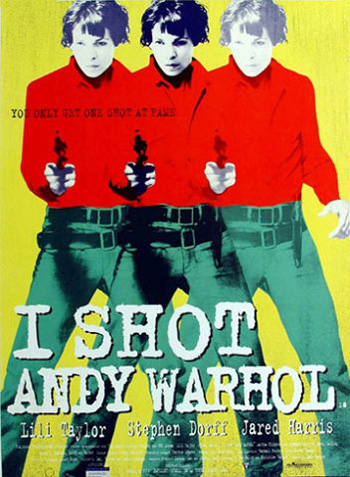

I Shot Andy Warhol

I Shot Andy Warhol

Directed by Mary Harron

Written by Jeremiah Newton, Diane Tucker, Mary Harron, and Daniel Monacan

Released January 20, 1996 at Sundance Film Festival

History (biography, drama)

103 min.

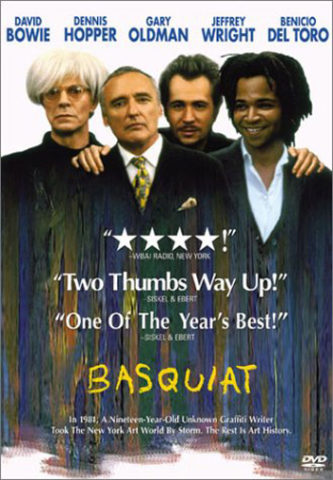

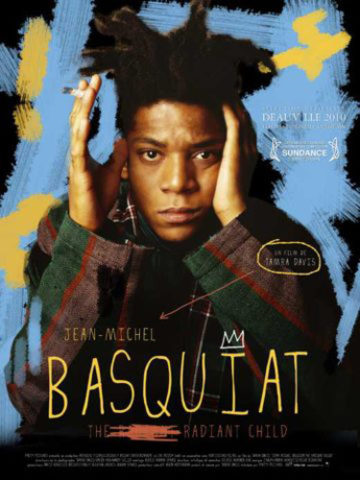

Basquiat

Written and Directed by Julian Schnabel

Released August 9, 1996

History (biography, drama)

108 min.

Review by Stephen O. Murray

January 9, 2002.

In I Shot Andy Warhol, Lilli Taylor turned in a bravura performance as the mouthy, man-hating sometimes prostitute, sometimes panhandler, and writer Valerie Solanas in Mary Harron’s jump-cut evocation of the late-1960s when all sorts of social revolutions were being seriously proposed and Andy Warhol (played by Jared Harris, son of Richard) was mumbling in his film factory and cashing ever larger checks for his paintings.

Lothaire Bluteau (who played Bill in Urbania) is elegantly handsome as Maurice Giordias, the suave publisher of the Olympia Press, who contracted two novels from Valerie Solanas. He really did have control over what she had not yet even written, and, had he not been out of town, she would have shot him instead of Warhol (and thus attained less notoriety and been unlikely to have had a movie made about her). The same would be true if she had gunned down Paul Morissey (played by Reg Rogers), who is portrayed as baiting her, Warhol being highly adverse to conflict. Stephen Dorff plays Candy Darling, who provided initial entrée to the Warhol circle to Solanas.

A very similar sounding Warhol (played by David Bowie) shows up in Julian Schanbel’s 1996 biopic about Jean-Michel Basquiat (played by Jeffrey Wright, before Ride with the Devil). There’s not much narrative drive (less than in Before Night Falls, but Arenas supplied much of that in his book) or much character development, but there is great character portrayal by Bowie, Wright, and uncredited roles played by Willem Dafoe and Christopher Walken.

A very similar sounding Warhol (played by David Bowie) shows up in Julian Schanbel’s 1996 biopic about Jean-Michel Basquiat (played by Jeffrey Wright, before Ride with the Devil). There’s not much narrative drive (less than in Before Night Falls, but Arenas supplied much of that in his book) or much character development, but there is great character portrayal by Bowie, Wright, and uncredited roles played by Willem Dafoe and Christopher Walken.

Jean-Michel doesn’t devolve or evolve. He becomes an overnight sensation and has more money, but he continues to be amiable but somewhat dissociated (even when not drugged). His hands are more articulate than his tongue, but he is sweetly rather than menacingly inarticulate verbally.

Schnabel illustrates some scenes from Basquiat’s life and shows him convincingly at work (both painting and obliterating, most notably in collaborative work undoing what Warhol did). Any connections between Basquiat’s mother’s madness and his psychopathology is left open for the audience to plug in as it sees fit.

One of the more poignant scenes is his attempt to join with some young men painting graffiti in the street. The fame of graffiti-sprayer is fleeting and they don’t recognize the former king (“Samo”) and beat him up. Jean-Michel holds his own better in a TV interview with Christopher Walken (playing a Mike Wallace-like shark of a journalist) trying to provoke him. I especially enjoyed his faux-naive response to “Do you consider yourself a black artist?” “Black is only one of the colors I use.” To the provocation of “How do you respond to be labeled ‘pickaninny of the art world’?” he winces and then asks who called him that, and then he corrects the quotation.

Gary Oldman plays Schnabel (with Schnabel paintings, Schnabel’s daughter, and presumably Schnabel’s warehouse) to no particular effect. I guess it’s supposed to be a defense: “I tried to help, to be his friend, to cook for him. I even left him alone with my young daughter!”

Despite being cast aside, the film-maker Benny (Benicio del Toro, pre-Traffic) rescues Jean-Michel from the streets, just as he did before he was famous. Dennis Hopper as art patron/dealer Bruno Bischofsberger shows concern and Warhol is shown as being generously supportive, untroubled by what he regards as Basquiat’s superior artistry. He tries to get him to a dermatologist. He tries to get him off drugs.

Despite being cast aside, the film-maker Benny (Benicio del Toro, pre-Traffic) rescues Jean-Michel from the streets, just as he did before he was famous. Dennis Hopper as art patron/dealer Bruno Bischofsberger shows concern and Warhol is shown as being generously supportive, untroubled by what he regards as Basquiat’s superior artistry. He tries to get him to a dermatologist. He tries to get him off drugs.

Indeed, no one is shown as using the young black artist. Art-dealer Mary Boone (played by Parker Posey) clearly wanted to, but he changed galleries frequently. Courtney Love’s Madonna figure isn’t around long enough to sink her fangs into him. Writer René Ricard (played very well by Michael Wincott) is more sinned against than sinning (the sin of exploiting Jean-Michel)—perhaps because he more than any other single person made Schnabel an art-world sensation. So there is no narrative explanation for his burning out so fast (dead at 28 of a heroin overdose, nine years after his first Manhattan gallery show). Does Schnabel suppose Basquiat couldn’t live without Warhol around and followed him into death? Or can he be accused of covering up the true viciousness of the New York art scene in which he also rocketed to fame at about the same time as Basquiat?

The soundtrack is very eclectic, including the climax of Gorecki’s Symphony No. 3, Tom Waits, Keith Richard, David Bowie, Public Image, et al.

The film is visually rich (more so than Schnabel’s own paintings!), and I suppose one could argue that an incoherent life is best represented by a jumpy, incoherent biography. (There is a published biography, but I’ve only looked at its pictures, so can’t compare it to the screenplay for which Schnabel credited himself.) Or one might claim that the crowned black child from the opening credits (Jean-Michel taken to the Museum of Modern Art when it had Guernica) is the same child of the final story (the mute, white prince banging his crown against the bars of his prison tower window, making a beautiful sound from his anguish) and that both are metaphors for Jean-Michel Basquiat.

Published by epinions, 9 January 2002

©2002, 2016, Stephen O. Murray