A review of the book by Martin Aston.

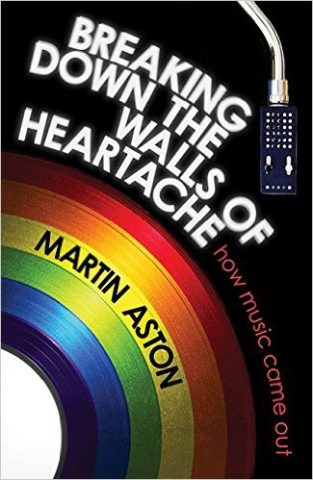

Breaking Down the Walls of Heartache:

Breaking Down the Walls of Heartache:

How Music Came Out

by Martin Aston

Published by Backbeat Books

Published June 1, 2017

Popular Music

592 pages

Reviewed by David Hughes

Posted May 15, 2017

Author and journalist Martin Aston certainly has taste.

For a stateside fan of British pop music like myself, Aston’s CV reads like a browse through my record collection. His debut in print was a review of a live New Order gig in 1984. He did A&R for Rough Trade Records.[1]I unwittingly picked up the label’s 1977 debut 45, by the French band Métal Urbain.

Aston’s first book was Pulp (1995), about the Britpop band by that name that reveled in fop (and, just as Rough Trade’s Scritti Politti had done with its single sleeves, one of which is pictured here,[2]It’s worth pointing out that in 1974, four years before Scritti Politti’s first single, John Lauritsen and David Thorstad published The Early Homosexual Rights Movement (1864–1935) under the … Continue reading Pulp dared to deconstruct the notion of the music video with its “Babies”).

Aston’s second book was fittingly called Björkgraphy, if one were to appreciate the graphic sense in the title’s combining form, since the Icelandic singer comes as a package: sound + vision. He edited the series Divas (2000), which portrays Billie Holiday, Judy Garland, Aretha Franklin, and Barbra Streisand. 2013 saw the publication of Facing the Other Way: The Story of 4AD, which profiles the label’s mastermind, Ivo Watts-Russell, reviver and contriver of the supergroup for a new generation via This Mortal Coil and whose record jackets were as revolutionarily evocative as his roster of musical artists was sonically elastic.

Although a couple of years younger than me (I was born in the summer of ’55), Aston’s first purchased single was the Supremes’ “Where Did Our Love Go” from 1964, whereas I, the late bloomer, wouldn’t get my first 45 until ’67—Johnny Rivers’s cover of The Miracles’ “Tracks of My Tears.” (It was Rivers’s on-again-off-again facial hair that first alerted me to the mutability of pop’s makers of music.)

Aston eschewed the Beatles and Stones for the “dynamic and sweeping melodramas” of Dusty Springfield, Cilla Black, and The Mamas and the Papas. I was drawn to the gender-bending vocals of Cream’s Disraeli Gears (fall of ’67; discussed here). Both of us were dumbstruck by Bowie in 1972. Aston saw Bowie’s April 14, 1972 performance of “Starman” on Top of the Pops: Bowie’s “arm slouched around [guitarist Mick] Ronson’s shoulder as they sang the heavenly chorus.” I had no benefit of any alien visuals when our local freeform radio station in Boulder, Colorado played Ziggie Stardust from beginning to end, repeating the LP’s penultimate “Suffragette City,” stunning me since the station wouldn’t play the same song twice in a month.

Aston would go on to fall in love with several of my own favorite singer-songwriter-experimenters: Van Morrison, Robert Wyatt, Laura Nyro, Tim Buckley, Nina Simone, Portsmouth Sinfonia (Gavin Bryars’s orchestra for non-professionals, including Brian Eno), and John Grant, who grew up (partly) in the Denver metro area where I now live.

With this new volume, Breaking Down the Walls of Heartache: How Music Came Out, Aston fills a much needed lapse in LGBT+ pop history. Unlike books such as Zoot Suits and Second-Hand Dresses (1988) edited by Angela McRobbie and John Gill’s Queer Noises (1995), the former which deals with the subject tangentially and the latter which deals with it personally and sporadically, Breaking Down the Walls of Heartache (taking its name from a late ’60s Northern soul hit) moves decade by decade through the 20th century (a bit before, and after), just as the music itself comes into play.

Full disclosure(s): I am mentioned in the book’s Chapter 9 (dealing with the 1980s)[3]In regard to my band Age of Consent, Aston emailed me in December 2015 asking for an interview but it came the day of a job deadline and was overlooked. Nine months later he reached out again … Continue reading but, alas, am only able to review the first six chapters, ending with the ’60s. If this math doesn’t add up, so rich is Aston’s chronicle he spends two chapters dealing with the ’70s!

Finally, my only real quibble with Breaking Down the Walls of Heartache concerns occasional omissions of sources. As the son of a fine genealogist and as a writer myself who relies on sources old and new, more than once I’ve questioned authors who make assertions that have piqued my interest only to be told that the documentation behind them is not at hand. Not so with Martin Aston; in the single instance where I knew enough to question a passage with no footnote, he was able to supply the source. In any case, by merely naming the names of artists and their repertoire in the wide world of LGBT+ music, Aston provides future students of the subject the means for pursuit.

Crazy Quilt

It’s appropriate that Aston begins Chapter 1, partially titled The Art of Secrecy, with his description of Jonathan Caouette’s promo video for John Grant’s “Glacier,” which itself begins with still- and motion-pictures of late 19th- and early 20th-century men-with-men and women-with-women colliding with lurid headlines. Figures at World War are juxtaposed with warriors in warm embrace as well as denial-of-service rubber stamps alongside Nazi death camps. Camp (the other sort) clips abound, like the Cowardly Lion being primped by Emerald City beauticians and a cross-dressing Bugs Bunny putting the make on Elmer Fudd, up against graphic childbirth education film footage. There is preyed upon, put upon, putting out, putting up, putting down, and pushing past. It’s a Gay Power mixtape that includes crazy-quilt shots of many musicians along the way—Judy Garland, Josephine Baker, Marlene Dietrich, Jane Russell, Joel Grey, Doris Day, Tim Curry, Lance Loud, Michael Jackson, Village People, Lily Tomlin, “Hedwig,” Genesis P-Orridge, Jobriath, Pussy Riot, Dickey Doo, Frank Ocean—most of whom make appearances in Breaking Down the Walls of Heartache.

As Aston points out, the video’s imagery is symbolic of Grant’s own struggle with his sexuality, substances, and sex itself. As a linguist and translator (albeit a scant one) Grant would have faced an obvious disconnect between striving for verbal veracity while at the same time stifling his own spirit—he was “deeply closeted within a deeply religious family in Michigan, a state where it seems as if there is a church on every block,” writes Aston. Just as the late psychologist James Hillman has written, that “the terrible traits of the father…initiate the son into the hard lines of his own shadow [so that] the son does not have to hide his share of darkness,”[4]James Hillman, A Blue Fire: Selected Writings by James Hillman (New York: Harper & Row, 1989), 120. Grant likens his everygayman’s pain to a glacier “carving out deep valleys,” “creating spectacular landscapes,” and “nourishing the ground.” Yet as I write these words it is only today that a star like Barry Manilow, just 25 years Grant’s senior, feels free enough to admit what we all had known seemingly forever (well before Manilow’s 2014 marriage to his manager Garry Kief was revealed in 2015). And “Glacier”’s imagery haunts, as last month a Chechen Republic spokesman replied in response to a report of the arrest and/or killing of up to 100 gay men, “You cannot arrest or repress people who just don’t exist in the republic.” The Art of Secrecy indeed.

The Sound of Lavender—the other half of Aston’s Chapter 1 title—begins at about the beginning, at least as regards ancient Greek lyric work created for song and as recorded on papyri retrieved from trash heaps and mummy wraps. Aston covers only Alcman of Sparta (seventh century BCE), one of several such lyric poets (including the better-known Sappho of Lesbos), but then Breaking Down the Walls’ primary time frame is not antiquity but rather the hundred years that precede our own decade. Aston cites an online source describing Alcman’s surviving magnum opus as “a hymn for a chorus of virgins in celebration of the marriage of two young women,” but my translation at hand by the late great polymath Guy Davenport (in his 7 Greeks) doesn’t support this characterization of what Davenport calls an “amazing” hymn to Artemis on the Feast of the Plow. Davenport was so absorbed by the hymn, he crafted four translations, from literal to musical to mythical to “the sparest possible faithful.” A fragment of the male Alcman’s testament to women-loving women:

Imagine her if you can. Her hair,

As gold as a Venetian mane,

Flowers around her silver eyes.

What can I say to make you see?

Aston, along with his cited historians, then skips ahead to the twelfth century CE, remarking that the revolution of that century’s polyphony itself “may have been written in a homosexual sub-culture,” at least at Notre Dame. Later in the chapter he quotes University of Virginia English professor Bruce Holsinger who posits “a constant link between polyphony and sodomy in the puritan tradition” after discussing how at least one music journalist perceives Schubert essentially to have outed himself through his Trout Quintet. That’s some substantial gaydar.

While Walt Whitman provided proof in his writing of a stateside “homosexual community” (U.S. capital penalties against sodomy having been relaxed beginning in 1786), as Aston writes, only a small sliver of folk tradition in Britain gives clues to AC-DC fluidity and more. But the listed titles are telling: “The Handsome Cabin Boy,” “The Dark Slender Boy,” “The Strapping Lad,” as well as the sole “lesbian saga” unearthed by Aston, “Bessie Bell and Mary Gray.”

Aston devotes a subsection to “The art of impersonation” and another to “The love that dared to sing,” the latter that includes a lead-up, naming Karl Heinrich Ulrichs (coiner of the term Urning), Karl-Maria Kertbeny (confounder of the Greco-Latin hybrid homosexuality), Adolf Brand (publisher of the first gay journal Der Eigene), and sexologist Magnus Hirschfeld. A song, “Das Hirschfeldlied,” commemorated a scandal described by Aston in fascinating detail—even greater than that which had befallen Oscar Wilde. With this intersection of the social and sexual and song, Aston hooked me and I craved more. “Das Kinseylied” perhaps?

In the Life

And just as I was entranced by Aston’s portrait of German precocity, he moved to Prohibition-era Harlem and the dialectic of libertines and the law.

The 1920s boom roared, but with no licit champagne to celebrate—except on the down low, where more than libations were on offer. Jazz was the soundtrack, and while trombonist Clay Smith might not have been an etymologist, his famous quote seems appropriate in this context: “If the truth were known about the origin of the word ‘Jazz’ it would never be mentioned in polite society.”[5]See, for instance, “Jazz Is a Four-Letter Word” at the Cambridge Dictionary blog. Brilliantly Aston makes the obvious point that we so often choose to ignore regarding imbibers and where their inhibitions, once inhibited, might lead them: “Almost everyone was now officially illegal, not just anyone who acted on the urge to sleep with their own sex, which won its own description—‘in the life’.” Those “in the life” are contrasted by Aston with the “repressed, class-conscious goldfish bowl of European upper and middle-class society.” And this is reflected in the music and in Aston’s descriptions of alt- venues of the time like “rent parties” and “buffet flats” that were memorialized in song by Count Basie and Fats Waller.

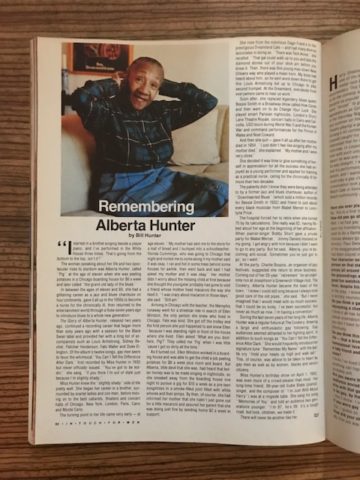

If some men still felt inhibited, as Aston writes, women performers felt doubly emancipated—from slavery and from their mandatory male mates on the road. Ma Rainey and Bessie Smith may be names we know, but Aston recounts how one mentored the other. I distinctly remember being gobsmacked by Smith’s “Give Me a Pigfoot and a Bottle of Beer” the first time I heard it, and Aston provides the backstory for this as well as citing other songs, beginning with those of Alberta Hunter, whose lyrics need no explication.

Men find mention, sometimes as nuanced writers or collaborators. “Tain’t Nobody’s Business If I Do” (also the name of this chapter) is first associated with Bessie Smith but was written by her “openly gay” pianist Porter Grainger. The titles and lyrics Aston provides for these artists—men, women, and those in between and outside—will have 21st-century readers Googling and YouTubing like Snopes-skeptics, astonished that anyone ninety years ago could have been so bold.

In Chapter 3 Aston reviews what had taken place in Europe, from drag acts to Germany’s two dozen-plus homosexual publications and cabarets as well as U.S. expatriate Josephine Baker and the British single “Masculine Women, Feminine Men.” The late ’20s saw May West’s hugely successful drama The Drag flop due to critical prudery but the film The Broadway Melody with its backstage setting and “snippy, preening queen” character won an Academy Award for Best Picture. La reine est arrivée it would seem as even Betty Boop’s real-life inspiration Helen Kane sang about how her male paramour was “so unusual,” in a song that Cindy Lauper covered (briefly) on her debut album five decades later.[6]On the same album, She’s So Unusual, Lauper referred to more sexual ambiguity in her cover of Prince’s “When You Were Mine,” in which she opts not to change the gender of whom she’s … Continue reading

As Aston points out, “publishers of sheet music insisted no lyric could be changed,” which led to some interesting juxtapositions such as Bing Crosby singing “There Ain’t No Sweet Man That’s Worth the Salt of My Tears” accompanied by whom Aston calls “the first (known) gay man of jazz,” cornet soloist Bix Beiderbecke.[7]Aston claims Beiderbecke as the composer of “There Ain’t No Sweet Man,” but it was written by Fred Fisher, as credited on this record label. All of this contributed to an actual “pansy craze” of the 1930s, but Crosby’s peers “pushed camp at the expense of machismo,” Aston writes, a tradeoff that on its face might not have been so bad. “Popular culture now allowed men to be effeminate, though the concept of masculine homosexuals would have been too threatening.”

Aston next turns to the practically-masculine Noël Coward and Cole Porter. Coward primarily was a dramatic playwright but his early musical productions contained some of his most popular songs. Among them likely is not “Green Carnation,” which Aston cites from Bitter Sweet (1929), referring to Oscar Wilde’s boutonnière-filler that twenty-five years later would morph stateside into a “green on Thursday” junior high school proscription.[8]My wife Andrea Carney has often recalled how her fellow junior high school students were called “queer” if they wore verdant vestments on Thursdays in the ’50s. “And as we are the reason/ For the nineties being gay/ We all wear a green carnation.” Aston then recounts how Coward’s estate contemplated its own prohibition of Tom (“Glad to Be Gay”) Robinson covering “Mad About the Boy,” perhaps Coward’s biggest hit, Coward having expressed the wish that his “female songs” not be rendered by men—publishers of sheet music be damned.[9]Coward himself wrote lyrics to the song from a male point of view for a New York production of Words and Music, from which the song comes, “though the management wouldn’t let him put it in as it … Continue reading Nevertheless we’re treated to a new gay lifestyle magazine—Aston credits it as the first ever—Bachelor, which did a profile of Coward in 1937.

As a married man (unlike Coward), Cole Porter was perhaps even more vicarious via his compositions. Yet he is credited by Aston as composing Broadway’s first gay love song in 1934: “You’re the Top.” If this might be questioned given that the song traditionally is sung as a back-and-forth by a woman and man (in either order), it is from a show called Anything Goes. The film version (1936) has Bing Crosby mouthing Ethel Merman’s lyrics as a ventriloquist’s dummy as well as doing a bit of camping; and the show’s plot does involve a beard. Also in 1934 “the first English lyric to feature the word ‘homosexual’” is named by Aston, with a royal tale behind it.

Aston moves on in Chapter 3 with much rich material and surprises. One particular drag venue in a city not even in the nation’s Top 40 is called by a writer “one of the first gay-positive communities in America, if not the first,” and so successful it took its act on the road.

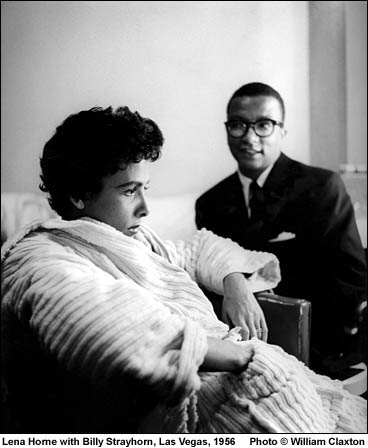

Aston closes the chapter with Billy Strayhorn who in the late ’30s had become to Duke Ellington what Bayard Rustin (himself a fine vocalist) would be to Martin Luther King in the ’50s. Strayhorn and Ellington’s first collaboration, “Something to Live For,” as rendered by Strayhorn and vocalist Ozzie Bailey (foregoing an introductory stanza), is a compelling compound of fleeting passivity, dawning drive and, yes, a hint of the decade’s suggestiveness—set in only ten lines.

Perfect Storm

Strayhorn appears in Chapter 4, but as the exception to what Bessie Smith biographer Chris Albertson, quoted by Aston, calls the “code of silence” of the time. Aston makes the case that within a jazz community that could have pushed lyrical boundaries regarding gender as it did other taboos, its participants hedged for the most part. Yet Aston mentions all-female jazz bands that “thrived” during World War II even as they were “shunned” by their male counterparts.

With a sketch of what made the perfect storm of the ’40s so consequential—e.g., WWII, the Kinsey Report, Gore Vidal’s The City and the Pillar—Aston reminds readers that the latter two were preceded by Lisa Ben/Edythe Eyde’s limited run of Vice Versa, a homespun periodical in Los Angeles for lesbians, which had its own music section. But it was bisexual and straight performers who more popularly reminded a public (as eventually outlined by Kinsey) what it already knew. Again Aston provides titles, lyrics, background, and—because the time period is more recent—actual reminiscences by later artists and writers who couldn’t help but be intrigued by songs like “Nature Boy.”

Aston’s section on classical composers of this period shows the fluidity of his subjects’ interests—musical (if not otherwise). The gamut of these composers, as diverse as Pauline Oliveros and John Cage to Samuel Barber and Benjamin Britten, might best be illustrated by Aaron Copland, who wrote everything from his anarchist anthem “Into the Streets May First”[10]Copland’s text is a poem by Alfred Hayes, who also wrote the words to “I Dreamed I Saw Joe Hill Last Night,” composed by Copland’s student Earl Robinson. See Robinson with Eric A. Gordon, … Continue reading to film soundtracks and the ballets Billy the Kid and Appalachian Spring to his own brand of twelve-tone works. But where Britten’s homosexual themes were self-evident, Aston makes the case for a more nuanced Copland.

This decade is bookended by Liberace, who began performing behind the curtain at Spivy’s Roof, whose eponymous proprietress sang naughty songs through the ’40s (and beyond). Adored by women, by the end of the decade Lee would be doing classical-pop mashups that took him nearly to the White House.[11]Aston claims Liberace performed for President Truman at the White House in 1950, but this is refuted by a Time magazine article (“Did Liberace Do DC?”, 29 May 2013). It may be that Lee’s … Continue reading

Midcentury Moderns

At this point in Aston’s tome we’re only on page 62 out of 535—and I’m at the 3000-word mark. Forty more pages are devoted to the ’50s (The Tutti Frutti Revolution), and seventy to the ’60s (Gay Party Pop and the Rock’n’Roll Closet).

Again, Aston places the musicians against the backdrop of that former decade’s purple purge, the commie-pinko-fag connection having been made by U.S. Sen. Joseph McCarthy (who asked Copland himself whether he’d engaged in sabotage but demurred on the question of sex) and aided by a complicit civil service. Among those profiled is Johnny Ray, famous first for his hit “Cry” and then for having pled guilty to soliciting an undercover cop months before. Ray was the subject of a Confidential magazine story in its second edition (April 1953), psychoanalyzing him, his histrionics, and his penchant for drag. Aston quotes author Jack Fritscher as saying that Ray’s perceived sexuality was discussed by people “who’d never whisper the word homosexuality.” Indeed Samuel Bernstein has argued that Confidential’s publisher “was actually a powerful if unwitting pioneer in the struggle for gay acceptance,” given that the outing that occurred in the magazine’s pages did nothing to curb careers but rather brought sex of all stripes above board.

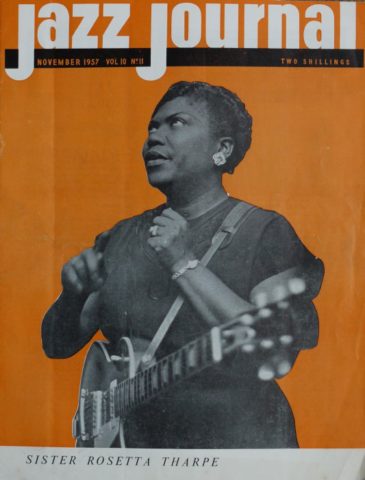

Aston provides informative musicology in this chapter, reminding readers that the godmother of rock’n’roll Sister Rosetta Tharpe was a same-sexer. (Since the posting of this review, Tharpe was inducted into the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame in the category of Early Influences.) Like so many others her roots were in the choir loft, which had a lot of closet space, as noted by Aston, only now being opened with the code of silence having been made moot by the deaths of the old-timers.

One of Tharpe’s fans, Richard Penniman, was kicked out of the house by his father; that and a lewd conduct sentence sent “Little” Richard on the road as Princess Lavonne, whose act employed elements of his idols. Including lyrics: his hit “Tutti Frutti” was inspired by Carmen Miranda’s “The Lady in the Tutti Frutti Hat,” and was given the drag act treatment with explicit rhymes that begin with “booty” but were bowdlerized in the booth. This began a series of, mm…, seminal singles, many of which had their genesis in his drag act. But, as Aston explains, Little Richard became remorseful, retreating to gospel at the decade’s end, returning only with reticence to the rock’n’roll he’d essentially invented.[12]I remember the late (gay) music critic Craig Lee’s consternation in his L.A. Weekly interviews with Little Richard and Pete Shelley (not together) when they both evaded the obvious. Since the … Continue reading

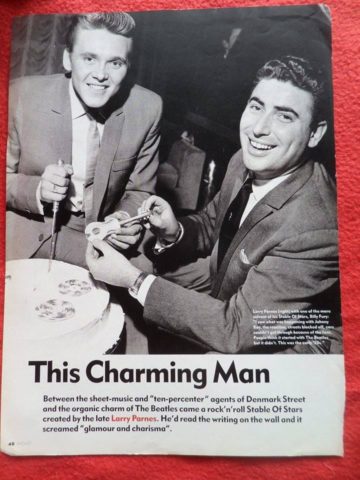

In the ’50s, talent managers were ascendent, with Larry Parnes becoming to music what Henry Willson already was to film. As Willson had done with Roy Fitzgerald—the future Rock Hudson—Parnes would do with partners and fellow Brits John Kennedy and Lionel Bart, reinventing and employing the remarkable surnames listed by Aston: Wilde (!), Steele, Fury, Eager, Pride, Gentle, Power, Fortune, Keen, Fame. Willson and Parnes each had a “stable” of working class heroes, soliciting (not always receiving) sexual favors in return for stardom.[13]Robert Hofler, The Man Who Invented Rock Hudson: The Pretty Boys and Dirty Deals of Henry Willson (New York: Carroll & Graff, 2005). I’m grateful to my friend George Copanas for this reference … Continue reading Decades later Larry Parnes would be the pattern for Harry Charms in film director Julian Temple’s liberal adaptation of the Colin McInnes novel Absolute Beginners, starring David Bowie, Ray Davies, and Sade.[14]D. Rimmer (!), “Beginners’ Pluck,” Rolling Stone, 05 Jun 1986. (Many managers and other behind-the-scenes movers also are discussed by Aston in his chapter on the ’60s, with Brian Epstein being only the most prominent.)

Aston continues with names familiar and obscure. Regarding the latter Aston offers up Baltimore’s Roc-A-Jets whose talented Jan Morrison was favorably compared with Patsy Cline even as she would be beaten up for refusing to dance with a man. Aston’s section on doo wop is only obscure in the revelation of the gay individuals whose songs and bands were household names.

As for the familiar, Elvis Presley covered “Hound Dog,” written for the gender-nonconforming Big Mama Thornton, by Leiber and Stoller, but lightened in tone for a blandly absurd version by Freddie Bell and the Bellboys, which Presley copied. Bleached-out as the lyric was, Aston asserts that Presley still felt it necessary to distance himself, explaining “that he was ‘putting down’ a friend rather than a lover.” The absurdity of Presley’s “Jailhouse Rock” can’t be excused however, since it was acted out on the big screen. Leaving aside what we know now about rape inside prison,[15]See this New York Review of Books article from late 2013. Aston points out that men even on the outside would not have been able to cavort with each other as they do on the inside in the song’s 1957 vehicle.

Television and Revolution

Aston begins his chapter on the 1960s, appropriately enough, with television. TV ownership had surged from 9% of homes in 1950 to 87% in 1960[16]Statistics cited from Cobbet Steinberg, TV Facts, New York: Facts on File, 1980. and Aston quotes late-show host Jack Paar as claiming that gays appeared to have done their own proliferating: “They are everywhere in television.” And they were on television, too, beginning with the documentary The Rejected (originally titled The Gay Ones), which aired September 11, 1961 in San Francisco and eventually on three fourths of the country’s 55 public television stations. Prior to airing, the documentary was cut from 120 to 59 minutes; trimmed was a scene shot at the Black Cat Bar whose entertainment emcee José Sarria issued the 1960 LP No Camping, which was bankrolled by an unlikely party, as Aston divulges.[17]Aston attributes to Sarria a passage from another documentary, Word Is Out (1977), regarding the practice of ending performances at the bar with “God save us nelly queens” (to the tune of “God … Continue reading

Marketing to an imaginary gay community began in 1960 with a trio of albums, and that story is as odd as the one behind the, er…, endowment for No Camping. Yet another venture, Camp Records, issued songs of the novelty sort. Regarding one title, Aston picks up on a pun lost on me, that “London Derriere,” is a “play on the Irish folk ballad ‘Londonderry Air’,” but he himself may have missed that “I’d Rather Fight Than Swish” is a riff on the U.S. cigarette ad campaign that eventually would employ Martha Stewart to utter its tag line, “Us Tareyton smokers would rather fight than switch!”[18]The slogan inspired at least two singles titled “I’d Rather Fight Than Switch” by The Tomboys (!) and A. C. Reed. As Aston relates, “among the hilarity” Camp included a “stab of realism” or three.

Aston mentions Lisa Ben’s 1960 same-sex parody of the traditional “Frankie and Johnnie,” issued as a fundraiser for her Daughters of Bilitis organization, which called her “the first gay folk singer.” As a preteen in Boulder, Colorado I remember browsing the record stacks of neighborhood friends’ parents and coming across racy discs by performers such as Rusty Warren who recorded a version of “Frankie and Johnnie” also in 1960 in which the two-timing man, killed by his female lover, is laid in his coffin in drag, apparently to further emasculate him (he‘d been shot in the crotch). Warren’s nightclub act was full of less overt, slyly feminist banter and balladry, moving in her monologues from the mundane to the undeniably inane, decrying double standards with a wink. In her signature number, “Knockers Up,“ the appeal to the “working girls” in her audience to go into the office the next day and “throw your shoulders back, [and] put a big smile on your face” to impress the boss would have been as obviously foolhardy then as it is today. Warren has been called the “Mother of the Sexual Revolution” according to her WFMU profile; despite such hyperbole she did dare to advocate sexual pleasure for women, a stance not lost on her male audience. Her first LP, issued in 1959, was called Songs for Sinners. Bottoms Up was issued in 1969.

Fifteen pages into The Sixties, Aston appears to have solved a nagging question. Decades ago my late musical partner John Callahan mentioned in passing about Otis Redding being gay, or something to that effect. Since then I had made a half-hearted attempt to follow up; now I wonder if John had a source.

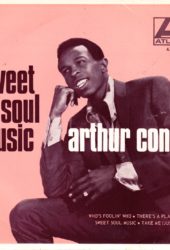

Aston explains how Redding had mentored Arthur Conley, who apparently was gay. Their collaborative hit “Sweet Soul Music” was released in 1967 when I was 11 or 12 years old, and for this white-bread boy the song was a primer I desperately needed since it “spotlight”-ed a half dozen soul artists. Redding died that same year, also the year of their meeting.[19]Conley was signed by Redding to his Jotis label in about 1965 without ever meeting the younger singer. The two finally met in 1967 when they plagiarized a performer they both loved, Sam Cooke, … Continue reading How that must have devastated Conley. Had Redding confided that early in his career he’d been a “Little Richard imitator” as included in a brand new biography?[20]Review of Jonathan Gould, Otis Redding: An Unfinished Life (New York: Crown Archetype, 2017) by Kirkus Reviews. The book contains eight references to Redding’s “impersonation” of … Continue reading Had Conley confided his own sexual orientation? Redding was a married man. He also spent a lot of time on the road. As ever (as my friend John would sign his missives).

If one had an operational gaydar in the ’60s, there was plenty to pick up on, as Aston chronicles. Selected titles: “Loneliness,” “Have I the Right?,” “Do You Come Here Often?”, “My Heart Has a Mind of Its Own,” “Where the Boys Are,”[21]Aston quotes the “Where the Boys Are”’s singer Connie Francis as calling it “the gay national anthem.” In 2006 John Grant covered the song with his band The Czars on the single Paint the … Continue reading “I Left My Heart in San Francisco,” “Crying In the Rain,” “Two Faces Have I,” “You Turn Me On,” “N-N-Nervous,”[22]These last two titles are by Ian Whitcomb whose LP Ian Whitcomb in Hollywood features a photo on the verso—likely unwitting—of the musician looking very much like a Selma Avenue hustler. “Walk Like a Man,” “Big Girls Don’t Cry,” “It’s My Party,” “You Don’t Own Me,” “You Don’t Have to Say You Love Me,” “The Girls Are at It Again,” “Twistin’ the Night Away,” “The Great Pretender,” “The Fig Man,” “Can’t Take My Eyes Off of You,” “You’ve Got to Hide Your Love Away,” “Miss Amanda Jones,” “See My Friends,” “David Watts,” “Dedicated Follower of Fashion,” “I’d Much Rather Be with the Boys,” “I’m a Boy,” “Uncle Bert,”[23]This title was by The Creation. Aston discusses the lyric that places Bert “with his trousers hanging down” at Hampstead Heath (to London what Griffith Park once was to Los Angeles). “Rumour … Continue reading “Something Strange,” “Kay, Why?”, “Run Run Run,” “Sister Ray,” “Lady Godiva’s Operation,” “Are You a Boy or a Girl?”, “Over the Wall We Go,” “She’s Got Medals,” “The American Way of Love.”

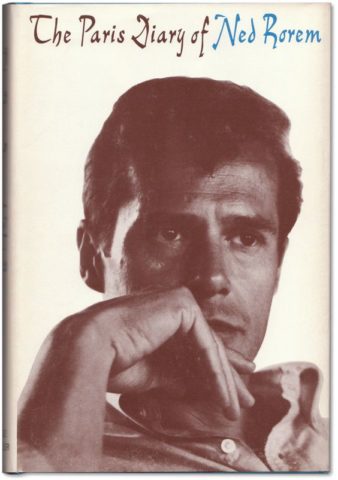

Aston fills out this chapter with stories about big names whose sexuality many of us take for granted but, like me, without particular foundation. I knew Long John Baldry had been out but not that he’d employed both Rod Stewart and Elton John. My mother and I collected all of classical composer Ned Rorem’s diaries, but I had no idea of The Paris Diary’s impact in 1966 as described by his (reprint) publisher, Da Capo Press:

The diaries marked the beginnings of gay liberation, not because Rorem made a special issue of his sexuality, but because he did not; rather, he wrote of his affairs frankly and unashamedly.

Poignantly Aston tempers that liberatory moment—in 1967 laws in the UK decriminalized contraception, abortion, and sodomy—with this:

Yet the secrecy, battened down by decades of guilt and fear, would mean no sudden defiant statement of pride in line with Nina Simone’s “To Be Young, Gifted and Black” to reinforce the on-going push for civil rights or even a race-related lament such as “I Wish I Knew How it Would Feel to be Free.”

If Aston’s ’60s chapter began with television, it ends appropriately with Revolution, the twain that were not supposed to meet according to Gil Scott-Heron. Aston mentions the 1965 (!) picketing of the White House by members of the Mattachine Society of Washington and Daughters of Bilitis against treatment of homosexuals in government, the 1966 “sip in” at a Greenwich Village bar protesting a discriminatory liquor law, the Compton’s Cafeteria “riot” that same year in San Francisco (subject of a film documentary), and the debut the next year of the late great Oscar Wilde Memorial Bookshop in New York as well as support organizations there and in San Francisco.[24]Omitted, understandably since it occurred in 1959, is the Cooper’s Donuts rebellion that I first found referenced in a sidebar of the post-liberationist anarchist pamphlet Towards the Queerest … Continue reading And, of course, Stonewall. Aston makes informed speculations on what could have been on the jukebox at the time of the initial raid.

One habitué of the Stonewall Inn—and its riot—profiled by Aston is Wayne/Jayne County who I first encountered on vinyl in the compilation Max’s Kansas City 1976, issued by the club of the same name whose inner sanctum, as Aston explains, was frequented by the Warhol crowd in the ’60s (just as they would the Mudd Club in the ’70s). County appears on that LP as Wayne—the assumed name being a play on the political division for which Detroit is the, mm…, seat—in full drag on the cover and inner sleeve. County’s song, also titled “Max’s Kansas City 1976,” is dedicated to Lou Reed. She is backed by the Back Street Boys (not that BSB) and the number pays tribute to burgeoning punk performers à la “Sweet Soul Music” by Arthur Conley; both County and Conley hailed from Atlanta. Aston delves into County’s rich back story leading up to Stonewall. I never would have thought of Wayne (later Jayne) County being the missing link between the fluidity-friendly hippies of the ’60s and the edginess of the ’70s. But come to think of it, an artist in my neck of the woods, Tomata du Plenty, essentially did the same thing, coming out of San Francisco’s Cockettes to front L.A.’s Screamers.

Pretty in Pink

It feels odd to end this review just before Martin Aston deals with the pivotal decade in perhaps both our lives. In 1973 at 17 I left Boulder for Los Angeles. One afternoon my first year there, likely in the San Fernando Valley, I remember having a sack lunch with acquaintances who had invited me in. They talked of “dressing up” that night and going to Hollywood. “Are you in theater?” I asked naïvely. “Something like that,” they answered. If eyes rolled, I was blind. Perhaps they sensed a kindred spirit in this teenager from Colorado, but too timid a one. Later I realized they were donning Bowie’s “satin and tat” and heading for the Sunset Strip. By the end of the decade I’d be dressing up myself. A favorite outfit: baby-blue bowling shirt with woman’s monogram, pink patent leather jeans, flat-heeled fence climber shoes. Don’t laugh; it got me into the Mudd Club.

I’m inclined also to recollect here something I can’t substantiate. Sometime before leaving Boulder, I recall a friend reading to me (or me to him) an item about a theretofore unknown band. “Throw out your Rolling Stones albums,” the writer declared, having just heard an LP by Little Feat. I’m tempted to say the same about my own little pop music library after reading Martin Aston’s Breaking Down the Walls of Heartache, except that, as with music, you never can have enough. So keep your LPs (I go to my shelves often only to find I didn’t!) and your books about this-core and that-core.

And by all means get—and keep—this one.

Text by David Hughes. © 2017 David Hughes. All rights reserved.