Wallace Thurman: Gay Impresario of the Harlem Renaissance

Two Reviews by Stephen O. Murray

September 12, 2000.

From the retrospect of 1939, Alain Locke, who had edited The New Negro, a path-breaking 1925 anthology, wrote: “It was the bright young talents of the [19]20s who went cosmopolite when they were advised to go racial, who went exhibitionist instead of going documentarian, who got jazz-mad and cabaret-crazy instead of getting folk-wise and sociologically sober.” A leader of the younger (than Locke) generation, who epitomized individualism and aspirations for producing art rather than uplift was Wallace Thurman (1902–1934).

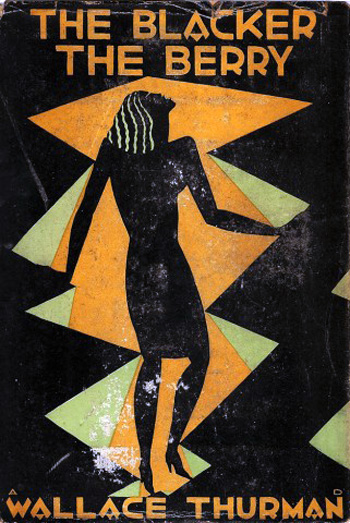

Reading Wallace Thurman’s Harlem Renaissance (1994) and Thurman’s best-known novel The Blacker the Berry (1929), I think that Thurman may be yet another writer whose life is more interesting than his writings.

Eleonore van Notten has done a formidable job of finding material on Thurman’s life and pointing out what is autobiographical (like three of the main characters in Blacker). In Blacker Thurman told more than showed, but it seems that he still produced an incisive analysis of the psychic costs of intraracial color prejudice.

It doesn’t occur to van Notten that Thurman’s sexuality might have anything to do with putting his experiences of rejection (by African Americans) for his blackness (and gaucheries) into the character of a woman (Emma Lou). I wonder if his desperation to be loved was as acute as hers, but embarrassingly effeminate. Better (in masculinity-adoring culture) to be Alva, the alcoholic libertine “sweetback,” who uses and misuses her. I don’t doubt that there is self-criticism in this portrait, and it is interesting that after fucking and fucking over his female alter ego, he has her finally leave him because he is cavorting with an effeminate male (seemingly not knowing how to bring his story to an end).

The naturalist writer was not comfortable with his own homosexuality. (The Bruce Nugent characters in Blacker are heterosexual, unlike in Infants of the Spring.) And Emma Lou flees a lesbian would-be supporter (p. 120). It would be hard to disagree with Alain Locke that Blacker is “exhibitionist in psychology” or with Du Bois that Thurman’s despising his blackness is not overcome by his analysis of the harmful effects of such views.

The naturalist writer was not comfortable with his own homosexuality. (The Bruce Nugent characters in Blacker are heterosexual, unlike in Infants of the Spring.) And Emma Lou flees a lesbian would-be supporter (p. 120). It would be hard to disagree with Alain Locke that Blacker is “exhibitionist in psychology” or with Du Bois that Thurman’s despising his blackness is not overcome by his analysis of the harmful effects of such views.

Van Notten is also on-target when she writes that “Thurman’s egoism, particularly as manifested in his Menckenite superiority, provoked social alienation rather than transcendence. Indeed, Thurman’s sensitivity to his social position of social outcast, which provoked his recreation as a Menckenite artist-iconoclast, exacerbated his isolation” and “Thurman’s understanding of alcohol as a stimulating and potentially self-destructive force is illustrated in Alva’s degeneration from a dynamic free-thinking pleasure seeker to little more than a carcass ‘wrecked from physical excess” (p. 233) and “Time and again Thurman stresses that the shared experience of racial oppression had not generated a homogeneous black race” (p. 223). He certainly put self-interest before race-loyalty and -uplift.

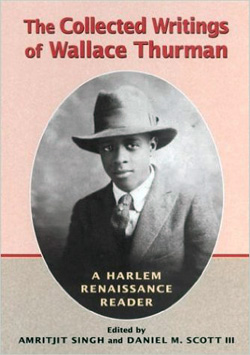

The Collected Writings of Wallace Thurman, edited by Amritjit Singh and Daniel M. Scott III and published in 2003 by Rutgers University Press, includes excerpts from the three published novels (totaling 42 pages from them). It also includes the two extant plays, Harlem (along with various pieces about its genesis and the story “Cordelia the Crude” in which the pivotal character was introduced) and Jeremiah the Magnificent. The latter is a very thinly fictionalized portrait of Marcus Garvey and the downfall of his Black Star Fleet that was supposed to take African Americans “home” to Africa.

In the original story, Thurman introduced Cordelia as follows:

Cordelia was a potential prostitute, meaning that although she has not yet realized the moral import of her wanton promiscuity not become mercenary, she had, nevertheless, become quite blasé and bountiful in the matter of bestowing sexual favors upon persuasive and likely young men.

This shows both that the extent of sexual liberation of even the most advanced “New Negroes” was not great and something of the vague and Thurman’s “dicty” phrase-turning. In addition to rent parties, a mother devoted to that “old-time religion,” and the sexual rejection of a member of the “Talented Tenth” that was raising up the race, there are number-runner gangsters and a frame-up that would not be out of place in another kind of noir.

Like Garvey, Jeremiah the Magnificent was ensnarled with mail fraud investigators and undercut by rapaciously self-enriching business associates (and, also like Garvey, traded in a loyal wife for a younger one before being deported). There is also a quite sympathetic, though bemused, essay about Garvey in a not previously published collection of essays about Harlem, Aunt Hagar’s Children (including the autobiographical “Notes of a Stepchild” and a piece on “The Negro Literary Renaissance”) that includes sympathetic biographical analyses of three “colored” leaders (the one on Garvey, plus and even-more-surprising (given how urban and avant-garde Thurman was) one on Booker T. Washington, and one on Frederick Douglas, who was less known and revered in the 1920s than he is now).

In addition to the often-anthologized “Cordelia the Crude” (from the legendary one issue of Fire!, which Thurman edited), there is one other short story (first published in 1926 in The Messenger). Some might consider “Grist in the Mill” as agit-prop, but I see it as another instance of Thurman’s sardonic take on race relations. It involves a transfusion of “black blood” saving the life of ultra-racial purist Colonel Charles Summers. When he found out “an inkly blackness enveloped him” as he “began to writhe and wriggle upon the floor” trying to rub off the internal taint.

There are about fifty pages of book reviews and literary essays. These include mixed reviews for Carl Van Vechten’s notoriously named novel Nigger Heaven, Langston Hughes’ poetry, and Rudolf Fisher’s Walls of Jericho, plus a survey of New Negro poets (Claude McKay receives the only unequivocal endorsement) and withering criticism of Quicksand, a very proper novel written by W. E. B. DuBois’ secretary, Jessie Fausset and of Du Bois’ advocacy of celebrating the black bourgeoisie rather than writing about low-down (and proto down-low) rural and urban life ways about which Du Bois was ashamed (“Negro Artists and the Negro”). The antagonism between Du Bois and the “niggerati” is partly explained in the book’s very academic introduction (slighting the sexual politics).

Although Thurman tried most literary forms, he was a lousy poet. There are only seven extant poems (and these are mostly extracted from letters to Langston Hughes). They fit on four pages. Thurman was a lively correspondent, and there are nearly 80 pages of letters from him (the plurality of them written to Langston Hughes). There are also 50 pages of essays published in various magazines about Harlem, including one on rent parties. (The play Harlem is mostly set during preparations for a rent party and ends during the party put on by Cordelia’s father, though significant action in it occurs in another apartment.)

Having read the two black novels (The Interne has only white characters and has long been out of print), I was most interested in the two plays and in essays relating to the literary politics. Thurman highly valued Claude McKay’s fiction, in addition to praising him as the best of the New Negro poets. Jean Toomer’s Cane is the only Renaissance novel Thurman was certain was a masterpiece. One of Thurman’s poets celebrates Toomer’s genius, and in “Negro Artists and the Negro” he wrote sarcastically of the Harlem vogue, among other ways in regard to the reception of Cane:

Cane was really pre-Renaissance, as it was published too soon to be lifted into the best-seller class merely because its author was a Negro. And, as Waldo Frank forewarned in his introduction to Cane, Jean Toomer was not a Negro artist, but an artist who had lost “lesser identities in the great well of life.” His book, therefore, was of little interest to sentimental whites or to Negroes with an inferiority complex to camouflage. Both the personality of the author and the style of his book were above the heads of these groups.

The edginess and frustration about being read for either documentary value or to provide “positive role models” run through Thurman’s writings about writers, including in the novel Infants of the Spring. In an oblique defense of that novel, he wrote:

Negroes, themselves, resent any novel, no matter how meritorious, which does not deal with what they call “the better class of Negroes.” Meaning the semi-literate bourgeoisie to whom keeping up with the Joneses implies doing nothing of which bourgeois whites might disapprove.

Thurman and his friends wrote about less refined Negroes and were castigated by “race men” leaders, especially Du Bois. Another example of Thurman’s sarcastic style is provided in this 1928 riff about Thurman’s bête noire (or from Thurman’s place on the color spectrum, bête jaune):

Dr. Du Bois is one of the outstanding Negroes of this or any other generation. He has served his race well; so well, in fact, that the artist in him has been stifled in order that the propagandist may thrive. No one will object to this being called noble and necessary sacrifice, but the days for such sacrifices are gone. The time has come now when the Negro artist can be his true self and pander to the stupidities of no one, either white or black.

The editors’ introductions to the various groupings of kinds of writings are very informative. Their introduction to the volume places Thurman in the context of views about the social construction of race, racial identity-formation (now and then), literary canon-formation, and the historical/literary discourses celebrating Harlem Renaissance writings and those attacking or dismissing them. Ways in which Thurman prefigured the rage and political incorrectness of Richard Wright are particularly foregrounded, along with Thurman’s particularly deep-seated feelings of otherness from blacks and white. (James Baldwin is not mentioned there, but is mentioned in the introduction to excerpts from the novels.)

The editors’ introductions to the various groupings of kinds of writings are very informative. Their introduction to the volume places Thurman in the context of views about the social construction of race, racial identity-formation (now and then), literary canon-formation, and the historical/literary discourses celebrating Harlem Renaissance writings and those attacking or dismissing them. Ways in which Thurman prefigured the rage and political incorrectness of Richard Wright are particularly foregrounded, along with Thurman’s particularly deep-seated feelings of otherness from blacks and white. (James Baldwin is not mentioned there, but is mentioned in the introduction to excerpts from the novels.)

It would have been useful to include a glossary of 1920s slang Thurman inscribed (such terms as “hincty,” “monkey-chaser,” and “four-flusher”). However, the chronology of Thurman’s life is helpful. And other than the rest of the three novels, the editors seem to have collected everything of any interest that Thurman published plus more than half of the contents of the collection that they published for the first time. Not all Thurman’s writing was top-flight, but almost all of it is includes interesting perspectives and observations of uneasy African Americans in the first third of the 20th century.

(For an overview of the Harlem Renaissance, see Steven Watson’s book, discussed here; and for its gay writers, see Gay Voices of the Harlem Renaissance, reviewed here.)

©2000, 2016, Stephen O. Murray

Originally posted on epinions 12 September 2000 and 3 February 2005