La Virgen de los Sicarios (The Virgin of the Assassins)

La Virgen de los Sicarios (The Virgin of the Assassins)

Directed by Barbet Schroeder

Written by Fernando Vallejo

Released September 20, 2000 (France)

Drama (foreign film)

101 min.

Review by Stephen O. Murray

October 11, 2001.

Filmed in the murder capital of the world, Medellin, Colombia, La Virgen de los sicarios (The Virgin of the Assassins), directed by Barbet Schroeder, has plenty of material to appall many viewers.

Showing man-boy love without portraying the man as a monster was sufficient to blind the critic of the ostensibly sophisticated New Yorker. The hair-triggers of the boys should frighten most everyone. The young killers’ devotion to folk Catholicism will scandalize some; the protagonist’s rejection of God may scandalize some others. There is no shortage of hair-triggered gangsters on film. And still others may find the alienated older writer a tiresome holdover from European art films of the 1960s. Nevertheless, I found the film riveting and important.

I don’t think it is giving away very much to say that La Virgen de los sicarios does not end with “And they all lived happily ever after.” Perhaps somewhat more surprising is that Fernando Vallejo (the writer gave his own name to the character both in his novel and in the screenplay he adapted from it), who begins the film by announcing that he has come back to Medellin to die, doesn’t.

I don’t think it is giving away very much to say that La Virgen de los sicarios does not end with “And they all lived happily ever after.” Perhaps somewhat more surprising is that Fernando Vallejo (the writer gave his own name to the character both in his novel and in the screenplay he adapted from it), who begins the film by announcing that he has come back to Medellin to die, doesn’t.

Very early on, Fernando also announces that he has had sex with more than a thousand males. Finding love is not on his agenda. For that matter, even finding more sex isn’t, but an old friend presents him a handsome, brooding youth named Alexis. They have sex, after which Fernando tries to pay him off, expecting nothing more, certainly not a committed relationship. However, Alexis clearly states that he is not interested in female partners (as many hustlers are) and goes along to the nearly unfurnished apartment Fernando has inherited. In the following days, he accompanies Fernando on a melancholy tour of sites from Fernando’s youth—at a time when Colombians went after each other with machetes instead of mini-Uzis. (In 1948 director Barbet Schroeder witnessed a decapitation in the streets there, when he was seven.)

Why does Alexis tag along with Fernando? He doesn’t have anything better to do and is amused by Fernando’s gallows humor and sarcasm about church and state—though both of them visit churches often (Alexis making the same weekly pilgrimage, Fernando touring many he remembers from his childhood).

Fernando is one of a long line of writers fascinated by handsome amoral juvenile delinquents (William S. Burroughs, Pier Paolo Pasolini, and Witold Gombrowicz seem particularly formative influences). Fernando and Alexis sleep together and presumably have sex, but on the screen they mostly walk around. Aside from any erotic thrall, Fernando is also fascinated by Alexis’s devotion to Santa María Auxiliadora (the particular Virgin Mary of the title, the patron of narco sicaros) and in Alexis as a typical young Colombian ready to shoot anyone who annoys them. Alexis guns down eight or nine men. Some of them were trying to shoot him, but he also blows away three fag baiters. That is, he embodies more than one kind of gay male fantasy!

Plot spoiler alert

In some ways Fernando is remarkable stupid. He fails to believe that Alexis must be armed and ready to shoot at all times. It is Fernando’s fault that Alexis is unarmed when he is gunned down (and still protecting Fernando). After a period of grief (I think it is supposed to be a year), Fernando goes out and finds a somewhat darker and maturer replacement (replacement lover, replacement killer). Fernando makes Wilmar into Alexis, as James Stewart replaced Madeline with Judy in Vertigo. In both instances, the replacement is fully aware of being turned into a reincarnation.

In some ways Fernando is remarkable stupid. He fails to believe that Alexis must be armed and ready to shoot at all times. It is Fernando’s fault that Alexis is unarmed when he is gunned down (and still protecting Fernando). After a period of grief (I think it is supposed to be a year), Fernando goes out and finds a somewhat darker and maturer replacement (replacement lover, replacement killer). Fernando makes Wilmar into Alexis, as James Stewart replaced Madeline with Judy in Vertigo. In both instances, the replacement is fully aware of being turned into a reincarnation.

The material goods Wilmar wants are nearly the same as what Alexis wanted. Fernando has plenty of money and buys Wilmar what he wants, just as he bought Alexis what he wanted. He made some attempt to refine Alexis’s tastes, but does not make any with Wilmar.

In both instances, concern for another (a wounded dog in the first instance, Wilmar’s mother in the second) is fatal. It is sentimentality rather than nihilism or brutality that gets them killed.

End plot spoiler alert

Conclusion

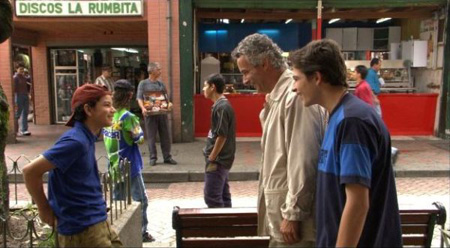

La Virgen de los sicarios has a very, very dark view of life on the streets for the very numerous poor youth of Latin America—in the tradition of Luis Bruñuel’s Los Olivados, Alejandro Gonzales Inarritu’s recent Amores Perros, and Hector Babenco’s Pixote. Besides casting the leading Colombian stage actor Germán Jaramillo as Fernando, Babenco cast two adolescents with movie-star good looks and Medellin street fatalism as his companions (Anderson Ballesteros as Alexis, Juan David Restrepo as Wilmar). Jaramillo tends to declaim, but this seems appropriate for a pompous upper-class writer feasting with panthers. The youths are totally convincing—chillingly convincing!

Although I don’t think the film is going to promote tourism to Medellin, the city (particularly from the apartment’s balcony) looks beautiful, and Jorge Arriagada’s score enhances the film. (The first Schroeder film I saw, The Valley Obscured by Clouds, was as much travelogue as romance—with a well-known score by Pink Floyd. His other cheery films include Idi Amin Dada, Barfly, Reversal of Fortune, and Straight White Female.)

Watching a morose writer who has returned to die wander through the hell of Medellin after the death of Pablo Escobar set various masterless young Colombian samurai shooting down each other is not everyone’s idea of a good movie, even if it is wonderfully photographed. Considering that America’s president has declared a new war (on terrorism) with the previous war (on drugs) an ongoing disaster, I think that contemplating fatalistic young males with no hopes for a good life is important. Those growing up in refugee camps don’t understand the rules of engagement of the Geneva conventions any more than do those in the slums of Medellin, and it seems to me that Bush, Cheney, et al. have no understanding of the enemy infantry in the wars on drugs or on terrorism.

published by epinions, 11 October 2001

©2001, 2016