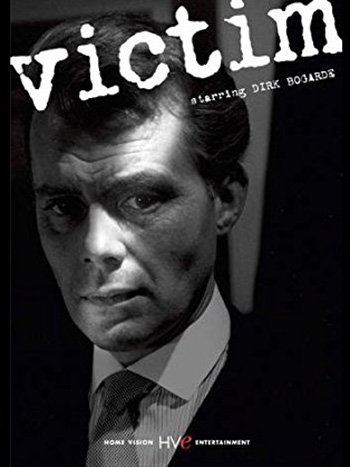

Victim

Victim

Directed by Basil Dearden

Written by Janet Green and John McCormick

Released August 31, 1961, in London

Drama (foreign: UK)

90/100 min.

Review by Stephen O. Murray

January 16, 2003.

Victim is a noirish thriller about blackmailing homosexuals when homosexual acts in private were illegal in the United Kingdom.

The movie was released in 1961, halfway between the Wolfenden Commission’s recommendation of law reform in 1957 and the 1967 law reform (also the year the first U.S. state, Illinois, decriminalized sodomy).

The film’s opening is reminiscent of Carol Reed’s (1947) Odd Man Out in which James Mason was on the run, and the film that launched Dirk Bogarde’s career, the 1952 Hunted, in which Bogarde was the hunted man on the run.

In Victim, directed by Basil Dearden (The League of Gentlemen, Khartoum), Bogarde plays Melville Farr, a barrister who is about to “take the silk” (become a Queen’s Counselor) and ducks attempts by a desperate youth, Jack Barrett [Peter McEnery], who has fled work at a construction site, taken a bundle from his lodgings, and sought help from various acquaintances to get out of the country.

Plot Spoiler Alert

It becomes clear that Barrett is homosexual, though he has at least one straight friend of his own age, Eddy Stone [Donny Churchill]. It is gradually revealed that it is not prosecution for homosexuality from which Barrett is fleeing, but rather prosecution for embezzlement. Detective Inspector Harris [John Barrie] is certain that the motive for the embezzlement is blackmail and that the blackmail centers on homosexuality. He says ninety percent of the cases of blackmail (there and then) do.

A compromising picture addressed to Barrett arrives at Stone’s, and Stone takes it to Farr, who at first thinks Stone is there to blackmail him. Instead they set out to find who the blackmailers are and to avenge the death (Barrett hung himself while in custody) of the young man they both failed to help in his hour of desperation. Stone and Farr figure out some other victims of the same blackmailers, and Mrs. Farr [Sylvia Syms] intuits and interrogates her husband to find out what is going on and what went on with Barrett (nothing physical).

End plot spoiler alert

The film, which has been digitally transferred to DVD with faultless clarity and a 1.66:1 aspect ratio, is an effective crime drama focused primarily on the victims of blackmail. The pained relationship of the Farrs is sensitively played. There are some heavy-handed (though not inaccurate) deliveries of messages about making criminals of homosexuals and the law serving as a charter for blackmail.

The police inspector seems too benign to be true, not interested in entrapping or prosecuting homosexuals and devoted to catching blackmailers. Farr is even more too good to be true. He’s like one of those Sidney Poitier physicians (No Way Out, Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner) who is hyper-accomplished, super-courageous, and saintly in a commitment to help others and in possessing the grace not be bothered by cheap shots. Indeed, in the role Bogarde plays a man who is going to “get the name without having the game,” that is, although he is homosexual in orientation, he has only had sexual relations with his wife (who knew of his feelings for men before marrying him and stands by her husband).

Director Basil Dearden and scenarist Janet Green had made another film, the murder mystery Sapphire, two years earlier focusing on blacks passing for white. The perils of passing to avoid social prejudices are also central in Victim.

A Janet Green play was also the basis for the 1957 movie with Dirk Bogarde as a junior Bluebeard in Cast a Dark Shadow, which was an earlier departure from his matinee idol career with some whiff of homosexual orientation, so the boundary between Bogarde’s later career of perverse characters (The Servant, The Damned, The Night Porter, Death in Venice, etc.) is not the decisive switch with Victim that it is sometimes presented as (and he played some dark-sided characters before appearing in Victim). Nonetheless, it was a risky choice of roles for a gay actor who had been invited to Hollywood to play Franz Liszt in director George Cukor’s Song Without End (1960).

And as tame as the representation of homosexuality is (there really is no representation of homosexuality, just frightened blackmailed homosexuals and a courageous champion who has never committed a homosexual act), it was reviled in its day, starting with some crew members. The film could not get an MPAA seal for American distribution, ostensibly for one utterance of the then-forbidden word “homosexual” (though, as Vito Russo pointed out in The Celluloid Closet, the MPAA had just allowed the word “faggotty” coming from the mouth of Sidney Poitier in Raisin in the Sun) and because “sexual aberration could be suggested but not spelled out” (an MPAA edict, 3 Oct. 1962). Time’s un-bylined movie critic was horrified:

What seems at first an attack on extortion seems at last a coyly sensational exploitation of homosexuality as a theme—and, what’s more offensive, an implicit approval of homosexuality as a practice. Almost all the deviates in the film are fine fellows—well-dressed, well-spoken, sensitive, kind…. Nowhere does the film suggest that homosexuality is a serious (but often curable) neurosis that attacks the biological basis of life itself.

Among the reviewer’s odd ideas is that the homosexuals shown are “fine fellows.” Most are portrayed as cringing cowards, though one might consider that their neuroses are based on fear of being blackmailed and/or imprisoned for loving other men. And as Pauline Kael (who knew something about not “curing” a homosexual man even by having his child) noted at the time, “Time should really be very happy with the movie, because the hero of the film is a man who has never given way to his homosexual impulses.” These are presented as being baser than his love for the very good woman who married him, and no one in the film is gay, though at the end Farr is going to accept visibility.

Victim went further than American movies were permitted to go into examining the consequences of sodomy laws and was part of a transformation in British films (homosexual characters also figured in A Taste of Honey, The Leather Boys, and The L-Shaped Room, the first two starring Rita Tushingham, the last Leslie Caron, during the early 1960s, and, a decade later, Peter Finch and Murray Head kissed in Sunday, Bloody Sunday).

Along with the historical significance of the film both in showing the mounting challenge to criminalization of homosexuality and in undermining the legitimacy of movie censorship, there is a pretty good crime/suspense movie within Victim, particularly the opening, the denouement, and a street meeting of blackmailer and challenger. The only better ones from Britain of the 1950s and beginning of the 1960s are blacklisted American director’s Jules Dassin’s Night and the City (starring Richard Widmark) and Midnight Lace, the latter also written by Green (for Doris Day).

The DVD includes a somewhat coy trailer and a half-hour interview of Bogarde just before the film’s release, which includes clips from some of his earlier movies.

first published by CultureDose, 16 January 2003

©2003, 2017, Stephen O. Murray