This Unknown Flesh: A Selection of Plays

This Unknown Flesh: A Selection of Plays

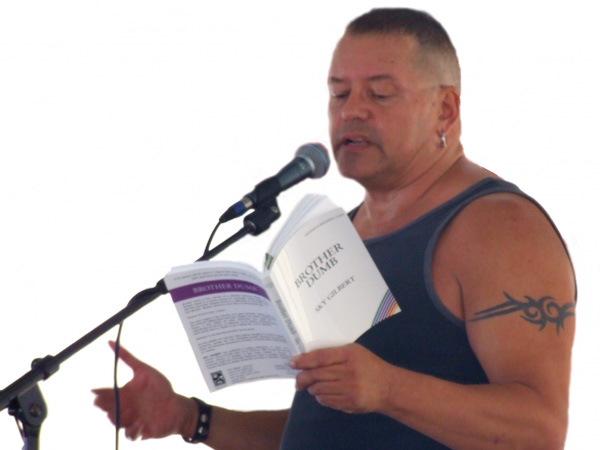

by Sky Gilbert

Published by Oberon Books

Published September 1, 2003

Theatre (plays)

233 pgs. • Find on Amazon.com

Reviewed by Stephen O. Murray

October 30, 2003

Sky Gilbert is a Toronto gay theater impresario (writer, director, sometimes actor, founder and long-time head of the Buddies in Bad Time Theatre), film-maker, and novelist whose work postdates my residence in Toronto. His outré memoir Ejaculations from the Charm Factory made me want to see some of the plays the productions of which he recalls in that book. It seems that I did have a chance to see him perform in his traveling hit show Drag Queens in Outer Space, but I missed it.

There is a prominent drag queen role in only one of the six plays (and the least of the six) staged between 1983 and 1994 that are collected in This Unknown Flesh. The other four feature famous gay writers. One portrays the aging and alcoholic playwright Tennessee Williams casting a polite Florida adolescent boy as an angel. Williams asks the boy to read a poem by Rupert Brooke and makes no attempt to touch him Although suffused with sadness, My Night With Tennessee could reasonably be characterized as “sweet,” not least in the boy’s nonjudgmental tenderness for the wounded elder.

“Sweet” is not an adjective that would occur to anyone seeing or reading the two plays about the Italian film-director/writer Pier Paolo Pasolini and the boy who killed him, Angelo Pedari, though Gilbert also has Pasolini seeing the boy as an angel, albeit an angel of death. The first, Pasolini/Pelosi or The God in Unknown Flesh: A Theatrical Enquiry into the Murder of Filmmaker Pier Paulo Pasolini focuses more on the death wish Gilbert attributes to Pasolini. Despite its title, the second, In Which Pier Paulo Pasolini Sees His Own Death in the Face of a Boy: A Defacement in the Form of a Play is more concerned with the society of repression and homophobia (specifically, male fear of being penetrated and liking it).

Both of these plays ignore the possibility (and widespread assumption) that Pasolini’s murder was planned by his enemies (and/or the many whom he had outraged in his openly pederastic lifestyle and in his obscene last film, Salo) rather than a spontaneous attack by a trick gone bad. I am quite aware that Gilbert was not attempting reportage documenting the murder. Indeed, the more hallucinatory first Pasolini play has Pasolini cradling the dying trick at the end:

When he suffers, I want to hold him [though] he is not someone I would like to know well…. He is what you last want to see.

In the second Pasolini play, it is that the open homosexual wants to penetrate the straight-identified hustler that sets off a murderous rage. Gilbert’s Pasolini character says that “it is not so much because I long for death,” but never articulates what it is instead that excites him about boys he knows are dangerous and in whose eyes he sees his own death. (There is also a parallel drama in which Gracious provokes Goodness to murder him.)

Hester is a very short (six-page) scene in the dressing room of a drag queen responding to knocks on the door, about which I have nothing to say/write.

Theatrelife is an elaborate play about a contemporary theater company mounting a Victorian melodrama. Sexual politics (heterosexual and homosexual) are central and the artificiality of theater heightened by the mounting of a very old-fashioned play. Reading it, it seems that it would be very entertaining on stage.

It is hard to gauge, though, the theatrical effects that Gilbert strives for in all these plays from reading them. Robert Wallace’s introduction asserts (and elaborates considerably upon):

The primary effect of Sky Gilbert’s work for the theatre is the transformation of the audience from isolated consumers of theatrical entertainment to collective participants in oppositional art.

This is attained not only with multiple layers on the stage but by moving the actors into the audience on a number of occasions.

The final play in the collection, More Divine: A Performance for Roland Barthes shows two internationally renowned social/literary theorists from the College de France, Roland Barthes and Michel Foucault (both of whom died during the 1980s), competing for an attractive male student, Olivier, circa 1980. The diffident aesthete Barthes is thwarted and jealous as Olivier is captivated (or captured) by the more aggressively sexual Foucault (who, like Gilbert’s characters Tennessee Williams, Pier Paolo Pasolini, and Geoffrey, the ringmaster of Theatrelife, see young men as angels to be cherished).

Skipping over another set of characters in the usual second narrative, Barthes goes to North Africa and finds solace with Arab youth. Foucault arrives and chides his colleague for “emotional domination” and “classism.” They go on to discuss shame and coming out, and then Barthes has a scene of bitter recriminations aimed at an astounded Olivier. The play ends back in Paris with the audience joining in something akin to the procession at the end of Fellini’s 8 1/2. How it works in a theater filled with Torontonians (whom I found to be very cold-blooded when I lived there a few years earlier), I don’t know. Even on the page, however, More Divine is an interesting and highly theatrical experience. (It also fits with what I know of Barthes and Foucault.)

There is frequent provocation for thought about sex and death in these plays. Having read them, I’d especially like to see More Divine and Theatrelife staged. For reading, My Night with Tennessee and More Divine are the most outstanding of the plays collected herein.

The volume is enhanced by inclusion of photos from Buddies productions and by Robert Wallace’s introduction.

published on Associated Content 30 October 2003

©2003, 2016, Stephen O. Murray