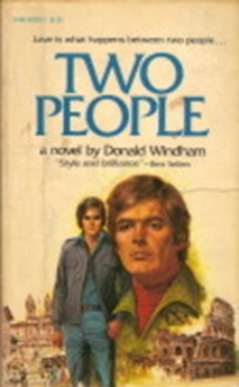

Two People

Two People

by Donald Windham

Published by Coward-McCann

First Published 1965

Mondial Gay Classics edition: February 13, 2010

Fiction

194 pgs. • Find on Amazon.com

Reviewed by Stephen O. Murray

March 8, 1995

Although I don’t really trust the verisimilitude of either main character, and find the resolutions too pat (verisimilitude would be for Marcello not to be able to get to a last meeting), I like Donald Windham’s Two People.

The blurbs from E. M. Forster and Tennessee Williams are a bit extravagant, but the one from Truman Capote—as “evocative” as Death in Venice with “often truer” insight of its renunciation—would be popular now for rejecting “categories.”

The book features love between a heterosexual 34-year-old American (Forrest), whose wife has left him, and 17-year-old Italian (Marcello), who has “no special desires” (p.41), “no hint of limitation or perversion…promiscuous encounters are to Italian boys what ice cream sodas at corner drugstores are to their American counterpart” (Latin object undifferentiation—p. 12).

The book features love between a heterosexual 34-year-old American (Forrest), whose wife has left him, and 17-year-old Italian (Marcello), who has “no special desires” (p.41), “no hint of limitation or perversion…promiscuous encounters are to Italian boys what ice cream sodas at corner drugstores are to their American counterpart” (Latin object undifferentiation—p. 12).

Discretion about who did what to whom was necessary then (1965). Being clear that they “made love” was daring then, especially since neither dies, a fate that seems mandated for representations of homosexuality on screen or between book covers in the 1950s and ’60s.

The chapters alternate between Forrest’s point of view and Marcello’s, and I find both credible. Forrest is also doing desultory research on Giordano Bruno, the sixteenth-century scientist (and Dominican friar) who was burned at the stake by the Inquisition for refusing to renounce the heresy of the earth orbiting the sun. Nothing remotely as dramatic happens to those engaging in practices “not to be named among Christians,” but commonly occurring in Italy since ancient times, as a friend reminds Forrest.

In responding to the notorious homophobic critic Stanley Kauffman dismissing it as a “sex novel” (seemingly because two males in it have a sexual relationship, however ungraphic its portrayal is—the same way that movies with no nudity or graphic sex are routinely rated “R”) Windham wrote:

I have deliberately used sex only as the key that unlocks the door to my subject and tried to make this clear by not writing about it from a psychoanalytic, moralistic, or pornographic viewpoint? I chose a sexual situation that is usually treated in one of these ways specifically to underline the fact that I am treating it matter-of-factly.

As Philip Gambone wrote in The Lost Library, “Those looking for hot scenes of passionate man-boy sex will not find it here. If you read the novel too quickly, you could almost miss the references to the times Marcello and Forrest go to bed.”

The book contains evidence of “the will not to know” about what male family members may be doing with other males (“don’t ask, don’t tell”): including a Sicilian saying that to speak little is a virtue (p. 231) and “there was no point in talking about a thing that was not known and could not be changed” (“Bell’arti parrari picca,” p. 251), along with Marcello’s failure to ask questions or supply personal information (though willing to describe what others do, p. 33, p. 232).

Quotes such as “Roman boys like to see new reflections of themselves in foreigners, not the same ones that they get in their mirrors at home” (p. 45); “He is crazy, Marcello thought. But he answered the question as though it had some meaning” (p. 119); and “He had wanted to enter the boy’s life, but he had only managed to draw the boy a tiny way into his own” (p. 192) fit with my view of interculture, though.

8 March 1995

©1995, 2016, Stephen O. Murray