Trio

Trio

by Dorothy Baker

Published by The Riverside Press

Published 1943

Genre (subgenre)

234 pgs. • Find on Amazon.com

Reviewed by Stephen O. Murray

December 4, 2004

(plot spoiler warning)

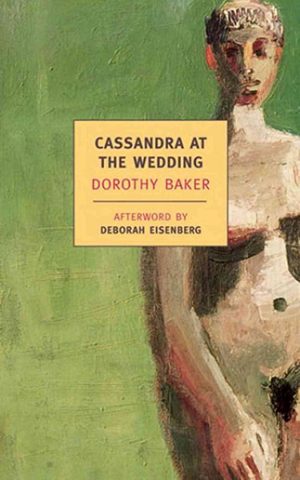

I think that New York Review Books has chosen wisely which books by Dorothy Baker (1907–68) to reprint: her pathbreaking first novel about an obsessive jazz trumpeter, Young Man with a Horn (1938), and her last, a tale of the title character attempting (not necessarily consciously) to undermine her sister’s wedding, Cassandra at the Wedding (1962).

There is a whiff of lesbian feelings undermining the marriage of the trumpeter in the first one, and Cassandra’s wish to continue her monopoly of her sister’s intimacy in the latter seems homoerotic to me. There is no homosexuality in either book. For that matter, there is none in Baker’s “lesbian novel,” Trio, which was first published in 1943 and was then adopted by Baker and her husband Howard for the New York stage, from which it was driven off for its immorality the next year.

Cassandra is a Berkeley graduate student, as was Janet, the flighty central character in Trio. The university is not specified, but the eucalyptus grove, as well as Baker’s long residence in Berkeley, makes it certain that it is the French Department of the University of California, Berkeley in which Janet is the assistant to charismatic professor Pauline Maury, who has ascended to a named chair for her brilliant analysis of late-19th-century “decadent” poets—Baudelaire, Rimbaud, Verlaine.

Cassandra is a Berkeley graduate student, as was Janet, the flighty central character in Trio. The university is not specified, but the eucalyptus grove, as well as Baker’s long residence in Berkeley, makes it certain that it is the French Department of the University of California, Berkeley in which Janet is the assistant to charismatic professor Pauline Maury, who has ascended to a named chair for her brilliant analysis of late-19th-century “decadent” poets—Baudelaire, Rimbaud, Verlaine.

The setting of the first scene/chapter is a tea party in Professor Maury’s chic apartment. Janet plays assistant host, and Ray MacKenzie has been hired to help out. After Pauline drives a doddering senior female faculty member home and is inveigled into having dinner with the woman, Janet goes off with Ray.

The second scene/chapter is set in Ray’s subterranean apartment. Janet has fled another tea party (turned cocktail party after the staid elders left) to Ray’s. She has been sneaking off to there with some frequency. Not realizing that Janet is something of a slave beloved of Pauline Maury, Ray attempts to convince Janet to marry him—right away. Pauline arrives to take Janet “home,” ready to arrange an abortion if Janet is pregnant by the young stud. (Ray is nominally a student at the same university, but more interested in photography and acting.)

Janet has been trying to tell Ray something about why marrying her is impossible. She avers that she does not love Pauline Maury but has been more than a professional protégé of the older woman. Ray is shocked, indeed sickened, that his beloved is in a lesbian relationship. (It is not explicitly named that, and the (homo)sexual content is wholly elided.)

Like the first scene, the final one is set in Pauline’s apartment. Janet is packing to go home (to Arizona) when Ray, having overcome his initial horror, arrives to take her away from filth and depravity.

Pauline Maury is on the verge of being disgraced for nonsexual reasons (though it seems an earlier sexual relationship was involved) so that her suicide has more motives than that of Janet’s incipient flight (though pity for the shaken woman-lover has caused Janet to change her mind, again, and stay with her professor).

Pauline Maury is not portrayed as particularly butch, though Janet is femme, not least in ceding making decisions about her career and life to the older woman. (The fear of the exclusively lesbian that her partner will be taken away by a man is widely reported in butch/femme pairings, especially before the 1970s.)

In 1940s (and later) American novels, any character who is visibly homosexual must die, preferably from self-disgust. In Trio the homosexual is Pauline Maury, who has dominated Janet. Janet does not have a particular sexual orientation; she exhibits passivity, whether to male or female dominators.

Although the “deviance” was not named and there was no sexual content, the stage version of Trio was sufficiently shocking that moralists (primarily ministers) campaigned to get the play shut down in New York in 1944—even with heterosexuality triumphing in the end. Maybe they did not like that Pauline Maury’s suicide had a motive other than disgust at her homosexual feelings and (failed) relationships. In fact, though frustrated at (another) failure of a mentor/protégé relationship with an attractive younger woman, Pauline Maury does not denounce her feelings/nature.

Though the text fills only 150 pages, I found reading the book something of a slog (especially in contrast to her absorbing first and last novels). The middle (heterosexual romance) scene drags on until Professor Maury shows up and Ray is clued in that Janet is (has been?) a “pervert.” (I think he decides she has been a largely innocent victim of a predatory patroness, though he is puzzled that Janet cannot break free, even after deciding to shuck her academic career and discard what she has written of a dissertation. Baker does not have him deliver his analysis, so there is not solid textual support for my interpretation.)

I don’t see how either woman could be a “role model,” even in a time with no positive representations of lesbians. (Patricia Highsmith broke the mold, albeit under a pseudonym, with The Price of Salt in 1953.)

Baker wrote that she had been “seriously hampered by an abject admiration for Ernest Hemingway,” and her writing was generally terse (and dialogue-heavy) with little dallying in psychological analysis of her often self-destructive characters (including the entirely heterosexual young man with a horn who drinks himself to death at the age of 30.)

4 December 2004

©2004, 2016, Stephen O. Murray