To the Friend Who Did Not Save My Life

To the Friend Who Did Not Save My Life

by Herve Guibert

Published by Quartet Books

Published November 1, 1991

Fiction (memoir?)

252 pgs. • Find on Amazon.com

Reviewed by Stephen O. Murray

April 20, 1994

In the auto-fictional novel À l’ami qui ne m’a pas sauvé la vie (which won the Prix Colette in 1990), Hervé Guibert (1955–91) wrote of buying time with AZT (zidovudine)[1]3TC/Lamivudine was approved by the FDA on 17 November 1995 for use with zidovudine (AZT) and, not until 2002, as a once-a-day dosed medication. This was written before 3TC or any of the protease … Continue reading to write more books.

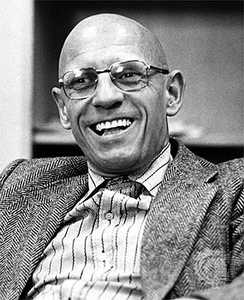

I had thought that Michel Foucault was the “friend” in the title To the Friend Who Did Not Save My Life, but the title seems to refer to the American entrepreneur Bill rather than to Muzil, the character based on Foucault. Muzil could have but seemingly chose not to know he was dying of AIDS. He also was maniacally finishing various books.

I had thought that Michel Foucault was the “friend” in the title To the Friend Who Did Not Save My Life, but the title seems to refer to the American entrepreneur Bill rather than to Muzil, the character based on Foucault. Muzil could have but seemingly chose not to know he was dying of AIDS. He also was maniacally finishing various books.

The narrator has the strange idea that “taking AZT as long as one can tolerate it” means to just before death. Actually, some people die still taking it, but many cease to tolerate (and/or cease to benefit by it) earlier. I guess that DDI and DDC weren’t available in France in 1990.

There is also an interesting sense of shared blood so that Jules and his wife and children are doomed together by shared substance (the same HIV, but Hervé conceives shared blood as the pathogenic substance rather than a virus in their blood (p. 194).

I like the matter-of-fact tone even about lurid or morbid fantasies. Guibert had the famed French lucidity lacking in Foucault (who was glib but somewhat Germanic in density (and sentence length).

What spoke most directly to me is “Adolescence is a sickness. When I’m not working I relapse into adolescence” (p. 202). What doesn’t resonate at all is that AIDS is “a disease that gave death time to live and its victims time to die, time to discover time” (p.164). There are many slow deaths (all in my view hideous: I want to be healthy or to be dead). And I have not “discovered” time through being infected. I feel that I am wasting time, but I don’t experience its passing.

“Lost between our lives and our deaths” (p. 141) is more like how I feel: less clarified than lost and bewildered. And the unconcern about who knows (first in justifying writing about Muzil’s illness (p. 91), later in knowing that what he wrote will soon be all over town (p. 185). I spat out at [Paul] Rabinow that Foucault died in the closet about AIDS (though outed by Guibert, whose family could not cover it up posthumously, as Foucault’s tried to).

©1994, 2016, Stephen O. Murray

written 20 April 1994, later published on epinions