Three Hashiguchi Ryosuke Films

by Stephen O. Murray

January 23, 2006.

Hatachi no Binetsu (A Touch of Fever/ Slight Fever of a 20-Year-Old, 1993, directed by Hashiguchi Ryosuke, 2.3/5 stars) is a visually static portrait of two young Japanese hustlers, the gal pals of each, and the infatuation of one (Endô Masashi as Shin, the more feminine, less successful prostitute) for the other (the affectless Hakamada Yoshihiko as Tatsuro, the more successful prostitute). It is filmed in long static shots (nearly as long and static as in Hou Hsiao-Hsien and Tsai Ming-Liang movies). Hashiguchi’s (2001) Hush is a much, much better film of somewhat similar materials involving anomic young Japanese gay males and their female admirers. (I don’t remember it being as visually static, and Hush has characters I remember better after more than a year than I did Fever’s a day after watching it.)

Nagisa no Shindobaddo (Like Grains of Sand, 1995, directed by Hashiguchi Ryosuke, 3.2 /5 stars) is a far-too-long (129 minutes) melodrama about Japanese high school students falling painfully in unrequited love.

Nagisa no Shindobaddo (Like Grains of Sand, 1995, directed by Hashiguchi Ryosuke, 3.2 /5 stars) is a far-too-long (129 minutes) melodrama about Japanese high school students falling painfully in unrequited love.

Like Hashiguchi’s (1993) Touch of Fever, the movie, the scenes, and the shots are overly long with lots of pointless “dialogue” (if one can use that for talking past auditors) and attractive semi-clad adolescent Japanese males on languid display. (In Fever the youths simulated sex. In Grains there is a kiss, but mostly medium shots of looks of longing.)

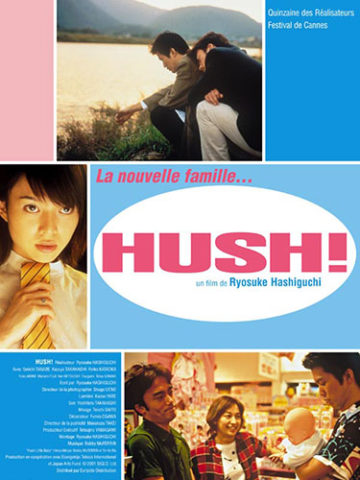

Getting Things Together

The 2001 comedy/soap opera Hush! (4/5 stars) is very confusing at first. It runs two and a quarter hours with some scenes that go on too long and jumps abruptly, leaving the audience to impose a time scheme. Some of the shot set-ups are questionable and many are held at Ozu-like length. Despite the alien rhythm of the movie and differences between what Japanese audiences find funny and what I find funny, I gradually figured out who the main characters were and came to find them engaging. I am especially interested in how Japanese gay men cope with a highly regimented society with very narrow (Confucian) expectations about the duty to perpetuate the male line.

Hush! shows somewhat greater ability (or willingness?) to recognize that a son/brother might be gay (and the word itself is used and understood by the characters, replacing the pejorative labels current in Okoge). The mother of the more butch and reticent gay male partner, Katsuhiro (Tanabe Seiichi) is convinced that he will have his male genital equipment removed and have breast implants, but the man’s niece, aged around ten, has a more matter-of-fact sense that gay men who do not want to be women exist. Moreover, Katsuhiro’s brother (the girl’s father, Shoji, played by Mitsuishi Ken) is accepting and somewhat discomfits Katsuhiro when he tells him that Katsuhiro’s sexual orientation is no surprise to him. (Katsuhiro is unpleasantly surprised that his orientation is obvious to several characters, after tentative attempts (at different times) to come out to two co-workers in a boat-building enterprise fail.)

Hush! shows somewhat greater ability (or willingness?) to recognize that a son/brother might be gay (and the word itself is used and understood by the characters, replacing the pejorative labels current in Okoge). The mother of the more butch and reticent gay male partner, Katsuhiro (Tanabe Seiichi) is convinced that he will have his male genital equipment removed and have breast implants, but the man’s niece, aged around ten, has a more matter-of-fact sense that gay men who do not want to be women exist. Moreover, Katsuhiro’s brother (the girl’s father, Shoji, played by Mitsuishi Ken) is accepting and somewhat discomfits Katsuhiro when he tells him that Katsuhiro’s sexual orientation is no surprise to him. (Katsuhiro is unpleasantly surprised that his orientation is obvious to several characters, after tentative attempts (at different times) to come out to two co-workers in a boat-building enterprise fail.)

His partner, Naoya (Takahashi Kazuya), works in a pet store/dog-grooming business, and is more open about being gay (though he also has a mother whose understanding of what being gay might mean is rather far off the mark). The movie starts with a trick leaving Naoya’s apartment and Katsuhiro has moved in with Naoya between scenes, leaving the audience guessing how long they have been living together when two women (separately) throw themselves at the polite but remote Katsuhiro. One is a shy and delusional coworker) named Yoko (Kurita Yôko). The other, Asako (Kataoka Reiko ), is a sexually experienced (in her doctor’s nastily censorious view, promiscuous) dental-crown maker who is fed up with selfish straight men and decides she wants to have Katsuhiro’s child. Not that she knows him! She knows that he has a male partner and that he is considerate because Katsuhiro gave her an umbrella after hers had been stolen in a restaurant where Katsuhiro and Naoya had also been lunching.

Katsuhiro is not much given to discussing intimate matters with anyone, and is understandably startled by being asked if he is engaged to Yoko (one of Yoko’s delusions), asked if Naoya is his life partner (which he acknowledges with a gulp and some chagrin at being cased out so easily as gay in the restaurant). Asako then informs him that she wants to have his baby. Not to have a relationship with him, not to have sex with him, but to use his sperm to fertilize her. The basis for this choice, she announces, is that he has “father eyes.” I would imagine that Katsuhiro’s eyes are bulging at this point, but there is not the close-up one would expect. He does not know what to say, but does think about the idea of paternity.

Recalling Ang Lee’s The Wedding Banquet more than a little, Naoya first blows up when he learns of the proposition, but then becomes a pal of Asako (though plenty irritated that Katsuhiro is not more brutal to Yoko’s delusions of a romance). There is a very formal family visit that I find hilarious (compensating for not getting some of the humor Japanese see elsewhere?). Naoya, Katsuhiro, and Asako are all seemingly petrified as Katsuhiro’s brother-in-law and Naoya’s mother denounce Katsuhiro—not for his gay relationship but for being unfaithful to Naoya with two women. (Yoko has sent them a dossier on Asako’s disreputable past that included at least one suicide attempt and two abortions, and restating her view that Katsuhiro is engaged to marry Yoko.) Katsuhiro is again mortified, though the scene is especially interesting in contrast to the family conclave in Okoge.

There are more bumps in the road (including a way-too-long scene of the three on a river bank) before an entertainingly if conventional happy ending (though it, too, has something of a twist). Having reached it, I went back to watch the first ten minutes again. That this was necessary reflects a lack of ability on the part of the director Ryosuke Hashiguchi to communicate information the audience needs, but that I was willing to spend more time indicates that I eventually cared who the characters were and how Naoya and Katsuhiro first met (and who was riding to work on a bicycle rather insecurely locked before and after the ride…)

There are more bumps in the road (including a way-too-long scene of the three on a river bank) before an entertainingly if conventional happy ending (though it, too, has something of a twist). Having reached it, I went back to watch the first ten minutes again. That this was necessary reflects a lack of ability on the part of the director Ryosuke Hashiguchi to communicate information the audience needs, but that I was willing to spend more time indicates that I eventually cared who the characters were and how Naoya and Katsuhiro first met (and who was riding to work on a bicycle rather insecurely locked before and after the ride…)

The movie has an unusual but engaging soundtrack by Bobby McFerrin. There are several scenes of male derrieres (including the one sex scene with the very brown one of a brash heterosexual male with Asako. I missed the character’s name, but he is very funny in each of his four scenes) and more in which the characters are clad in underwear (plus one with Katsuhiro leading a water aerobics class in a fetching Speedo).

The first two capsule reviews were published on epinions 23 January 2006

The review of Hush! 5 January 2005

©2005, 2006, 2016 Stephen O. Murray