Harry Hay: A Voice from the Past, a Vision for the Future

Harry Hay: A Voice from the Past, a Vision for the Future

by Mark Thompson

as published in Gay Spirit: Myth and Meaning

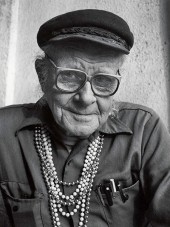

The HIC is grateful to Mark Thompson and White Crane Books for permission to publish this historic essay. This material is copyright protected and may not be reproduced without permission from the author and publisher. Image by Robert Giard.

Full of complex memories from a eventful life and, at seventy five, quick to point out that he is still living it, Harry (Henry) Hay commands a unique place on the American scene. Generally acknowledged as the contemporary “father of gay liberation,” Hay carries a vision as radical as it is simple. Using terms such as the gay window, subject-subject consciousness, and a separate people whose time has come, Hay holds forth the ideas that gay people embody a form of consciousness as different from the mainstream’s as their sexuality and that they have a special contribution to make to humanity. Although, he stresses, gay people must determine for themselves what this perspective might be.

Full of complex memories from a eventful life and, at seventy five, quick to point out that he is still living it, Harry (Henry) Hay commands a unique place on the American scene. Generally acknowledged as the contemporary “father of gay liberation,” Hay carries a vision as radical as it is simple. Using terms such as the gay window, subject-subject consciousness, and a separate people whose time has come, Hay holds forth the ideas that gay people embody a form of consciousness as different from the mainstream’s as their sexuality and that they have a special contribution to make to humanity. Although, he stresses, gay people must determine for themselves what this perspective might be.

Hay’s conception of Mattachine in the early 1950s—the first successful attempt to organize homosexuals politically in America—is recounted at length in the following chapter. The society’s rise, development and ultimate betrayal of Hay was to change profoundly not only the course of one man’s life but the path taken by a major political and social movement as well. During the past thirty-five years, Hay has continued to live a life dedicated to social reform on many fronts, sharing much of that time with his life partner, John Burnside, whom he met in 1963. Still, the essential questions that first ignited Hay’s imagination have been left largely unresolved, submerged by a movement’s struggle for rights and power:

- Who are we gay people?

- Where have we been throughout the ages?

- What might we be for?

Hay and I first met in spring 1979. The pretext was to help spread the word about the Spiritual Conference for Radical Fairies, and the interview included here was the result of that meeting. Hay seemed larger than life at the time, history personified. Experience of his humor, his foibles, and his residing strength of character has made him more human to me since, making the depth of his convictions all the more real.

Knowledge of themselves and the world they inhabit has always seemed best passed on personally, one-to-one, among gay men. Hay excels in the role of gay storyteller, and one tale he tells about himself illustrates this point well.

In January 1930, at the age of seventeen, Hay enticed a man fifteen years older than himself in Los Angeles’s notorious Pershing Square.

The guy I seduced into picking me up and bringing me out into the gay world had himself been brought out by a guy who was a member of the Chicago Society for Human Rights.

The society, says Hay, was basically a social group that had a short and abortive life in the Midwest city during the mid-1920s.

The idea of gay people getting together at all, in more than a daisy chain, was an eye-opener of an idea. Champ passed it on to me as if it were too dangerous; the failure of the Chicago group should be a direct warning to anybody trying to do anything like that again.

The germ of an idea was planted, nevertheless. It was a warning not heeded, and half a century later, the dream that gay people have a right to know who they are has effectively been passed on to yet another generation. It is a dream made all the more remarkable by the scope of Harry Hay’s vision.

Historical Overview

May Day, 1979

A minority has its own kind of aggression.

It absolutely hates the majority—not without cause, I grant you. It even hates the other minorities, because all minorities are in competition: Each one proclaims that its sufferings are the worst and its wrongs are the blackest. And the more they all hate, the more they are persecuted, the nastier they become! Do you think it makes people nasty to be loved? You know it doesn’t! Then why should it make them nice to be loathed? While you’re being persecuted, you hate what’s happening to you, you hate the people who are making it happen; you’re in a world of hate. Why, you wouldn’t recognize love if you met it! You’d suspect love! You’d think there was something behind it—some motive—some trick…

—Christopher Isherwood, A Single Man

I set aside my copy of Isherwood’s great novel and gaze at the clouds passing by the window. I’m on an early morning flight to Los Angeles, to meet a man who—without my knowing—will awaken a lifetime of dreams that, until now, have been elusive as the mist that floats just beyond reach.

Harry Hay is not a name recognized by most gay people. Yet, two decades before Stonewall thrust the need for gay civil liberties into national focus, Hay had already established the foundation from which these rights could be declared. Hay’s pioneering efforts helped point the way to the thousands now coming out to families, in demonstrations and in the media across the country.

Hay announced his sexual orientation to friends at Stanford University in October 1931, at the age of nineteen. Even then, he realized that asserting oneself politically was not a full definition of gay liberation. Being a homosexual, he felt, meant more than just equal rights and privileges. It was a “gift” allowed to a certain percentage of humanity, offering a different set of biological, social and spiritual receptors through which the world could be perceived and interpreted. Whether this innate difference could be fully accepted and understood was another matter altogether, as Hay was later to discover.

Hay’s vision has been informed by an amazing range of life experiences: He has been an actor, a Marxist organizer and teacher, an expert musicologist, a prolific writer, and Indian rights activist and an outspoken advocate for other progressive causes.

Born in England on April 7, 1912, he moved shortly after the outbreak of World War I to the Chilean Andes, where his father managed Anaconda copper mines. His parents returned to their native America in 1916, however, bringing their children to Los Angeles, where Hay was to spend most of the rest of his life.

Although he came from a privileged background, Hay was exposed to liberal ideas and causes from an early age. As a teenager, he worked in the fields of western Nevada during the summer, where his Wobbly coworkers gave him International Workers of the World tracts to read at night, testing him on them by day.

At home, he was tutored for a while by a Jesuit priest in the history of religion and philosophy toward the idea of recruiting him into the Jesuit order. He later studied in a Los Angeles lawyer’s office for a year and by the end of 1930 was ready to continue his education at Stanford University, where he impressed the faculty with his precocious political insights.

(Among other whom he impressed was fellow student James Broughton. Although the two men entertained a brief friendship, they would not meet again until fifty years later at a gathering for radical fairies in the Colorado mountains.)

During the depression years, Hay worked in the theater, giving his first performance in 1932 at the Hollywood Playhouse. His imposing manner, both on and off the stage, earned him the title “The Duchess.”

Within a year, Hay met fellow leftist actor Will Geer. Their two-year romance made an indelible impact on Hay, as Geer taught him street theater, exposed him to Hollywood’s extensive gay subculture, and introduced him to the Communist Party. Hay would maintain contact with the Party for the next twenty years, earning a reputation as an effective teacher and organizer.

In 1938, Hay married another party member and adopted two daughters. But his relationship to wife and party was increasingly strained as Hay became interested in organizing homosexuals. By early 1950s both commitments had come to an end—but were not forgotten. In July 1955, Hay was called before the House Un-American Activities Committee and successfully withstood questions about his earlier Communist associations.

Momentarily putting aside the facts of Hay’s personal history, it is not at all unlikely that Southern California would give birth to the modern gay movement in America. Although there had been earlier attempts to organize homosexuals and there were known gay communities in the nation’s major cities, particularly after World War II, the Mattachine Society was the first ongoing gay political organization in the United States. Los Angeles has always displayed a propensity for nurturing idealists and visionaries of many kinds. It is the West, after all, a social frontier less bound by convention, well tempered by the special historic and natural elements that have formed its open character.

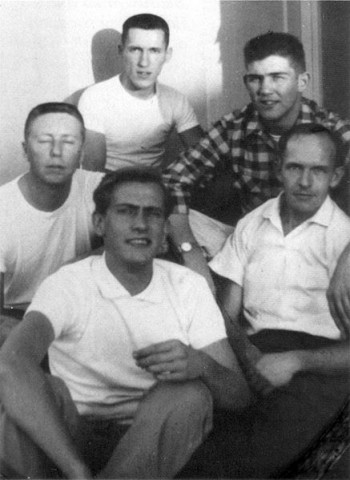

As reported in Jonathan Katz’s landmark Gay American History, Hay used the word “androgynous” to describe the nation’s gay minority when he first conceived the need for organization in 1948. The idea slowly grew during the months that followed, a time marked by escalating national paranoia. In July 1950, war broke out in Korea, and with Rudi Gernreich, Hay’s first recruit, he collected five hundred signatures for the now-famous Stockholm Peace Petition on two strips of Santa Monica Bay known locally to gays as their beaches.

Hay and Gernreich also planted the idea for a gay organization, and while few committed themselves to action, some names and addresses were collected. This list later became the basis for the Mattachine Society’s first discussion groups in December 1950 and January 1951.

A surviving report from one of these early meetings quotes Hay stating that “sexual energy not used by homosexuals for procreation, as it is by heterosexuals, should be channelized elsewhere where its ends can be creativity.”

In fall 1951, Hay realized that organizing the Mattachine “was a call to me deeper than the innermost reaches of spirit, a vision quest more important than life.”

In spring 1952, one of the original members [Dale Jennings] was arrested by the Los Angeles vice squad on the charges of soliciting an officer to commit a homosexual act. The member denied the charge, and the society came to his defense.

It was an important case. The jury deliberated forty hours and, with the exception of one member, voted straight acquittal. The case was dismissed, and for the first time in California history and admitted homosexual was freed on a lewd-vagrancy charge.

While a resounding precedent had been established for gay rights, the event also marked the beginning of the end of Hay’s original vision for the society. The group attracted many new members and began to assert itself politically. Questionnaires were sent off to candidates for an upcoming Los Angeles city election asking, among other points, if they favored guidance programs for young people beginning to “manifest subconscious aspects of social variance.”

The media began to report on this “strange new pressure group,” and inevitably the Communist and liberal political leanings of some of the group’s early founders and supporters started to become an issue. Hay explained that “we had been getting in this status-quo crowd … they had to get control of that damn Mattachine Society, which was tarnishing their image, giving them a bad name. This is when the real dissension began between the founders and the middle-class crowd.”

In April 1953, a convention was called in a Los Angeles church. Two hundred gay people attended, many of them delegates from other groups newly formed throughout the state. It was the first time in the history of the United States that such a congregation gathered.

“You looked up, and all of a sudden the room became vast,” said Hay.

He addressed the convention with a long speech designed to answer charges of Communist influence over the group and “to reiterate the foundation’s aim to consider itself strictly nonpartisan and nonpolitical in its objective and in its operation.” But Hay realized, even then, that the original dream was gone.

The original society was based upon the feeling of idealism, a great transcendent dream of what being gay was all about. I had proposed from the very beginning that it would be Mattachine’s job to find out who we gays were and, on such bases, to find ways to make our contributions to our parent hetero society.

The society after 1953 was also established in other cities around the country but primarily concerned itself with legal change, “with being seen as respectable—rather than self-respecting.”

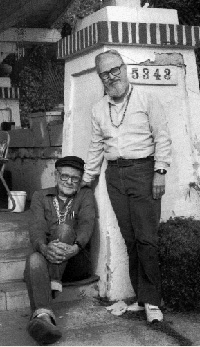

The convention marked the end of Hay’s principal involvement with the group. He set off alone—and later with Burnside and a few close friends—to continue to explore the significance of his original questioning.

I was one year old when Hay left the organization he conceived and founded. By the time I came out in the early 1970s, membership in the society had dwindled, its purpose having been subsumed into a larger context of events.

Like most gay people of my generation, I came to a full awareness of my sexuality during a time when political activism, feminist consciousness and freedom to explore alternative beliefs were established motifs in our culture. Yet the question asked by Hay over thirty years before—“Who are we?”—still remains relatively unexplored. It is a question still left unanswered within me.

Hay was waiting in a small apartment in West Hollywood. He and Burnside had recently arrived from New Mexico, where they have lived the past ten years, to help organize a spiritual conference for gay men in the Arizona desert. But future visions are built on acknowledgment of the past, and that is where Hay and I begin.

continue to the interview…