Homosexual Themes in Cinema

Homosexual Themes in Cinema

Part 2 (continued from part 1)

by Lee Atwell

Tangents Vol. 1 No. 7

March 1966

Originally printed in the April 1966 issue of Tangents, pp. 4–9

Part 2: England

Not long after the Wolfenden Report went into circulation, two films appeared in England, both based on the events surrounding the trial and imprisonment of Oscar Wilde.

Ken Hughes’ The Man With the Green Carnation, enjoyed a richer, subtler interpretation of the Wildean era, with a wider appeal than the intimate and probing Trials of Oscar Wilde, directed by Gregory Rattoff. Both films follow the record documents of the trial accurately, with key scenes very similar in staging, if interpreted differently. Peter Finch’s Wilde, while convincing as a dramatic portrayal of great finesse and power, nevertheless lacks the immediate physical identification and understanding that Robert Morley gives to Oscar. The difference lies in the fact that Finch is essentially a sophisticated modern, whereas Morley projects the tortured Romantic Victorian that we feel is more like Wilde. As for the character of Lord Alfred (“Bosie”) Douglas and his relationship with Wilde, John Fraser’s performance in The Man With the Green Carnation captures all the arrogance and aristocratic bitchiness, the dandyish savoir-faire that is lacking in John Neville’s corresponding role. Consequently, in the Morley film we never glimpse the real power that Alfred exerts over Wilde and which is the source of his downfall.

If both these films are lacking as examples of film art (aside from some fine acting), their impact was as can be imagined, mildly shattering, since for the first time a film had dared to deal exclusively with a homosexual character, albeit a respectably married man and an artist to boot. Without bowing to the conventions of “discretion,” both films placed before society a human tragedy for which it was responsible, and which raised certain moral issues about the regulation of individual rights….

Of perhaps more immediate effect was Michael Relph and Basil Drearden’s film Victim, critically hailed as an innovation in that it was the first British film to concern itself with the lives and problems of homosexuals. Although an effective piece of propaganda for the Wolfenden plea, it must be said that Victim does not succeed very well as a film. Disguised as a blackmail melodrama, the movie shifts between emotional tension and reportage, even while drawing some fine performances and defining some of the agonizing personal conflicts that threaten to destroy the homosexual from day to day. Farr, a successful barrister [Dirk Bogarde], feels guilty about the death of a young construction worker, Barrett [Peter McEnery] with whom he has been involved. A blackmail ring threatens Farr’s exposure, and the boy commits suicide after trying to contact Farr. Most of the film involves Farr’s tracking down the blackmailers who prey on homosexuals. Here we get a tactful glimpse of the London homosexual underworld, but with the tone of a detective thriller in place of authenticity. In place of the usual camp talk and behavior are the photos of muscle men and statues of David. Clues? On the other hand there are moments of strong emotional tension. Barrett (probably the first non-stereotyped, real homosexual in a movie) tries desperately to solicit help from his acquaintances—straight and gay—when Farr fails him, and later, in the moments prior to his death one senses a profound tragic pity for this boy, for this single man. Farr, finally admitting to himself that he loved the boy and feeling a real sense of loss, movingly confesses his hidden desire to his wife, a fact which she must painfully accept.

The pros and cons of the law are injected throughout without becoming overly didactic, but the strongest hit is made when Farr and his wife close their garage door one morning to find the words, “Farr is Queer” scrawled on the surface. Peter Baker’s commentary in Films and Filming is timely and apt.

Victim, for all its faults, is a landmark in British Cinema. The British have stopped being hypocrites and the censor has indicated that no subject, responsibly treated, is taboo. And when, as inevitably will happen, the law is changed and a man is no longer penalized for expressing his senses and sensibility as he will, Victim will have made its contribution to that understanding. And we’ll have to find a new name for “queer.”

Tony Richardson’s film A Taste of Honey is a lyricized interpretation of Shelagh Delaney’s play, in which the director sees his characters as innocents, reflecting the resilience of the human spirit in faee of a chaotic and meaningless world.

Here, the homosexual character, Geoffrey [Murray Melvin], an effeminate vagabond who befriends and mothers Jo [Rita Tushingham] the pregnant schoolgirl, passes beyond the level of an affected stereotype to a vital, human, if, at times, pathetic character. Jo finds her “taste of honey,” her moments of mad joy and later a kind of love with the sensitive yet uninhibited Geoff, who can only relate to her because she has genuinely accepted him and needs him. Geoff is an “obvious homosexual,” and this is accepted as a matter of fact from the beginning: when Jo rather slyly inquires about the nature of his sex life (What do you do?) he squirms uneasily and is immediately inclined to retreat. But she takes a liking to her new “big sister.” Situations like these succeed throughout the film because of the director’s sense of humor and his enormous affection for this couple, real, yet elevated to a poetic intensity.

One of the most striking aspects of the treatment of homosexual characters in British films is that in most instances there is an individual, accepted and defined as a unique human type, rather than as a social or group representative. Rather than presenting an offensive type (as Richardson does with Rod Steiger in The Loved One) for caricature effect, the emphasis is on portraying a character with whom the audience can identify in order to counteract any uneasiness or disgust the audience might normally harbor toward such an individual. This is the case with Barrett and Geoff, as it is with Pete in Sidney Furie’s The Leather Boys.

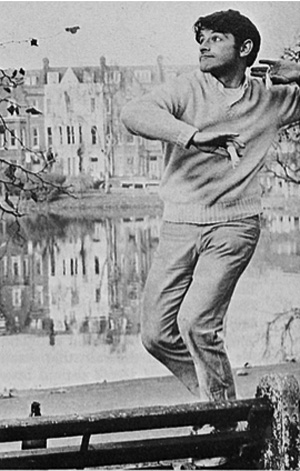

Taking for its milieu the leather-cycle cult in Northern England, Furie’s film is an unusually perceptive study of the development and tragic dissolution of a friendship between two young cyclists. The younger, Reggie [Colin Campbell] is drawn to Pete [Dudley Sutton] after separation from an absurd mismatch with Dot [Rita Tushingham] his loud, irresponsible, fun-loving teenage bride. Reggie turns to Pete for a more reliable companionship, a figure of conviction, compassion and acceptance. Peter Harcourt, in Sight and Sound, accurately finds Pete: “extravagantly conceived: a jovial extroverted prankster, with arms open wide in loving acceptance of the world he wanders through, yet with dark glasses and a leather jacket that help to hide the loneliness within. It is in the creation of this character, and of his observed love for Reggie, that the central distinction of the film can be found.” With some astute observations—not to speak of his disregard for women—Pete can be seen to have some definite homosexual mannerisms, but as so often in life, these are obscured by better surface qualities. It is not until Dot senses the nature of Pete’s feelings and suggests that they look like a couple of “queers,” that Reggie begins to have doubts about Pete and perhaps even himself. He is still too inexperienced with life to be sure of his own feelings or of his relationships with others so that, when his suspicions about Pete are confirmed by some queens in a local pub, he can only withdraw, shocked, afraid, hurt.

The most recent outstanding homosexual characterization in a British film is Ronald Curran’s performance as Malcolm in John Schlesinger’s Darling. This film is so full of rich characters, not the least being the eupeptic Julie Christie, that we encounter Malcolm almost in the flash of a moment, appropriately. In the course of Diana’s amorous peregrinations, she finds herself attached to a young English photographer, who subsequently skyrockets her to fame as a model. He is quietly introduced in an amusing shoplifting outing with Diana, and we sense an immediate camaraderie between the two, but it is not until their excursion to Capri that we are made aware of Malcolm’s homosexual inclinations. He pointedly cruises an attractive waiter at the beach, and that evening keeps a rendezvous with him. The following morning, Diana, irked at being left alone, reproaches him as a “traitor,” and to even the score, sleeps with the same waiter that night. Diana finds a rare but transitory happiness and affection with Malcolm, and in a weaker moment even proposes that they get a palazzo on the coast, declaring “I can do without sex…don’t like it very much anyway.” Diana loves Malcolm because her relationship with him entails no real responsibility or emotional tie: Friends but never lovers remains the creed. Ronald Curran’s performance is remarkable in that he is utterly charming and spontaneous, like a character out of a musical revue; yet his vitality is matched by realism. His campy joie de vivre is also tinged with certain sadness and tenderness…and as Princess Diana moves on to an Italian count, Malcolm smiles contentedly, sunning and devouring grapes on a pleasure yacht.

A number of other British films have dealt in some degree with homosexuality, either as a contingent aspect of the plot or as a strong underlying psychological motivation in character relationships.

In David Lean’s Lawrence of Arabia, the account of Lawrence’s capture by the Turkish general [Jose Ferrer] is interpreted as a sadistic homosexual encounter. When the general surveys his captives, caresses Peter O’Toole’s bare white chest, and stares into his baby-blue eyes, his intentions are obvious. The rest is legend, and as to the meaning of the beating Lawrence receives, one can speculate on various theories.

The film version of Becket, like its theatrical counterpart, is a study of the complex emotional, psychological, and spiritual interplay between two men, Thomas Becket and Henry II. The paradoxical character of both men is evident, especially in Henry, whose coarseness and brutality are complemented by a tenderness and vulnerability in the presence of Becket. O’Toole’s virtuoso performance is rich in color and wit as well as neurotic sensitivity. The qualities which Burton gives to Becket complement the deficiencies we see in Henry. This forms the central conflict in their intense love-hate relationship. The homosexual theme takes the form of a sublimated neurotic obsession on Henry’s part, and he is constantly reminding Becket that he has never really loved him—except as his King, and O’Toole’s desperate, hysterical declarations of love are voiced in passionate defense of a declared enemy.

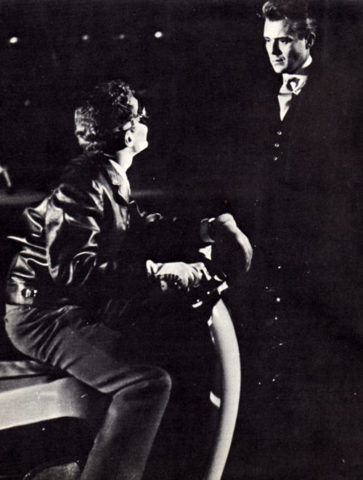

Similar, although not so obvious overtones are prevalent in Joseph Losey’s The Servant, from a screenplay by Harold Pinter based on Robin Maugham’s novel. Here, our interest is directed toward the ambiguous relationship between Tony, a young upper-class dandy [James Fox] and his shrewd but overly efficient servant, Barratt [Dirk Bogarde]. The film traces the slow undermining and corruption of Tony by Barratt and his mistress until the roles of servant and master are psychologically reversed. The oblique undercurrent of unconscious homosexual attraction is sustained from the opening interview—in Fox’s slightly strained love scene with fiancee, Wendy Craig; in various manifestations of jealous regard for Barratt who takes ample advantage of his weaknesses. When all else is stripped bare, and the two men are face-to-face, reduced to playing childish drunken games, Barratt taunts Tony by accusing him of “having a guilty conscience,” after he confesses that he is lost without his dear friend. The sexual implications of their roles are confirmed by Losey, who believes that all strong male relationships contain some element of homosexuality, even if not manifested overtly.

In Lindsay Anderson’s This Sporting Life, homosexual allusions crop up as a part of the natural fabric of the sports world. Frank Machin (played by Richard Harris), an aspiring Rugby champ, is politely pursued by a wealthy promoter—whose wife has seduced him—and is accused by his landlady of an unnatural friendship with an elderly gentleman admirer. American audiences were somewhat taken aback by several bathing scenes in which players are seen romping playfully bare-assed in an indoor pool. It is significant that Machin’s only really meaningful human contacts are with other men, on the Rugby field, or wrestling in the shower room.

The kind of malicious and destructive attitudes that are passed off by society onto children can he observed in Philip Leacock’s minor masterpiece, Reach for Glory (1962), which, although financed by Columbia Pictures, has yet to receive a national release in the U.S. The film deals with conflicts between city and country boys in a rural school during war time in a kind of social-psychological macrocosm a la Golding. Two young boys, who find common interests and a much needed companionship, embrace in a moment of genuine innocence and are thereby accosted and accused of physical love-making by a group of older boys.

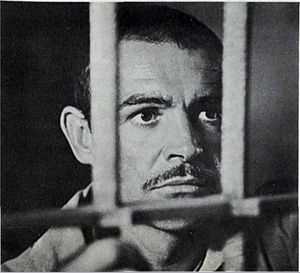

The impact of this kind of enmity in adult life is seen in Sidney Lumet’s study of a British military prison, The Hill. One of a group of prisoners under sentence is Stevens, assumed a homosexual on the basis of some letters to his wife, by “Staff” Williams whose petulant sadism wrecks the RSM’s perfect “system” along with Stevens. On their initial walk up the hill, Williams carefully rephrases his address from “Gentlemen!” to “Ladies and Gentlemen!” In a weaker moment, Harris, the humane Staff-Sargent, calls Stevens aside from a job, advises him to compromise so as to make life easier.

“We had a queer here once, dressed up and did a better show than the real girls….” But Stevens denies being queer. Who really is in The Hill, is a matter of conjecture.

Most of these films, like much of British Cinema, are reflections of a good deal more than passing recognition. Rather they state or imply a point-of-view with regard to the the homosexual, his position as an individual, and his relation to the society in which he lives. Some of this attitude springs from the British sense of honesty and tact which has increased with the recent insistence on sexual freedom. But non-conformity in mid twentieth-century England appears also as a sincere rejection of tradition and rigid ways of judging others. This must be gratefully applauded along with Donal Donnelly in The Knack who answers to “Are you a homosexual?” with “No, but thanks just the same.”

©1966, 2016 by The Tangent Group. All rights reserved.