The Hours

The Hours

Directed by Stephen Daldry

Written by Michael Cunningham and David Hare

Released December 18, 2002

Drama

114 min.

Review by Stephen O. Murray

January 11, 2003.

Complex novels that delve into multiple subjectivities are unpromising sources for the very objective medium of film, though voice-overs conveyed the point of view of the narrators of many noirs (including the dead narrators of Sunset Boulevard and the very color-saturated noirish American Beauty and the black comedy Alfie) and some other retrospective films (Cross Creek and Sophie’s Choice, both adapted from outstanding, much-acclaimed books). Third-person narration often runs amok (The Naked City, Topkapi), though sometimes provides entertainment (Tom Jones, Start the Revolution Without Me).

The San Francisco Chronicle’s excellent film critic, Mick LaSalle, claimed:

Director Stephen Daldry employs the wonderful things cinema can do in order to realize aspects of The Hours that Cunningham could only hint at or approximate on the page. The result is something rare, especially considering how fine the novel is, a film that’s fuller and deeper than the book.

This claim would have gotten my attention even if I had not been surprised by how affecting and brilliant the book was.

That review does not elaborate or substantiate the argument that the film is fuller and deeper. LaSalle wrote: “In a novel, playing with time is difficult without getting fey or abstruse, but in a movie, Daldry can do it with ease.” Although I think the second part of this statement is warranted, the first part—and, therefore, the general contrast—is not.

I recall a Vargas Llosa novel in which two stories were told in alternative sentences (which I found grating, though not fey or abstruse); Faulkner’s Wild Palms (which the late great cinematographer Conrad Hall wanted to film) and Vargas Llosa’s Aunt Julia and the Scriptwriter (and, indeed, much Latin American fiction) tell two or more stories in alternating chapters. Not to mention stream of consciousness writing darting back and forth between memory and some present situation.

David Hare’s screenplay narrows the times shown to three (bracketed with the day in 1941 on which Virginia Woolf put rocks in her coat pockets and drowned herself that is shown before the opening credits and then again at the end). There is a day in 1923 in which Virginia Woolf (played compellingly by an unrecognizable Nicole Kidman) begins writing Mrs. Dalloway, receives an early visit from her sister Vanessa Bell and three children, and tries to escape back to London, having a confrontation on a railroad platform with her despairing, devoted husband Leonard (Stephen Dillane, who won awards in London and New York in the revival of Tom Stoppard’s The Real Thing).

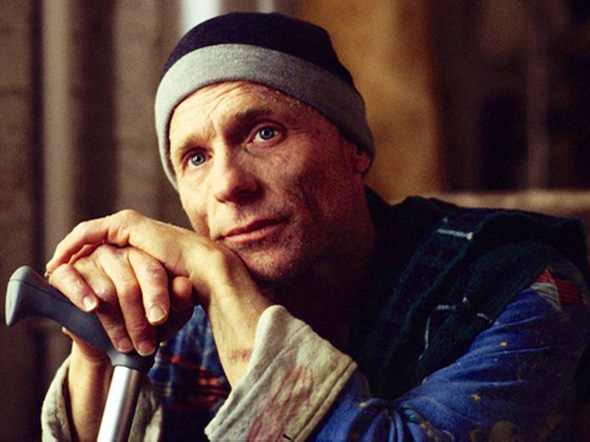

There is a day in 1951 on which a young, pregnant suburban housewife, Laura Brown (played poignantly by Julianne Moore) bakes two cakes for the birthday of her loving husband (a touchingly clueless John C. Reilly) from whom she hides her anguish, is unsettled by a visit from a neighbor who is going into the hospital with possible cancer (Toni Collette bursting out of her dress), and desperately wants to read Mrs. Dalloway. Finally, there is a day in 2001 on which Clarissa is preparing a party in honor of a former lover, Richard (Ed Harris), who has always called her “Mrs. Dalloway” and seems to be suffering from AIDS-related dementia. (Woolf’s heroine is also planning and preparing for a party.) [1]I’d like to know why Laura Brown was reading Mrs. Dalloway. The Bloomsbury industry and the transformation of Woolf into a feminist icon occurred later (in time for Richard and Clarissa’s college … Continue reading

The opening jumps back and forth through the starts of these three days for these three women, and, as the film goes along, there are cuts from bells ringing and flowers arriving in the three stories that are “cinematic” in the Eisenstein manner. The mood of anguish is also bridged from era to era by a very obtrusive Phillip Glass score with a repetitious, mournful piano.

The book obviously does not include a musical score (though one could read it to any number of Glass recordings), and there is an immediacy to each scene in contrast to detail having to be built up in writing. But this gets back to the objectivity of the picture in contrast to the subjectivity possible on the page. The backdrop of the rooms can tell the viewer many things about the lives of the characters, but attention easily can drift to extraneous details. It is “natural” to describe one item at a time, whereas close-ups of particular objects is marked and seems “unnatural,” even when choreographed by a master like Michelangelo Antonioni (as in the end of L’eclisse), let alone by someone without a whole lot of visual imagination like Stephen Daldry.

Besides cutting from narrative to narrative, films allow fluid shots (tracking and panning). However, there is very little of this in Stephen Daldry’s film The Hours. The camera is mostly static, and the film-makers over-rely on close-ups (though I will readily grant that the juxtaposition of close-ups near the end between the septuagenarian-made-up Moore talking and Meryl Streep’s bravura wordless acting in reaction shots is awe-inspiring).

It seems to me that the book is deeper in establishing some of the other characters, particularly Lewis (Jeff Daniels in a puzzlingly implausible turn), Clarissa’s daughter (Claire Danes) and partner (Allison Janney), and in filling in the relationship thirty years earlier of Richard, Clarissa, and Lewis. I wonder if what is said in Clarissa’s apartment during the film makes sense to viewers who have not read the novel? Similarly, I wonder if what is shown of Virginia Woolf with her sister and with her husband adds up for (makes sense to) someone unfamiliar with her situation (especially anyone who fails to register that the drowning was in 1941, not later in 1923).

Hare and Daltrey took to heart the exhortation “Show, don’t tell,” and Kidman and Dillane do very well what they are given to do. But it seems to me that the force of their portrayal rests more on familiarity from outside the movie’s frame with the characters than on what the script calls upon them to do. I don’t think (recall) that everything about the Woolfes is forced into one day in the book. Certainly Mrs. Dalloway was not written in a day, and there is more about (not to mention of!) Mrs. Dalloway in Cunningham’s novel than in the film.

Hare and Daltrey took to heart the exhortation “Show, don’t tell,” and Kidman and Dillane do very well what they are given to do. But it seems to me that the force of their portrayal rests more on familiarity from outside the movie’s frame with the characters than on what the script calls upon them to do. I don’t think (recall) that everything about the Woolfes is forced into one day in the book. Certainly Mrs. Dalloway was not written in a day, and there is more about (not to mention of!) Mrs. Dalloway in Cunningham’s novel than in the film.

Moreover, the echoes of Woolf in Richard are more audible in the book than in the movie. It’s hard for Woolf to start writing, but one of the major themes of the book, the anguish about the gap between what intention and execution in writing (“one always has a better book in one’s mind than one can manage to get on paper” and knowing the odds against immortality are very, very high) is missing. The figures on the screen seem wracked by psychopathology, not casualties of impossible artistic quests. (Yeah, yeah, I know one could argue that Vissi d’arte is in-itself psychopathology, but don’t try to cure me of romanticizing the quest to get it right when one doesn’t even know with any certainty what “it” is!)

What Laura Brown wants is more obscure on screen than on the page. I did not get the impression from the book that she was lesbian, that her problem was wanting to love a woman instead of her husband, son, and unborn daughter. The movie seemed reductionist both for Mrs. Brown and Mrs. Woolf. (Not that there was no incestuous tangle in Woolf’s psychobiography, but both passionate kisses elicited laughter from a San Francisco audience, one which I think is not unfamiliar with representations of same-sex love.)

Partnered to a woman, Clarissa apparently has things “more together, even if she has occasional doubts about the meaningfulness of her well-organized life and successful career (as an editor). I don’t think that the three heroines form three eras have the same clinical depression. Despite her doubts Clarissa has doubt, rather than being a continuation of female depression, the third variation has the male (writer) in the anguished slot, and Clarissa is in the slot occupied by the husbands in the other two variations: caring but unable to supply what the other one wants or to save them from their anguish. (There is also one exception in which one of the depressed characters saves herself and does not feel the regret she is supposed to feel.)

There is much that is impressive in the movie The Hours, including superlative acting in most parts (except Jeff Daniels’s; Ed Harris also seems off to me, still engaged with Jackson Pollock’s demons, and the boy playing his earlier incarnation is only adequate, but the husbands perplexed by their wives’ unhappiness played by the currently ubiquitous John C. Reilly and by Stephen Dillane are fine). Fine actresses (and actors) illustrate the many characters and “events” in the book. Both film and book are more evocative of feelings and eras than narrative. Though it is relatively short, the book is deeper, and I have to reach the familiar verdict that “The book is better,” as much as there is to admire in the movie, including some memorable, intense scenes (the Woolfes on the train platform, Toni Collette’s drop-in with Julianne Moore, Clarissa’s dropping by early to pick up Richard, and Streep listening to Moore) in which outstanding actors more than excel. There’s also memorable performances by water to admire. (And a soundtrack that strikes me as both inferior and less fitting than other Glass soundtracks, e.g., for Mishima and Kundun.)

There is much that is impressive in the movie The Hours, including superlative acting in most parts (except Jeff Daniels’s; Ed Harris also seems off to me, still engaged with Jackson Pollock’s demons, and the boy playing his earlier incarnation is only adequate, but the husbands perplexed by their wives’ unhappiness played by the currently ubiquitous John C. Reilly and by Stephen Dillane are fine). Fine actresses (and actors) illustrate the many characters and “events” in the book. Both film and book are more evocative of feelings and eras than narrative. Though it is relatively short, the book is deeper, and I have to reach the familiar verdict that “The book is better,” as much as there is to admire in the movie, including some memorable, intense scenes (the Woolfes on the train platform, Toni Collette’s drop-in with Julianne Moore, Clarissa’s dropping by early to pick up Richard, and Streep listening to Moore) in which outstanding actors more than excel. There’s also memorable performances by water to admire. (And a soundtrack that strikes me as both inferior and less fitting than other Glass soundtracks, e.g., for Mishima and Kundun.)

I also want to add that updating the party to 2001 doesn’t work very well for anyone familiar with the history of AIDS and HIV-treatment for insured Americans. Richard’s physical plight (and Ed Harris does not look especially sickly) is more plausible in the mid-1990s than in 2001.

Originally published on epinions 11 January 2003

©2003, 2017, Stephen O. Murray