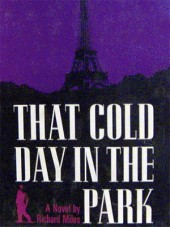

That Cold Day in the Park

That Cold Day in the Park

by Richard Miles

Published by Delacorte Press, New York

Published 1965

Gay fiction: suspense

182 pages

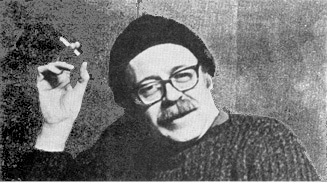

Review by Joseph Hansen (as “J.H.”)

Originally published in the Oct. 1965 issue of Tangents

This is a compelling suspense story.

This is a compelling suspense story.

The plot is not new. Galsworthy used it in The Silver Mask, and it has come before the public as a stage play, a radio play, a television play and, several times, as a film. The story: An older woman befriends a handsome young stranger and is robbed.

But Richard Miles has added a few twists.

Mignon, a handsome blond teenager, had come to Paris where he keeps himself alive by selling his body to homosexuals. He lives with a half-Negro youth named Yves, a handsome animal without ethics or scruples, part time thief, part time gigolo, part time hustler, part time “actor” in lewd nightclub shows. Mignon is in love with Yves … though love is a forbidden word between them.

On a cold day in the park, Mignon is sighted by a sex-starved wealthy woman whose life to this time has been dominated by her mother, now dead. We are never told Madame’s age, but she is probably in her mid-thirties. She leads Mignon home to her luxurious apartment and a curious relationship develops, not really entirely one-sided but certainly entirely hopeless.

The hothouse atmosphere of the apartment is stiflingly erotic. Madame prefers the boy to go about naked. Her efforts to prevent his being bored are typical of the insular intellectual — she reads to him, makes him listen to symphony concerts on the radio, and buys him paints and canvases. Only this expedient really works; he becomes absorbed in painting, she in watching his body as he paints.

It is a tribute to Richard Miles’ talent that he makes this situation sufficiently believable to enable the reader to go on. To make him want to go on, in fact. Madame even nails up the windows to prevent The Blond from escaping. He stays with no definite intention except to enjoy the luxury of his surroundings, the ease of this kind of life. He never encourages her sexual advances, though he knows precisely what she wants.

Madame ultimately does have sexual relations with the boy. But only after a most bizarre murder has taken place, when the boy is terrified of her. Her satisfaction, as she knew it must be, is short lived. Yves comes to Mignon’s rescue. The expected robbery takes place. Sickness strikes — bodily this time, not mental. And, as the poet says, “things fall apart.”

Miles’ writing is curiously stiff, like a bad translation from a foreign language. Maybe this is the result of the young author’s having spent so much of his life in Europe and the Orient. In any case, the language is clear enough, the pace fast enough, the likeness to life sufficient so that despite the weird warp of the story the book makes three hours pass swiftly.

Miles’ writing is curiously stiff, like a bad translation from a foreign language. Maybe this is the result of the young author’s having spent so much of his life in Europe and the Orient. In any case, the language is clear enough, the pace fast enough, the likeness to life sufficient so that despite the weird warp of the story the book makes three hours pass swiftly.