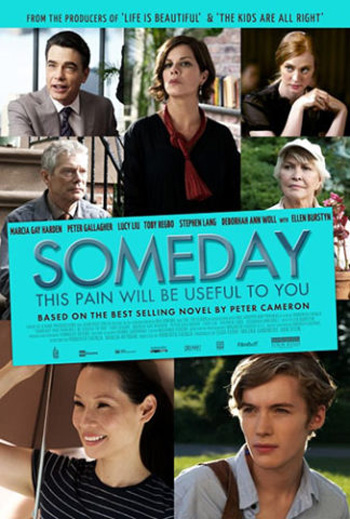

Someday This Pain Will Be Useful to You

Someday This Pain Will Be Useful to You

by Peter Cameron

Published by Farrar, Straus and Giroux

Published September 18, 2007

Fiction (adolescent)

229 pgs. • Find on Amazon.com

Reviewed by Stephen O. Murray

December 24, 2007.

The world of publishing is filled with ironies. A new one is that the 48-year-old novelist Peter Cameron’s fifth novel (and eighth book of fiction) is being marketed as if it were a first novel. Even more ironically, a book in which the narrator is very, very explicit about not wanting to associate with other teenagers is that the premier U.S. literary publisher, Farrar Straus and Giroux, is listing it as for young readers.

Whatever! Someday This Pain Will Be Useful to You’s 18-year-old narrator, James Sveck, is a wonderful creation—though I think way too lucid to be altogether credible an 18-year-old, even one born and raised in Manhattan in affluence. That his parents are divorced is announced in the spiky first sentence:

The day my sister, Gillian, decided to pronounce her name with a hard G was, coincidentally, the same day my mother returned, early and alone, from her honeymoon.

The terser following sentence informs the reader: “Neither of these things surprised me.”

Gillian, about to begin her senior year at Barnard, was “dating” a “language theory” professor named Rainer Maria, and James thought his mother’s marriage ill-advised, not least that she was marrying someone who would honeymoon in Las Vegas.

James has a very refined sensibility, little ability to get along and even less interest in getting along with people his own age. He is supposed to matriculate at Brown University in the fall, after working as a receptionist/gopher at his mother’s art gallery through the summer. He does not think he wants to be ensconced with a bunch of youth. His explanation offers a good sample of James’s style and misanthropic sensibility:

The main problem was I don’t like people in general and people my age in particular, and people my age are the ones who go to college. I would consider doing to college if it were a college of older people. I’m not a sociopath or a freak (although I don’t suppose people who are sociopaths or freaks self-identify as such). I just don’t enjoy being with people. People, at least in my experience, rarely say anything interesting to each other. They always talk about their lives and they don’t have very interesting lives. So I get impatient. For some reason I think you should only say something if it’s interesting or absolutely has to be said.

I like the hedges and parenthetical qualification, the very long sentence with a semicolon (punctuation that most contemporary 18-year-olds do not know how to use) along with a sentence fragment. Plus, the final sentence encapsulates my (upper Midwestern) basis for laconicness.

James also expresses frustrations at “people react[ing] to your being alone as some kind of problem for them,” a problem that they feel obligated to solve. His mother suggests he is passive aggressive and irritatingly “reluctant to show any enthusiasm about anything, or even allow it other people.” (When pressed, he expresses enthusiasm for Rohmer films, Trollope novels, and Denton Welch, a culture universe that does not reassure her and would reassure her even less if she was familiar with the writings of Denton Welch, I think. He also tried to read Proust, but like me at that age, lacked the life experience to understand—or get into, let alone through—Proust.)

And, perhaps even more shocking than thinking about not going to college, he is toying with buying a house in some obscure Midwestern town.

Speaking of “toying with,” in the middle of the novel he toys with his supervisor at the gallery, John Webster, a black guppy (gay urban professional) with a fabricated Internet identity. This game blows up on James.

Part of the humor about his gay Internet identity is that he bristles at each of his parents separately asking him if he is gay (so that they can be supportive). Having a distaste for most human contact, James has had no sexual experience. As he asks, “I could barely talk to other people, so I was supposed to have sex with them?” (I like to answer rhetorical questions and could answer this one, but will show myself capable of occasional restraint!)

John is unusual in not thinking James is gay, and losing one of the few people James thought of as a friend is painful to him. Over the course of the summer, he also loses his maternal Grandmother, whose vintage/retro home in New Jersey is a place of refuge for him. James’s emotionally vulnerable mother did not learn or inherit tact from her mother. (It may have skipped a generation?)

James’s grandmother does not ask him if he is gay, nor does she tell him how he should live his life. He is grateful, and he is not snarky to her, as he is to his father (a successful lawyer), mother, and sister—not to mention to his agemates on a disastrous conglomeration of the best and brightest of America’s youth outside the nation’s capital, a loony organization calling itself “The American Classroom, “ an expedition so disastrous that James’s mother insisted he undertake psychotherapy. (He is an upper-class native New Yorker so should have a therapist, no?).

In therapy sessions, Dr. Adler attempts to get James to talk about how he had felt on 9/11. His high school (Stuyvesant) was close to the World Trade Center, and he saw it leveled. (This emerges late in the book and makes the quest for a low-rise home in a small Midwestern city seem more understandable, though what he would do there remains a big question for me.)

Not without reason, James feels that (other than John and his grandmother) people rarely notice him—never mind understand who he is, or what he feels or wants. Between the broken home and the collapsed skyscrapers, a lack of sense of security is comprehensible, though James never seeks pity from anyone, including his readers.

James hopes that once he is an adult, things will be better, though he starts to suspect that “the adult world was an nonsensically brutal and socially perilous” as adolescence. Moreover, Rainer Maria (a college professor), in expressing approval for not going to college, pushes aside Gillian’s objection by telling her (in James’s presence), “If everyone had to believe in the work he did, not much would get done in the world.” (I won’t get into the “art” on display in the gallery where James and John work for James’s mother(’s aspirations to be a culture gatekeeper).)

James and his milieu are superb creations. The book may appeal to some alienated adolescents, but it provides great enjoyment for those who prize limpid prose and irony. Someday This Pain Will Be Useful to You is a novel of sensibility and of character without much plot. It does not have the profusion of characters of my favorite Cameron novel, Leap Year, but that was originally a serial requiring that a lot happen.

BTW, I am as dubious as James is about the sententious title claim. It’s the kind of remark that reasonably instills distrust in those to whom it is dished out.

And, although I didn’t find a place to force into my review, I have to quote another Jamesism:

My mother was right, but that didn’t change the way I felt about things. People always think that if they can prove they’re right, you’ll change your mind.

Peter Cameron’s Previous Books of Fiction

Short story collections:

- One Way or Another (1986)

- The Half You Don’t Know (1997)

- Far-Flung (1999)

Novels:

- Leap Year (1988)

- The Weekend (1995)

- Andorra 1997)

- The City of Your Final Destination (2005)

Cameron has a website (that I have not explored beyond getting the publication dates for the list just above.)

Published by epinions 24 December 2007

©2007, 2016, Stephen O. Murray