Snow Fall

Snow Fall

by Joseph Hansen

(as “James Colton”)

Part 2 of 3

Originally published in Tangents 1.4

January 1966 • Pages 9–13

Continued from Part 1 • Proceed to Part 3

Frank Hubbard told his story.

At the Wisconsin college where he had taught before transferring to Bryant, he had met an exceptional student named David Warsaw. The boy was intent upon writing, absorbed and talented. With surprising suddenness one evening he had turned to Frank Hubbard for love, physical love.

It was to Hubbard a fulfillment beyond his powers to have imagined. He was married, but the marriage was conventional and the girl herself extremely so. A nice girl, happy with him. But David Warsaw was like some other kind of being. Special. Set apart. And he and Frank Hubbard were very happy.

“Then this chance came, right after my doctorate—my book. David would have transferred too, wanted to. But there was this chance for him to work with two important poets there this summer. He’d been talking of nothing else. I made him stay… You should see him. No beauty. Wait.”

Hubbard dug into his wallet, took out a dog-eared photograph, and flipped it across the desk to Creighton. It pictured a tall, gangly lad standing to his ankles in snow, hands thrust into the pockets of a mackinaw. He was squinting against the white daylight but even in the small photograph Creighton saw, or thought he saw extraordinary sensitivity in the boy’s face. He gently handed back the photo. “I see. And—?”

“Like a colt, high strung, all taut wires, all nerves.” Hubbard bent his head and busied his hands pushing the picture back into his wallet. His voice was muffled. “This summer all the wires broke.” He looked up, eyes swimming in tears. “They were very thin wires, and when the slightest thing…the slightest wind passed, they hummed. You had to be gentle with him. Very gentle.” Hubbard rose quickly and stepped into the shadows, stood staring at the nearly invisible backs of books along the shelves. “I don’t know what somebody said or did or maybe he read a great stupidity in a newspaper…or maybe he saw some great horror (God knows the world is full of them)…I don’t know. But all the wires broke.”

“He’s…in an institution?” Creighton asked softly.

“Raving,” Hubbard said. “Completely gone. Utterly disoriented—that’s the word, isn’t it? Disoriented. Out of it, as the kids say.”

“There are remarkable new drugs.”

Hubbard grimaced, dropping again into the leather armchair. “There are, but the doctors aren’t hopeful.” He felt for another cigarette, then pulled the pack from his shirt pocket and crumpled it. Empty.

“Do they really understand enough about these things to write the boy off?” Creighton opened a desk drawer and found a dusty package of cigarettes. “They’ve been here a while,” he apologized, “but perhaps the cellophane has kept them fresh. They haven’t been opened.”

“Thanks,” Hubbard said. “No, maybe they don’t. But it’s too remarkable a brain to cut into or shock. His people won’t allow it. So the best prognosis they’ll offer is that little by little his lucid periods may lengthen. Maybe. After while.” He tore off the cellophane, opened the package top, talking. “It hit me very hard. Twenty-sixth of July. A bright Monday, 8:30 in the morning. His mother wrote. Good woman. It hit me too hard to hide it. Betty wanted to know what was wrong. Hell, the man you’re married to sits down and cries, you want to know. And I told her. I had to tell somebody.”

“And that was that?”

“She left. Went back to Wisconsin.” He lit the cigarette. “Divorce is under way. I keep getting papers from lawyers.”

“I’m sorry,” Creighton said.”

“So,” Hubbard smiled wanly, “it was a lousy summer.”

“It was, indeed,” Roy Creighton said. “But, perhaps, now, the worst of it is over.”

“Yes…you had your troubles too,” Hubbard said. “I have an artfully rebuilt right cheekbone and an artfully matched glass eye. My ribs once more work as required. But I brought on my troubles out of sheer folly. I alone am responsible.”

“How responsible is anyone when, as the books say, flesh calls to flesh?”

“You don’t blame yourself for this boy’s condition?”

“Not in my lucid periods,” Hubbard said grimly. “But things get to you at night, alone, in the dark.”

“I know,” Roy Creighton said.

…

Virgil Apperson, balancing his weight like a hippo on a tightwire, crossed the faculty dining room. With hands jeweled as a late Roman emperor’s he set down his tray of luncheon, drew out a chair, and seated himself opposite Roy Creighton. Creighton cursed inwardly. He ought to have gone home for lunch but, mentally involved with a student’s question after his morning lecture on poetic method, he had forgotten that Frank Hubbard had gone up to the city to see his lawyer today.

“You’re all alone,” Apperson smirked. Like a priest performing a rite, he lifted one dish after another from his tray and arranged them in an occult pattern on the table before him. “That’s seldom the case these days.”

“I guess it is,” Creighton said.”

“You and young Hubbard seem to have struck up quite a friendship.”

Creighton took a mouthful of food and grunted.

Apperson studied him ironically, a dainty wedge of chicken croquette balanced on his fork. “Hubbard must have a gift. You’ve always been a solitary, n’est-ce pas?” He popped the bite into his rosebud mouth. “Certainly you and I have never been able to get close—for all we have in common.”

“Hubbard’s writing a book on the decline of regionalism in the American novel,” Creighton said stiffly. “I’ve done some work on the Northwest men, H. L. Davis, Ernest Haycox. Hubbard asked for my help.”

“All work,” Apperson twinkled, fat face rosy, “and no play?” His eyebrows made the query arch. “It seems to me I saw you together last Saturday evening at the Budapest Quartette recital, didn’t I? And Evalina Finch tells me you were at the opening of the new show at the municipal art gallery in the city the weekend before—together. I know you two never miss a football game.”

“I’m sure you don’t,” Creighton said caustically. Apperson’s young man this year was the Bryant team’s left tackle, a gigantic, square, blond youth named Halverson. “How did Halverson like the Budapest?”

“He finds Beethoven conducive to sleep,” Apperson sighed. “Mercifully he doesn’t snore.” Apperson blinked his eyes rapidly. “Does Hubbard snore?”

“You know…” Creighton glanced around the big, drab dining room, “I see a lot of vacant tables. Wouldn’t one of those have suited you as well as mine?”

Apperson’s rosiness faded. “Well,”he said, “really! Your air of moral superiority would he laughable if it weren’t so rude. What right do you suppose you have to sneer at me? After what you did this summer?You’d better come off it. We’re not as unlike as you think. If I were you, I’d cherish the friendship of a man in my profession, on my own campus, who shared my predilection, who understood.” Then the anger vanished, replaced by taunting wit again.” Besides, I was Dan Cupid for you and Hubbard—somewhat oversized for Cupid, but none the less, my arrow went straight. Isn’t that so?”

“I apologize,” Creighton said softly, hopelessly.

“I’m florid,” Apperson admitted, actually reaching out and squeezing Creighton’s hand—who looked around, the blood rushing to his face, afraid somebody might be watching: no one was. “I’m florid, but I do have a good heart.”

Creighton made an effort to smile. “Sorry,” he said. He nodded at his plate. “I’m afraid I’ve finished. Some work to do in the library. Will you excuse me?”

Apperson nodded wryly. “Of course. Who am I to keep you sitting idle?”

Crossing the campus in a dismal rain, Creighton’s mouth twitched. Does Hubbard snore? Apperson’s impudence rankled, but not so deeply as his own unspoken answer: I don’t know. Apperson was mistaken—he and Roy Creighton were not alike. Apperson was not afraid. The campus, the whole academic world, the world of books and critics too, knew he was homosexual. And he didn’t care—or made a good show of not caring. But Roy Creighton was afraid. Apperson was happy, or least fulfilled. How, with that gross, quivering body of his, he managed to lure into his bed the strong and stupid youths he favored, Creighton couldn’t imagine—nor what they did once there. His own body was spare, largely unchanged from his teen years. Naked he wouldn’t strike the absurd figure that Apperson would, or most men crowding fifty. Yet he was afraid.

…

He came under the shelter of the library portico. The drizzle was a cold one and he shivered in his macintosh, but he had no wish to go inside. He stood watching the slow drip from the blackened tree branches onto the brown, soggy lawns and leaf-clotted paths. Some small birds, unseen, rustled in the dry shrubs at his feet, sheltering. Friday afternoon. The campus was nearly empty, students almost all on their way to Pierce College in the next state for tomorrow’s football game. Only an occasional gray figure moved along the paths, shoulders hunched, mournful.

But his fear was a habit, 30 years ingrained. There had been excuses for it, justifications—one justification paramount—he had not wanted to hurt his mother. Mother. With what sharpness, suspiciousness, she had questioned his occasional very tentative associations with certain students in whose faces he read unmistakably a likeness in their emotional needs to himself at their age. With these he had reasoned there could be no force to the scruple about “corrupting youth.”

Yet in the end he had lacked the courage to make sexual overtures. Why? Complications. Endless. Where, for example, could such episodes take place? Where, that would be safe? He grimaced at himself now, gazing sightless across the campus veiled in gray rain. Even if the way had been smooth and simple, he wouldn’t have dared. Too much at stake. Young people were unstable. A careless word to the wrong auditor and Roy Creighton’s world would have crumbled around him in ruin and disgrace.

But Mother was gone now. He had tenure plus a reputation in the wider world that made his presence an asset to Bryant they would not relinquish if there were a way around it. And Frank Hubbard was no nervous child. And…he loved Frank Hubbard. The word came reluctantly to his mind and made him shift his feet uncomfortably, shrug, become aware again of the cold, and shiver. He found it romantic and absurd, that word. He a man of 47, Frank a man of 35—two grown men. Neither young, neither in any way beautiful—ah, except that Frank was beautiful, wasn’t he? His glowing eyes, his dark skin, his taut, small, compact body, his quickness, keenness, laughter. Whatever anyone else might think, to Roy Creighton he was beautiful. Chemistry. Somehow—and he had bleakly feared himself no longer capable of such an emotion—somehow, he was in love with Frank Hubbard. And how did Frank feel?

That, of course, was the crux of the matter. Certainly Frank had come to him in the first place. It was Frank who had arranged all their subsequent meetings. There was every reason to take courage from this. But could he find it? Wasn’t his cowardice a habit too entrenched to overcome? No. He must try. Being with Frank…oh, in the warm car with the music on the radio, driving to the art exhibit for example, and in that pleasantly paneled restaurant by, of all romantic things, candlelight, he sometimes wanted, so desperately it brought tears to his eyes, to reach out, to touch the younger man, to kiss his mouth…

Roy Creighton’s face burned in self derision. But that was wrong. This was an honest emotion. He must not smother it in sophistication, must not, as the young people said, play it cool. This might be the last possibility for happiness his life would offer. He would never forgive himself if—even at the risk of being turned away: it had been, after all, a boy Frank had loved, no gray-haired man—if he did not try. He would try. Tonight.

…

Mrs. Bendo, square and ruddy, hair dyed flaming in vain mockery of its vanished girlhood glow, opened her honest blue eyes at him. “Why, Professor, what’s wrong? You’ve hardly eaten a bite. Mary Lou? Anything wrong with the fritters?”

Roy Creighton laughed apologetically. “They’re wonderful. I’m sorry to be dilatory.” He forced himself to act hungry. He was not. He was absurdly nervous. His stomach was full of butterflies. He could think only of Frank Hubbard and how he must, tonight, tonight, speak to him, make his bid. Under Mrs. Bendo’s doubting stare, he repeated, “They’re delicious,” and crammed his mouth.

“You act like you’re having trouble swallowing. Face painful again? You should have given yourself time for another highball before dinner.”

“My face is fine,” he said.”

“Well, I know the rain’ll play hob with an old wound. Mr. Bendo’s bad knee always—”

“Oh, Mother,” Mary Lou said, “the Professor doesn’t want to hear about Daddy’s knee again.” Then she turned her head. “What in the world is that?”

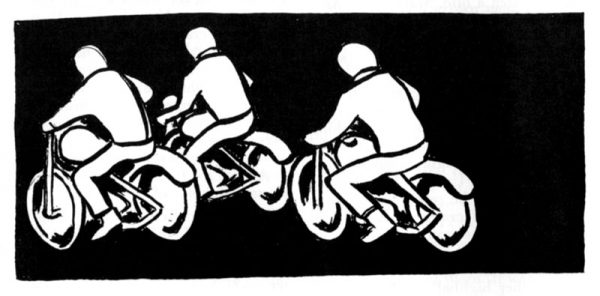

Thunder, Roy Creighton thought. But no. Rain—a sudden downpour? Not that, either. This mutter was mechanical, a low, steady, deep-throated thrum. Engines. Aircraft? Mary Lou pushed back her chair from the table and went to the dining room window, pushed aside the curtains, cupped her hands around her face against the glass. The noise grew, heating the hushed evening air in pulses like a great, angry heart.

The girl said, “I can’t see… Oh, look!”

Roy Creighton rose to stand beside her. He saw nothing but his own reflection and the girl’s in the dark glass. He went to the light switch on the wall beside the kitchen door and pushed it, darkening the room. Mrs. Bendo made a sound and stood up too and joined them. Outside, night had not quite closed in. It was still possible to seek darkly what passed along the street with its ominous rumble. Motorcycles. Heavy, brutish, a crawling double file. How many? Ten? Twenty? No headlights. Only the great throbbing sound.

Roy Creighton felt as if something had struck him a terrible blow in the chest. Dimly he was conscious of Mrs. Bendo’s voice: “What are they—policemen?”

And Mary Lou’s: “No, it’s one of those awful clubs.”

“You mean like they wrote up in the paper? Them that wrecked that little town up in Connecticut or where ever it was? Why, Professor, what’s wrong? You are sick.” Her strong hand gripped his arm as he started to fall. “Here, Mary Lou, take hold.”

But he caught and steadied himself, though his voice wobbled. “I’m all right. Thank you. Just giddy for a moment, there.” They were going away—on up the block, on through the campus following the curving drive, on out through the sparsely settled town fringes with their chicken farms and dairies, on across the red steel bridge spanning the river, onto some other place. They were going away. He gave a laugh and stepped again to the light switch.

But they came back.

It was nearing eight. Frank Hubbard should arrive shortly. He bent to the cabinet where he kept the whisky, opened the door, lifted out the bottle. Nearly empty. He peered at the seltzer siphon. Adequate. Straightening, he started for the door to the hall to summon Mary Lou —and he heard the rumble again. Ah, but they’d simply he going past once more.

Wouldn’t they?

“Mary Lou? Another bottle of White Horse, please?”

Her voice from the hack of the house. “Coming.”

They would go past. Surely he was mistaken. He was indulging fantasies. His experience had made him too associatively vulnerable. Motorcycles. Why there were hundreds of thousands of motorcycles in this country. Mary Lou came running lightly, smiling, with the bottle. He took it with thanks and turned back into the study, aware of Mary Lou going on along the hall to the oval of glass in the front door, and peering out.”

Why, Professor,” her voice came, muffled, “they’ve stopped, some of them. And the rest are going around and around in the middle of the street.”He stood arrested in the act of setting the bottle down on the desk. Cold sweat trickled down his ribs. Like a panicked child, his mind shrieked. No! No no, no no! But there came the clump of boots on the porch. There was the doorbell.

“No!” he heard himself shout aloud.

But the door was already open.

Doomed, he walked into the hall.

Covent Blessed stood there, grinning.

to be continued …

A Tangents Exclusive

A Tangents Exclusive

This page was sponsored by Robert R. Cook and C. Todd White in honor of the 80th birthday of their friend, Joseph Hansen, on July 19, 2003.

©1966, 2003, 2016, by The Tangent Group. All rights reserved.