Snow Fall

Snow Fall

by Joseph Hansen

(as “James Colton”)

Part 1 of 3

Originally published in Tangents 1.3

December 1965

Roy Creighton raked the yard. All along the street great maples had scattered their red and golden leaves across dying lawns. At the end of the block the ancient elms of Bryant College had blanketed the campus with brown. The smoke of bonfires was pungent in the evening air.

Creighton paused and leaned on the rake, a little weary, breathing the tang of the burning leaves and smiling to himself. This was the time of year he loved best—summer spent, with its rank greens, its humid heat, its raspy insect hum—the return of crispness to the air, and with it the excitement of the beginning of a new term.

But no autumn of his life had moved him as did this one. He had so nearly failed to reach it. Sudden tears blurred his eyes. He brushed at them indignantly with the ragged cotton gloves he wore for gardening. The horror that had overtaken him last June in the dim, hot room of a cheap walkup hotel on a dingy back street of that city where he had gone in search of—what, forgetfulness, love?— an insane search with a nightmare ending—apparently had not only half blinded him and nearly wrecked his health forever, but had turned him sentimental as well.

What a picture he must make for that clutch of students passing now, arguing, laughing, kicking the leaves—Roy Creighton, Ph.D., clinging wanly to the handle of his rake and weeping in the twilight! With a grimace he bent, scooped up the last heap of leaves into the bushel basket, picked up the basket and carried it to the back yard where a great heap of leaves already smoldered.

He retrieved the rake, poked the heap into flame, overturned onto it the new basketful of leaves, and poked it again. When it blazed, he hung the rake on its rusty spike in the cobwebby woodshed, dropped the gloves into the basket and hung that up, then fastened the shed door. He started toward the house—the kitchen window bright where Mrs. Bendo washed the supper dishes—but the play of small flames on the bonfire arrested him. He stopped and for a long time stood gazing into them. When he slept, his mind was haunted by the hurt that had been done him. Again and again he cowered in the corner of that grubby hotel room, the red neon sign across the street spraying it with spasms of light like blood from an opened artery, and again he felt the heavy boots crash against his ribs, again and again woke screaming with the sound of their splintering in his ears.

But his waking mind was haunted by a deeper fear, fear of the insane someone who lived inside him and might at any moment take him in charge once more and drag him to his doom. After all, when the thing had happened, he was 47 years old. There had been not one such episode in all his life before—not since he was 17 and had known Bovy Welles, known him to the bare skin, bewildered and afraid but unable to resist going back to Bovy again and again, and luring Bovy again and again to himself, Bovy laughing and embarrassed and unkind except when lust stripped all his fundamentalist conventionality away along with his clothes … Bovy who suddenly married and went inaccessible and left timid Roy Creighton to his own bleak, solitary devices …

In time he smothered his wants in work, in learning, in academic achievement, his loneliness by clinging close to his mother. Mother … It had been her death, of course, that had set him off. He’d known it was coming, thought himself prepared for it, and perhaps he was. What he had not been prepared for was himself, how he would feel when she was gone. His tenure had come at the same time as her death. He had been free, really free for the first time in his life. And how had he coped with that freedom? In the most bizarre and unexpected way.

Armed with 1,100 dollars in cash—the bank had suggested traveler’s checks; he had merely smiled and shaken his head—he had driven to the nearest large city, to that blowzy street, that flyblown hotel, to sleep during the suffocating days, to prowl all night—barrooms, neon-crazy, shrieking with steel guitars; public men’s rooms reeking of disinfectant and stale urine, with their strange, speechless ceremonials of lust; midnight parks with their furtive shadowy denizens, young pale faces with the eyes of rabbits, the armed faces of the middle aged, the wolf faces of the old.

The frail little lad called Chick, in his pitifully spindly dungarees and pointed shoes, blouse like a girl’s, plucked eyebrows, paint on his sunken cheeks, always by the fountain rim; the lanky, freckled, easily smiling Oklahoman in cowboy rig; the blond, ruddy cheeked high-school type with a guitar he never played; the sullen Negro youth with the body of a Watusi prince, slouched lazily against a tree trunk; and beautiful Covent Blessed, arrogant and aloof, astride his glittering Harley, sometimes with others of his kind, sometimes alone…

Creighton had gone among them fascinated, beside himself with lust, not himself at all, in fact, insane, rushing upon his own destruction. One by one he had taken them up to that room and had lived out there, upon that butt-sprung bed, fantasies suppressed so deeply all those years he could not recognize them when they came to life. Night by night, hustler by hustler, stud by stud, trick by trick—adrift in an alien world, he expected an alien tongue—he had them all, until he got to Covent Blessed. Or rather, until Blessed got to him.

“Do you really dig that dirt?” He slid onto the stool next to Creighton. It was three in the morning. The glaring all-night coffee bar near the park was empty except for the two of them and the pimply boy in smeared apron yawning hack of the counter. Blessed smelled of leather and of great cleanliness. “You could do better. You’re a good-looking John.”

“Thank you.” Creighton nudged his cigarettes toward Blessed. “Perhaps I could.”

“They’re none of ’em more than five-buck hustlers.” Blessed dumped sugar into the steaming brew the tired boy brought him. He stirred it, sloshed in cream, lit one of Creighton’s cigarettes. “Chick don’t get that half the time. So hot for it he gives it away. Cock’s his hangup, like some eats get hooked on pills.”

“Yes, and he’s half starved,” Creighton said.

“Lunch is all he wants,” Blessed grunted. He drank from his cup, little finger extended. A tough lady. “He told me you gave him twenty bucks.”

Creighton made a noncommittal noise. He had—and to all the others too, and each time with mumbled apologies that it wasn’t more.

“You want to make it with me?”

Startled, Creighton looked at him and saw that the color of his eyes was almost violet. It was, of course, precisely what he wanted. Night after night he had studied this Bellerophon straddling his motorized Pegasus—hair a tumble of basalt curls, face of Zeus, skin white—no riding in the burning wind for Covent Blessed. Did he ever ride or merely sit? The body, inside the tight pants and T-shirt, that of a late, slightly gynandromorphic Apollo—marble.

“Yes, I Want to—very much.” Creighton’s heart gave great laboring thuds and his hand shook so that his cup rattled like an alarm bell in the saucer and the counter boy came like Lazarus with the coffee urn.

“Okay, only I’m expensive.”

“How expensive?” Creighton waved the counter boy away.

“If they’re worth twenty…” Blessed rose, boots creaking, “I’m worth ten times that. Right?”

“Doubtless, but I haven’t that kind of money.” With a twinge of guilt—remembering this was his mother’s life insurance he was squandering—but only a twinge, and only for a moment, he offered, “Say twice twenty?”

“Make it fifty and you’re on,” Blessed said.

“No forty, but—” And here he made his mistake. “Again tomorrow night, same price.”

Blessed stood very still. “And the night after?”

“Yes, yes,” blurted reckless Roy. “However many more nights you wish.”

“Cash? You got it on you?”

Creighton smiled wryly. “Did you expect me to offer you my personal check? I have cash in my room.”

Blessed turned toward the door. “Let’s go …”

It was the corner of the dresser drawer that had cost him his right eye, the drawer he had opened to take from his hoard two 20 dollar bills for Blessed, who sat in the dim red dark on the edge of the broken bed, tight Levis on again, thrusting his feet into his boots. Creighton had no time to shut the drawer. He was flung aside, flung hard against the bed’s iron foot, and Blessed was clawing out the money, all that remained —what, 600, 700 dollars?

“No, now wait, be fair,” Creighton cried, and stepped toward him.

It was then, with a grunt, that Blessed yanked the drawer free and swung it, slashing, into Creighton’s face, the cheekbone crumpling, the eye springing from its socket to hang by bloody strings …

…

“Professor?” Mary Lou Bendo came toward him now across the dark yard, a mousy girl of fifteen with taffy-colored hair, the housekeeper’s daughter. “There’s a Dr. Hubbard on the phone. Wants to talk to you. Brrr!” She hugged her frail self. “Aren’t you cold out here?”

“No, the fire—” he began, then saw that the fire had died and that all around him was darkness. He shivered in his old cardigan, and followed the girl into the house…

“Hubbard here. Dr. Creighton. Remember me? We met last spring at Dean Brubaker’s, but I haven’t seen you so far this term.”

“I’m on a light schedule,” Creighton said. “I’ve not been well. But of course I remember you, Hubbard. How are you?” Creighton sat down at his desk in the book-lined study. The furnace had been cleaned during the summer. Its smell was metallic with this, its first use since. But he was grateful for the warmth, the lamplight, the fine old sameness of the place. All it lacked was his mother to look in now and then and inquire if there was anything he needed.

He asked Hubbard, “How’s that book of yours coming?”

“That’s why I’m calling,” Hubbard said. “I’ve finished the chapter on the Northwest novelists and I’d like you to look it over. That’s your corner of the country.”

“I like to think so,” Creighton smiled. “I’ll be delighted. Why not bring it by right now? I’m free.”

“Thanks. That’s generous. I’ll be right there.”

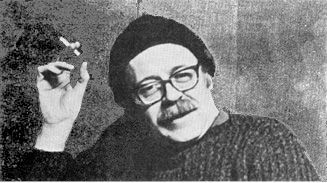

Creighton remembered Hubbard as small, dark, vital, perhaps 35. The man for whom he opened the door 10 minutes later had changed. His boyish shock of black hair was streaked with gray. Was it pain or grief that dulled the dark eyes once alive with laughter? Creighton remembered the compact muscularity of his body in its thin white shirt when he’d removed his jacket in the heat of the afternoon at the Dean’s garden party. The suit now hung on him loosely. He was thin. He’d had a fine, brown gipsy color last spring. Now he was sallow. The hand that accepted the whisky and soda Creighton served, trembled.

“I was sorry to hear about your—accident,” Hubbard said.

Creighton sat down and smiled ruefully. “It’s all over now, but I spent the summer in the hospital.”

“Mugging, robbery, that sort of thing, wasn’t it?”

“The wicked city is no place for a provincial pedagog.” Creighton reached out for the manuscript that lay on Hubbard’s knees. When the younger man handed it to him, Creighton was unable not to make his own over-personal inquiry.

“You don’t look at all well, yourself.”

“I’ve been working pretty hard,” Hubbard said. “Book’s damn near done.”

“Don’t let them pressure you too much on this publication thing,” Creighton advised. “It’s been attacked too often in the press lately. The accent will be on teaching in the future, I expect.”

Hubbard lit a cigarette. “It’s my own pressure, not Bryant College’s.” He suddenly looked straight at Creighton and his voice was harsh. “It’s been a rotten summer for me. The only way I knew to shake what happened was to work.”

“It’s a good way.” Creighton with a wry smile glanced aside at the shelf of his own books, a dozen of them, that represented his own flight from disappointment and frustration. “What happened—or would you rather I didn’t ask?”

“No, I wouldn’t rather you didn’t ask.” Hubbard’s wide mouth broke into a harsh grin that showed strong, straight teeth. “I’d rather you did. Doctor. In fact…” He stood abruptly and picked up the sheaf of papers he’d brought. He held them by the corner and shook them. “I’ll be honest with you. This thing was completed weeks ago. I didn’t come to talk about it. I came because—” He broke off, sat down again, drank deeply from his glass. The look he gave Creighton was that of a begging dog.

Creighton was oddly moved and disturbed. He blinked in the lamplight. “Because?”

“No—the paper does need your reading,” Hubbard said lamely. He tossed it onto the desk again. “That’s … that’s all. Don’t pay too much attention to me. I’m upset, as I said. It’s been a mean summer.” He ground out his cigarette, tipped the glass and drained it. Setting it down, he rose once more. “I’d better clear out and let you read.”

“Let me understand,” Creighton said. “You want someone to talk to. That’s really why you came?”

“Yes, but I feel cheap. You see, I’d never have come only today I ran into Apperson—you know, Germanic languages.”

“Yes, I know Apperson.” Creighton experienced an inward chill. Apperson had come to the hospital to visit him this summer, all the way to the city simply to gloat. A notorious homosexual, he had been in trouble with the college several times during his 28 years on the faculty. His victims, students, a basketball coach, had been dismissed. Somehow he had survived, fat, disgusting, but always companioned. Creighton avoided him. But this summer he had come mincing, smirking, into that white hospital room, to sit beside Creighton’s bed, ostensibly as comforter but really as tormentor, reconstructing with lip-licking avidity and astonishing accuracy the circumstances that had brought his ailing colleague to disaster.

“Apperson has a very loose mouth.”

“That’s why I feel cheap,” Hubbard said. “I agree with you. He’s loathsome. But he told me—”

“I can imagine what he told you,” Creighton said. “Did you believe him?”

“I—” Hubbard shifted uneasily. “Would it make sense if I said I … wanted to believe him.”

“Why?” Creighton squinted, baffled. “Why should you? And why should you then come here? No.” He stiffened and his voice went cold. “I’m afraid I don’t understand.”

“Oh, Lord.” Hubbard rose and picked up his manuscript from the desk. “I’m sorry. There’s no excuse. Ah, the hell with it!” He turned away. But with his hand on the doorknob he swung back, agony in his eyes. “Look, please let me explain. It’ll only take a few minutes. I’ve got to. If I can’t tell you, I’m washed up anyway. You’re my only hope. Melodrama, huh?” He tried for a smile and missed.

Creighton watched him, mystified. “If you want to tell me something, Hubbard, of course do so. I simply cannot understand what Apperson and his vile imaginings have to do—”

“Look, Dr. Creighton, I’m gay.” Hubbard came back to the desk and leaned over it. “Do you know what that expression means?”

Creighton stared into the tormented face, unable to trust himself to answer, shocked beyond measure, yet with a strange feeling of joy leaping up in him. It made him laugh. Hubbard winced. “No, no, excuse me.” Creighton reached out to him. “I’m laughing at myself, not you. Yes, yes, I know the meaning of the word gay. And now I see what you meant, why you’re here. When Apperson told you about my misadventures in the city—”

“I jumped at the idea there was somebody at Bryant I could talk to,” Hubbard finished. “Of course, I knew Apperson’s gossip couldn’t be trusted. I came meaning to feel you out on the subject somehow. Instead I got clumsy and wrecked everything. I’m sorry…”

“No.” Creighton stood. “There’s nothing to be sorry for. While vicious and inaccurate, Apperson’s tale has its element of truth. He’s perceptive.” Hubbard sighed relief. “That’s what made me believe him to the extent I did. He knew about me. First day I walked on campus. He knew, and he knew I knew he knew. He’s uncanny.”

“Yes,” Creighton smiled, “I’m afraid the fact of your very pretty wife easily deceived me.” He saw pain flicker in Hubbard’s eyes again and picked up the empty glass from the desk corner. “Sit down,” he nodded. “I’ll just fix us another drink and we can talk.”

to be continued…

A Tangents Exclusive

A Tangents Exclusive

This page was sponsored by Robert R. Cook and C. Todd White in honor of the 80th birthday of their friend, Joseph Hansen, on July 19, 2003.

©1965, 2003, 2015, by The Tangent Group.