The Pressing Need for Law Reform

The Pressing Need for Law Reform

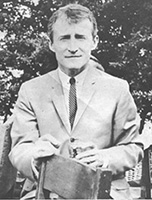

by Don Slater

Tangents • Vol. 1 No. 5

February 1966

Two recent happenings in the city of Downey, California, involving persons suspected of being homosexual point again to the fact that if the function of the law is to protect the community and the individual from harm, then it is all too clear that the present laws in California, and the laws in most of our other states, on homosexuality are failing, for these laws are themselves a cause of harm.

There is probably nothing that puts a stronger weapon in the hands of the blackmailer or unscrupulous law officer than our present penal codes. The new policy statement dealing with sexual behavior issued by the Southern California American Civil Liberties Union, while it adds to the growing support for legal changes, also serves to remind us that despite the mounting evidence of injustice and capriciousness, arguments in favor of law reform seem to get no place and end up as just so much debate.

Legislators in both England and the United States do not have the courage of their convictions when the subject is the regulation of sex acts generally termed “contrary to nature.” Either this is so, or they don’t trust the collective conscience which has for some time been of the opinion that the present laws are bad. Can laws be tolerated or exist that make those adults who voluntarily indulge in sexual acts that deviate from the “norm” the largest criminal class in our communities? It is, of course, absurd. Can we, should we, try to distinguish between legal and criminal love-play in the bed? To attempt to do so is a monstrous and chaotic trespass on the affairs of human beings.

We often hear discussions on the subject of law reform nowadays, and we seldom hear a dissenting voice. People perfectly understand that there will always be some individuals who will be indignant over “unnatural” sex acts (whatever the term may mean), but what the majority no longer understand is why this moral indignation should be transferred to criminal law. Is it too much to expect legislators to understand and act upon this knowledge?

There is a certain logic in the argument that the law cannot be too remote from what most citizens believe is right. And on the matter of the right of the individual to be free from legal prejudice based on his private sexual behavior public opinion is changing; and it is changing in the right direction. But even if it were not, legislators should seriously consider and support the reforms in the morals sections of the penal codes now before committees in many states including California. If legislators are not able and not willing to be a little more rational, a little more knowledgeable, even a little more humane than the majority of people, what is their justification for existence? No doubt one day legislators will look back and wonder why in the name of common sense and common justice they did not pass these measures before.

The two cases in Downey, California, show the mistake of continuing our laws as they now stand. In the first instance, a man whom we will call Mr. Smith went to the Downey police after some of his possessions had been stolen by a hustler he had picked up. The situation was a little sticky, and most homosexuals under our present laws would not have gone to the police. However, this man did, with the consequence that when the police learned the nature of the case they actually threatened to prosecute him—not the hustler.

One detective, Matt Skobell, showed the utter futility of Mr. Smith’s ever having sought such recourse. Skobell voiced the opinion that since the two men had slept together, then the stolen goods should he considered as community property like that belonging to a man and wife, and that the hustler had a perfect right under the circumstances to take what he wanted. Downey Detective Snyder also relieved his prejudices on the matter by adding that he was “not interested in being a referee for homos,” and that if Mr. Smith did not stop bothering him and the accused, he would make life extremely miserable for him.

This is undoubtedly not an idle threat. Present laws on homosexuality indirectly offer Detective Snyder an opportunity to impose his disgust, which is a personal and private emotion, into what should be a routine investigation into an alleged theft. At the same time the law protects a hustler, and would-he blackmailer, who was certain that his victim would never go to the police.

The other incident illustrates a similar injustice and is equally representative. It concerns a schoolteacher [Don Odorizzi] who was arrested on a homosexual charge by the Downey police.

Before the teacher had even been before a judge on the matter, the Downey police went to the school where he worked and told the school secretary (not the principal) what had happened. The police also tape recorded a conversation lasting several hours about the teacher’s sex life and sex experiences generally—having nothing to do with the circumstances of his arrest—before they released him on bail. The school authorities immediately forced the teacher’s resignation, and later initiated proceedings to revoke his state teaching credentials. The majority of these liberties were taken against the teacher merely on the strength of his having been arrested on a homosexual charge. It made no difference that the charges were later dismissed when he had his trial.

Before the teacher had even been before a judge on the matter, the Downey police went to the school where he worked and told the school secretary (not the principal) what had happened. The police also tape recorded a conversation lasting several hours about the teacher’s sex life and sex experiences generally—having nothing to do with the circumstances of his arrest—before they released him on bail. The school authorities immediately forced the teacher’s resignation, and later initiated proceedings to revoke his state teaching credentials. The majority of these liberties were taken against the teacher merely on the strength of his having been arrested on a homosexual charge. It made no difference that the charges were later dismissed when he had his trial.

As far as the laws that have been proposed to remedy these injustices are concerned, not everybody is comfortable. Some who have studied the proposals feel that they will not accomplish the job that needs to be done. These individuals point out that the new laws once voted in will not soon be changed.

Los Angeles attorney, Frank Wood, Jr., who has worked extensively for law reform in California, feels, for instance, that the morals section of the new Model Penal Code is “muddle-headed legislative drafting at its worst.” He contends that “far from being a ‘model’ code it constitutes a long step backward in the fight for sexual freedom between consenting adults.” He takes issue with proposed Section 251.3—which is “loitering to solicit deviate sexual relations.” The new law will read:

A person is guilty of a petty misdemeanor if he loiters in or near any public place for the purpose of soliciting or being solicited to engage in deviate sexual relations.

Wood contends that the section does not help present matters—that it places the freedom of every citizen (whether male or female, heterosexual or homosexual) at the mercy and discretion of the police officer. The statute leaves up to the officer the decision as to what constitutes “loitering,” and what is meant by “in or near.” It even asks the policeman to read the mind of the suspect to see whether he is “soliciting” or wishes to be “solicited” and if this is his wish, whether it is for ‘’deviate sexual relations.”

Mr. Wood also objects to proposed section 251.1 of the Model Penal Code entitled “Open Lewdness.” The section would prohibit a person from committing any “lewd act which he knows is likely to be observed by others who would be affronted or alarmed.” With no clear ascertainable standards of what might be “lewd,” or what might “affront” or “alarm” others, the weakness of this type of law is obvious. Yet laws properly drafted and carefully considered must be enacted to relieve the present situation.

Mr. Wood also objects to proposed section 251.1 of the Model Penal Code entitled “Open Lewdness.” The section would prohibit a person from committing any “lewd act which he knows is likely to be observed by others who would be affronted or alarmed.” With no clear ascertainable standards of what might be “lewd,” or what might “affront” or “alarm” others, the weakness of this type of law is obvious. Yet laws properly drafted and carefully considered must be enacted to relieve the present situation.

As they now stand, our laws can only be considered as being injurious to the public welfare. They invite police spies, suicide, blackmail, damage from wrong court decisions, endless civil litigations; and, as we have seen, they intrude upon the liberties of many innocent persons. It is time to end the discussion and debate on this important question and lift this added shadow that dominates the lives of so many thousands of homosexuals—the fear, the stigma of criminality.

Originally published in the February 1966 issue of Tangents

©1966, 2016 by The Tangent Group. All rights reserved.