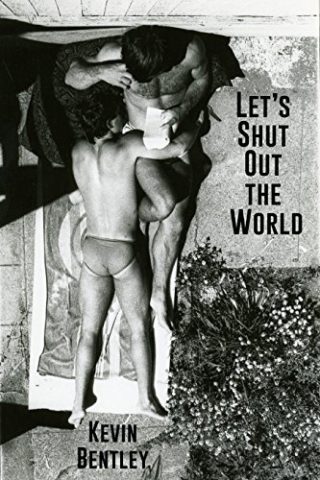

Let’s Shut Out the World

Let’s Shut Out the World

by Kevin Bentley

Published by Green Candy Press

Published 2005

History (memoir)

196 pgs. • Find on Amazon.com

Reviewed by Stephen O. Murray

June 27, 2006.

Kevin Bentley’s (2002) Wild Animals I Have Known was drawn from his diaries written when he was young and wild in San Francisco of the late-1970s’ gay heyday.

Some of his more recent (2005) memoir Let’s Shut Out the World, concern that era, but other chapters (which are essays that can stand on their own, and mostly have done so having been previously published in collections or magazines) provide backstory and accounts of Bentley’s life and amours after the “golden age of promiscuity” (to borrow a good title from a not-very-good book by Brad Gooch).

Bentley is a peripheral character, mostly an observer, in the title story, which is about a lesbian couple’s isolation à deux and the ravages of aging and increasing phobias.

The vignettes of his life, tribulations, and loves are in chronological order. They are glimpses of important relationships (more than events) in his life, beginning with his Southern Baptist homophobic family of birth and the none-too-hospitable environment of El Paso, which Bentley (not lacking in sexual experience, as many other refugees to “gay Mecca” who came to “be gay” had) fled in 1977. The first chapter provides background on his firing his family.

The second focuses on Bentley’s first experience of same-sex sex in seventh grade with a classmate whose family then moved away, and of considerable fag baiting (and being spit upon) by his schoolmates. Cut to college and some young men who found the writing of Ayn Rand sexually exciting (Bentley did not, but was interested in sexually excited—and exciting—men). After a vaguely s&m flirtation with a “fauxhomosexual,” Bentley “attempted suicide with a bottle of Anacin, the put falling in love with straight boys away with other childish things, and, while finishing my B.A. embarked with a vengeance on a two-year course of such promiscuity as El Paso’s couple of back-alley gay bars and two military bases could offer.”

Cut to Sutter’s Mill, a gay bar in San Francisco’s Financial District. Bentley worked in a downtown bookstore. This is the period from which most of Wild Animals diary entries were drawn. Bentley’s writing about that era here has a maturity lacking in them, and an awareness of the cataclysm that followed, which took the lives of two of Bentley’s lovers. (He was infected with HIV after one relationship broke up, but is a lucky “nonprogressor” (to AIDS).) Unlike, for instance, Randy Shilts (attempting to conceal his own sexcapades and ban other men from “promiscuous” sex), Bentley is not plagued by guilt about what some regard as “the wages of sin” and has not turned sex-negative… and never shared the tragic perspective of Andrew Holleran. Some “survivor guilt” is difficult to avoid (as all of us who were sexually active gay men in the late-1970s and are still around can testify).

There is a sardonic chapter on a “widow chaser” (an AIDS hospice worker who specialized in providing comfort to men whose partners were dying, soon-to-be, but not yet “widow[er]s”) and another on the “church of the holy mud” at Chimayo, New Mexico, which one of Bentley’s dying lovers wanted to visit, hoping for a miraculous cure.

One chapter begins “Funny, the way religious nutcases come out of the woodwork to assail you when life’s dealt you a low blow, like sharks to a shipwreck.” This is an unamusing kind of “funny,” one of the ongoing assaults gay men experience (I think that picketing funerals is appalling, and picketing with “God hates fags” completely beyond the pale.)

Bentley is able to laugh at himself (seeing no radical discontinuity between who he was and who he is) and to extend considerable compassion to others behaving oddly and behaving very badly. The book is devoid of self-pity. Bentley has “gai saber” (gay knowledge) and a spirit that is “gay” in the old-fashioned sense of being upbeat even in the face of pain and disaster, as well as the modern sense of “gay” as out and unapologetic about being a man who desires and loves men.

The chapters are well organized; the writing always lively and often LOL-funny. The whole is more than the sum of the parts. The parts fit together (in roughly chronological order). Still, there is not a real flow of them as a single narrative—or putting them together into a portrait of one gay man is left for the reader who is able to avoid being distracted by the portraits of other vivid characters, not least the cranky lesbians in the title story.

Although not lacking in painful experiences, I found the book enjoyable to read, insightful, and frequently poignant.

published by epinions, 27 June 2006

©2006, 2016, Stephen O. Murray