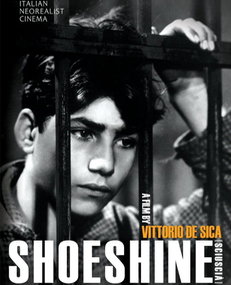

Shoeshine (Sciuscià)

Shoeshine (Sciuscià)

Directed by Vittorio De Sica

Written by Sergio Amidei, Adolfo Franci, Cesare Giulio Viola, and Cesare Zavattini

Released August 26, 1947

Drama (foreign: Italian)

93 min.

Review by Stephen O. Murray

May 11, 2001.

Made for $20,000 in 1946, Sciuscià (Shoeshine) Vittorrio de Sica’s film of two shoeshine boys used by the elder brother of one to fence stolen merchandise, was called by no-one less than Orson Welles “the best film I have ever seen.” He elaborated: “In handling a camera I feel that I have no peer. But what De Sica can do, I can’t do… The camera disappeared, the screen disappeared, it was just life.” The most passionate American film critic of the day, James Agee, wrote that “Shoeshine is about as beautiful, moving, and heartening a film as you are ever likely to see.”

I especially wonder what Agee could have regarded as “heartening.” It seems to me that the film is still moving, but heartbreaking rather than heartening. One of the best and most famous of Italian neo-realist films, I also wonder about the screen disappearing and witnessing “just life.” That is, the story, particularly the denouement seems very operatic to me. Not the opera of monarchs and warriors, but verismo opera. Verismo opera without a soprano, though probably if Giuseppe [Rinaldo Smordoni] sang, his voice would be a boy soprano.

But he doesn’t sing (in any sense). Thinking that he is stopping the whipping of Giuseppe, Pasquale [Franco Interlenghi] “sings,” incriminating Giuseppe’s brother. Giuseppe does not forgive this and does not relent even after Pasquale really is whipped. Giuseppe throws his lot with the bully of the cell in which he is consigned, Arcangeli [Bruno Ortensi].

Pasquale tries to protect another younger boy, who has tuberculosis and is trampled in the fire and riot that accompany the escape of Arcangeli and Giuseppe. More pain and betrayal follows, getting contrived at the end, but the film remains powerful. Heartbreaking, in fact. The reform “school” has transformed the boys from relatively innocent accomplices of criminals into desperate, hardened young men. The destruction of their friendship is only part of the pulverization of their innocence.

The younger (and doughier) of the boys De Sica cast grew up to be a baker. The darker, handsomer then-fifteen-year-old Franco Interlenghi is still appearing in films (other than Sciuscià, the best-known of them is Fellini’s 1953 I vitelloni, in which he played Moraldo). Although De Sica went on to win two more Academy Awards (as director of best foreign films Yesterday, Today, and Tomorrow and The Garden of the Finzi-Continis and to play the title role in Rosselini’s masterpiece Il Generale della Rovere), he never made as compelling a film as Sciuscià.

I was not entirely convinced by the idyllic opening of the film, when the boys are happy with the horse they have bought together. I wonder if the rhetoric which lawyers produce in Italian movies has any relationship to what is said in Italian courts. The cell-block looks like it was lifted from The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari or some other interwar expressionist German film. And the studio-shot finale is a bit pat. However, the loss of innocence is shown convincingly.

I was not entirely convinced by the idyllic opening of the film, when the boys are happy with the horse they have bought together. I wonder if the rhetoric which lawyers produce in Italian movies has any relationship to what is said in Italian courts. The cell-block looks like it was lifted from The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari or some other interwar expressionist German film. And the studio-shot finale is a bit pat. However, the loss of innocence is shown convincingly.

There is no lecturing, the music is only occasionally a bit hectoring, and the dialogue is far less important than what is written on the young non-actors’ faces.

How homoerotic is it? Early in the film the two boys awaken in a bed of straw in the stable where there horse is kept. This seems completely chaste, and the contact in the reformatory is not overtly sexual. Pasquale is clearly jealous at his place being appropriated by the spectacularly misnamed and unworthy Arcangeli.

Carson McCullers famously said that there is always one who loves and one who is loved. Pasquale is clearly the one who loves, Giuseppe the one who is loved and who draws older protectors.

We have De Sica’s words that homoeroticism was not intended. In a 1971 interview included in Encountering Directors, he was asked about the theme of “homoerotic love among adolescents” not being developed and answered: “Because it revolted me.”

I don’t know that we should believe what someone says years later more than what we see in the film. It seems to me that the male nudity is entirely gratuitous (that is, it does nothing to advance the plot or character development). The fistfight that follows in which Pasquale knocks down (and out) Arcangeli seems to me to be about pairing with Giuseppe. The anguish at the end and the riding (by each pair) of the horse together is suggestive. As in hugging a motorcycle driver, the horseback embrace is probably intended as “innocent” by De Sica, but read differently by me—with my own memories of riding to school clasped to my schoolmate’s backside.

first published on epinions, 11 May 2001

©2001, 2016, Stephen O. Murray