A Separate People whose Time has Come

by Harry Hay

as published in Gay Spirit: Myth and Meaning

The HIC is grateful to Mark Thompson and White Crane Books for permission to publish this historic essay. This material is copyright protected and may not be reproduced without permission from the author and publisher.

We have been a separate people, drifting together in parallel experience, not always conscious of each other … yet recognizing one another by the eye lock when we did meet, down the hundred thousand years of our hag and faerie history (hags being the proud and free women of the wild-wood in the word’s original meaning), here and there as outcasts, here and there as spirit people who mysteriously survived close contact with violent nature forces, in service to the Great Mother—acting as messengers and interceders, shamans of both genders, priestesses and priests, image makers and prophets, mime and rhapsodes, poets and playwrights, healers and researchers. And always almost all of them were visionaries, almost all them were described from time to time as speaking in tongues and in voices other than their own— possessed, as it were; always almost of them were rebels, against the straitjackets of the hetero(sexual) conformities controlling and manipulating the given status quo—whatever the regimen and wherever the region. A separate people coming together—one by one—down the hundred thousand years of our journey, we began to discover slowly … hesitantly … painfully … commonalities we share from the heterogeneous bloodlines that had discarded us that:

We have been a separate people, drifting together in parallel experience, not always conscious of each other … yet recognizing one another by the eye lock when we did meet, down the hundred thousand years of our hag and faerie history (hags being the proud and free women of the wild-wood in the word’s original meaning), here and there as outcasts, here and there as spirit people who mysteriously survived close contact with violent nature forces, in service to the Great Mother—acting as messengers and interceders, shamans of both genders, priestesses and priests, image makers and prophets, mime and rhapsodes, poets and playwrights, healers and researchers. And always almost all of them were visionaries, almost all them were described from time to time as speaking in tongues and in voices other than their own— possessed, as it were; always almost of them were rebels, against the straitjackets of the hetero(sexual) conformities controlling and manipulating the given status quo—whatever the regimen and wherever the region. A separate people coming together—one by one—down the hundred thousand years of our journey, we began to discover slowly … hesitantly … painfully … commonalities we share from the heterogeneous bloodlines that had discarded us that:

- That it is not in our natures to be territorially aggressive, when the heteros around us would casually kill one another simply to become kings of the mountain.

- It was not in our natures to be competitive—we only yearned passionately to share with one another instead.

- It was not, and is not now, in our natures and never part of our dream, to want to conquer Nature … we were always the shy kids who walked with clouds and talked to trees and butterflies.

- Whereas heteros believe that spirituality requires the fervent denial of carnality … for us gay folk the preprogrammed instinctual behaviors triggered by, and thus awakened by, our early sexual and sensual discoveries constitute for us the gateway to the growth of spirit in heart and mind.

The above characteristics seem—even today—to signal the potential of new behavioral directions for the whole species. Appearing in us gay ones persistently, millennia after millennia, we propose that they have always carried the promise of adding sweep and scope to the capacity of the human species to adapt to changing evolutionary circumstance. Half a century ago, the biologist Julian Huxley pointed out that no negative trait (and, as we know, in biology a negative trait is one that does not reproduce itself) ever appears in a given species millennia after millennia unless it in some way serves the survival of that species. And now, perhaps, we are already discovering the no-longer-so-shadowy outlines of the DNA-related contributions we gay folk have been capable of all along … contributions we now must share in the service of that survival.

On our small planet, it is terrifyingly apparent that each hemisphere is riddled and wracked to it very foundation by spiritual contradictions. It must be glaringly clear that the traditional hetero male-dominated subject-object consciousness is bankrupt worldwide to the point of becoming lethal. A new consciousness must surface to replace it, and I propose that we gay folk, who Great Mother Nature has been assembling as a separate people in these last hundred thousand years, must now prepare to emerge from the shadows of history because we are a species variant with a particular characteristic adaptation in consciousness whose time has come!

Only in the last forty years have gay people in America begun thinking collectively of themselves as “we who have been different from the heteros around us all our lives.” The process by which we began this reinvention and the self rediscoveries we have made along the way are curious and instructive. In the three years of the first Mattachine experience, from 1950 to 1953, we looked at ourselves as a particular community drawn from all races and classes—found ourselves good, forward-looking people with undercurrents of a collective point of view very different from that usually experienced in the above-ground communities around us. Chafing under the arrogant hetero stereotype that forbade our people to be seen in any way other than as willful, perverse heteros performing unnatural, therefore criminal, acts, we figured that, if we insisted on calling ourselves by a term they didn’t understand, the media would have to ask us what it meant; and we—then—would be able to define and characterize ourselves, for a change. It worked — somewhat! By the persistent use of the term homophile (instead of the hetero-designate gemixtepickle homosexual) we educated American public opinion to perceive us no longer as merely perverse performers of criminal acts but as persons of a distinct sociopolitical minority … albeit a psychologically sick minority until we finally got that cleared up in 1973, the year the American Psychiatric Association removed homosexuality from its list of mental disorders. Also, here in Los Angeles, in those incandescent first three years, 1950 to 1953, we did set before ourselves a series of questions:

- Who are we gay people?

- Where do we come from, in history and in anthropology, and where have we been?

- What are we for?

Because the basic perceptions in modern science, that made it possible for us to project this third question at all belong themselves to the mid-1950s, the pieces of the puzzle accumulated more slowly. First, we would have to survey and re-survey the whole ground, the chronicle of consciousness as it emerges into history from myth and legend and folk play, so that we could begin to sense our gay selves disentangling from the shadows between the lines. In San Francisco at the three-day retreat for gay activist men and women, as well ministers and scholars, in August 1966, I found myself inventing a gay concept of love as “the giving or granting to that other the total space wherein he/she may grow and soar into his own/her own freely selected fullest potential.” The ministers as a group were quite unprepared to discover that, in contrast to their own experience within their own usual hetero constituencies, the gay community generally had little difficulty in accommodating the concept of “non-possessive” love.

In late May 1969, while attempting to explain Whitman’s poem “The Multitude,”

Among the men and women the

multitude,

I perceive one picking me out by

secret and divine signs…

I suddenly saw, (as Whitman must have seen, even as he fashioned his poem) that he and I looked through a window on the scene quite different from that perceived as “being all there is” by the heteros hurrying on either side of him and, yesterday, on either side of me. And even as I said that, I realized with a sudden rush that I’d seen through that gay window all my life as, obviously, Whitman’s poetry gave witness that he had seen through that window all his life. A year-and-a-half later, I would propose that what we saw through that gay window might be generalized as “gay consciousness.”

Reinventing ourselves has been a combination of cautious tippy-toe stuff and dizzy leaps into scary insights, each leap and breakthrough being checked against the way it sound — the way it floats — at a gut level: the way it harmoniously resounds at the diaphragm. If it feels right for dykes and faeries, we stand on it to see if areas of our vision before—usually in shadow, where not even totally obscured—may now be partially visible or observable. A lot of our insight have turned out to be sudden recognitions of things past that we could not have seen while we were still in them or still part of them. One day during a rap in 1974, I suddenly remembered that, when I was in the fourth grade, the boys at school would tell me I threw a ball like a girl, but Maryellen Fermin and Helen Johnson said, “No, you don’t throw a ball like a girl. You throw it like a sissy!”

In that 1974 rap, with my newly discovered gay window offering flashes of insight, I was seeing that while these long-ago boys were saying that I was doing things in a non-masculine therefore feminine fashion—“After all, what else is there?”— the girls equally had been saying, “No, you’re not being feminine. You’re being…other. Not masculine—okay! agreed! But not feminine either. Other!” So, also in 1974, looking back at that incident through the lenses of a fifty-year-old memory, I realized how dazzling a witness it was to demonstrate just how radically different the hetero women’s window on the world could be from the traditional macho rant that never stops: “Everybody knows that women — when they’re making any sense at all — are thinking exactly the same as men!” Yet even as the first enormous momentum generated by the 1970s, behind the ERA, faltered, gentle hetero men began appearing for whom the macho credo was no longer acceptable: I found myself defining them as nongays. Though it was clear in many respects that gay windows on the world continue to be as opaque to these nongays as the hetero male-derived windows had always been opaque to us, faeries and hags alike; nevertheless, it was equally clear that new dimensions in gender-related ways of seeing were being sought after that were not yet materializing.

Four years earlier, when I was looking for a word to represent neither masculine or feminine, I used the word the hetero bully boy had used to describe me as they saw me all those years ago. “Fairy,” they called me, “not-masculine/not feminine—fairy.” Only now that I’m grown up and have become a proper queer, I gussy up the spelling to make it f-a-e-r-i-e. But when the little bully boys has used the word fairy, they would spit it out venomously! Why was the not-masculine-but-equally-not-feminine boy they saw through their hetero-male windows so hateful in their eyes? I would suggest it was because he didn’t fit the conformity by which they knew themselves and each other, like wolves in the pack or rats in the nest. If your tail bends wrong or you don’t smell right, you’re driven out of the pack or you’re shoved out of the nest. Because many of us, even as little kids, assumed we were free to follow our inner motivations to express ourselves the way we wanted to appear, we probably had slipped out of the conformity. And when we grew up, many of us appear to have gone on being guided by that same mysterious inner vision to explore our freedom to be!

As adults—though similar to our hetero counterparts physiologically, we gay folk emotionally, temperamentally and intellectually, or, in a word that subsumes all three, spiritually — some of us may be a combination of both hetero masculine and hetero feminine, but mostly we are a combination of neither:

- It is from this spiritual neitherness, evident in our capacity to fly free from historical conformities and prejudices, evident in our capacity to invent in the very teeth of nullifying rules and regulations, that our contributions come.

- It is from this spiritual neitherness that we draw our capacities as mediators between the seen and the unseen, as berdache priest and shaman seers; as artist and architects; as scientists, teachers, and as designers of the possible — mediators between the make-believe and the real, through theater and music and dance and poetry; mediators between the spirit and the flesh, as teachers and healers and counselors and therapists.

- It is from this spiritual neitherness, as the sissies and tomboys of the schoolyard, that the kids who grew up (each the only one of her/his kind he/she thought) on the outside of the chain-link fence looked in and observed both sides of the hetero social experiences of boy/girlhood, teenhood and adolescence they had thrust us away from and then had shut us out from.

- It is from this spiritual neitherness that we draw our capacities to be to see them as they can never see themselves, we draw our capacities to be to them as a nonjudgmental mirror, giving them back to themselves through theater, dance, music, poetry and — above anything else — through the affectionate mockery of camp that expresses itself in healing laughter.

When we begin to truly love and respect Great Mother Nature’s gift to us of gayness, we’ll discover that the bondage of our childhood and adolescence in the trials and tribulations (dark forests to traverse with no one to guide us) of neitherness was actually an apprenticeship she had assigned for teaching her children new cutting edges of consciousness and social change. In stunning paradox, our neitherness is our talisman, our faerie wand, our gift we bring to the hetero world to

- transform their pain to healing;

- transform their tears to laughter;

- transform their hand-me-downs to visions of loveliness.

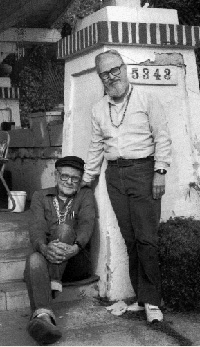

John Burnside

In 1975, my beloved companion John Burnside and I produce an essay—published in that summer’s issue of RFD, a grass-roots publication for rural gay men—to commemorate the silver anniversary, on July,10, 1950, of my finding my first recruit to what would become the first Mattachine Society.

In it we said, “Homosexuality is a genetic means of high importance in preventing … disaster to the race, as we shall here endeavor to show, by acting to preserve variety and diversity in the range of traits inherited by each generation … To produce such an effect, homosexuality must somehow produce a force in aid of human beings having quite different qualities than those favored and most rewarded by our society—the dominant, aggressive and manipulative men and women—in the competitive race for survival.”

The giant leap in gay consciousness, the blinding flash through the gay window that would be a revelation of what that “force” might be, came—for me—in spring 1976. In a letter, I was explaining how—when we thought about ourselves as pre-teenagers during the bleak years when we thought we were the only ones of our kind in the whole world—we would naturally be thinking about ourselves as subjects. And then, suddenly, when we somehow discovered that there might be another just like ourselves somewhere, and we started to think about—and fantasize about — him, we would have been perceiving him in exactly the same way as we were perceiving ourselves. We would be perceiving him as if he were also subject.

In the letter I had gone on for about two more pages—when suddenly reality burst in my head like skyrockets. What had I just said? This was the link in the chain I had been trying to grab hold of for thirty years. Of course, I had perceived my fantasy love as subject — in exactly the same way as I perceived myself as subject, in exactly the same way I had always perceived my teddy bear as subject, in exactly the same way as I had always perceived the talking trees and the handsome heroes in my picture-books as subjects.

Oh, I knew that all the other kids around me were thinking of girls as sex objects, to be manipulated to be lied to in order to get them to “give in”—and to be otherwise treated with contempt (when the boys were together without them). And, strangely, the girls seemed to think of the boys as objects, too. But that was it! Writing the letter now, in 1976, I was remembering vividly how, in that long-ago fantasy, he whom I would reach out in love to was indeed projected as being another me — and the one thing we would not be doing was making objects of each other. Just as in my dream (which I would go on having for years), he’d be standing just before dawn on a golden velvet hillside … he’d hold out his hand to me to catch hold of, and then we would run away to the top of the hill to see the sunrise, and we would never have to come back again because we would now have each other. We would share everything, and we’d always understand each other completely and forever!

From that memory, which, once unleashed by that incandescent leap-into-speculation, continued seeming to validate itself ever the more strongly with each new adventure in the projection, came a new rush—a new “high,” the sudden flooding from a second radiant memory. This would be the time when I actually met such an other, a boy I had been dreaming about for nearly a year. Between us at the instant of first eye lock, it was as if an invisible arc of lightning flashed between us, zapping into both our eagerly ready young bodies total systems of knowledge — instances of ethological “triggerings” such as the inheritable consciousness that Dr. Ralph Sperry of Cal Tech was, in 1979, rewarded for discovering.

Suddenly we both were quivering with overpowering preprograms of knowledge and behaviors of which our gay flesh and brains had always been capable of but never, until that moment of imprinting, had actually contained. Now, through that flashing arc of love, we two young faeries knew the triggered tumult of gay consciousness in our vibrant young bodies—in ways that we in the moments before would never have imagined and now would never again forget, for so long as we lived. And this — in ourselves and, simultaneously, in each other — we also knew: subject-to-subject.

In the beloved fairy stories of our childhoods, the fairy god-mothers—or, if we were lucky, the handsome fairy princes—would give the chosen subject of the story “talisman”: The talisman, in turn, unlocked secret treasures or gave the person holding it the power to fly, or made visions and wonderful dreams come true. New phrases such as gay window on the world or gay consciousness and new concepts such as subject-subject consciousness seem also to be talismans, because both Faerie brothers and hag sisters, upon hearing such phrases and concepts for the first time, keep constantly finding themselves brimming with new visions and spiritual breakthroughs that they’d been bottling up inside themselves for years, maybe for a lifetime—because, until the moment of receiving the talisman, they’d had no shining words to contain the image, no metaphor for the ambient new idea, no frame of reference for a new multidimensional way of perceiving.

Now—all at once seeing themselves as subject-subject people in a subject-object world—they, for the first time, began to comprehend the nature of their dilemma s well as the far-reaching widths and depths of their oppression. They found themselves appreciating, for instance, how the loving care with which one’s mother and siblings pursued total conformity could be absolutely lethal for their faerie selves. So we, as subject-subject people, may also begin to wonder why in the world we continue to imitate hetero behavior at all when we very well know, with every breath we draw, that such behaviors suit us not at all. After all, we aren’t heteros. And when we do imitate them, we usually do it badly—we either overdo or we underdo. Mostly, to perfectly candid, we overdo.

The talisman of subject-subject consciousness immediately explains why faeries so often have had such constructively loving relationships with hetero women. It would not be because of the hetero-male stereotype that we are half-women ourselves and so are accustomed to seeing ourselves as objects, similarly to the way hetero women know themselves to have been traditionally perceived and used by their menfolk. It would be because we faeries see our women friends as subjects in the same way as women perceive themselves as subjects; and the women know this and luxuriate in the mutuality of sharing. Indeed, the women of the women’s liberation movement are aching to learn how to develop some measure of subject-to-subject relationships with their men. And they wonder why we, who have known the jubilations of subject-to-subject visions and visitations all our lives, have neither shared nor even spoken.

Of course, we haven’t as yet spoken because we haven’t as yet begun to learn how to communicate subject-subject realities even to each other, using our traditionally inherited hetero male-derived-and-developed subject-object language in our traditionally inherited hetero male subject-object world. The catalyst of spiritual crisis within the gay movement has brought many gay men face-to-face with the appalling dichotomy between, on the one hand, the nurturing sensitivity and concern for each other in a mutuality of sexual intimacy that we all profess to be seeking and, on the one hand, the nurturing sensitivity and concern for each other in a mutuality of sexual intimacy that we all profess to be seeking and on the other, the desolation and alienation from self and from each other that more often takes place as we make sexual objects of ourselves and of each other in pursuit of the traditional and expected behavior in bars and baths. How might we apply subject-subject consciousness to gay sexual sharing? For starter, we might try enjoying each other’s enjoyment. If you allow me to tune in, non-judgmentally, on your enjoyment, whatever that might happen to be in your consciousness as we approach each other, as I hope you will, in similar fashion, tune into my enjoyment—it could follow that it wouldn’t matter whether you were large or small, or fat or thin, or old or young, or soft or hard: We would be intimately tuned into sharing each other’s enjoyment as subjects, each to the other, and each to himself as well. At this point it should become apparent that our previously unexamined habits of imitating heteros, not only in their sexual myths and taboos but in their possessive and objectifying sexual behaviors as well, are really for us not only unsuitable but quite irrelevant.

Through the interchanges of mutual pleasure into which subject-subject sexuality catapults us, we can discover one of the key characteristics that marks us gays as a separate people. In the best scientific thinking produced by the subject-object world of the traditional hetero male in the nineteenth century, hetero coupling parallels the still-valid scientific metaphor of electro-magnetism —that of supreme complementarity, wherein unlikes attract and likes repel.

But in the world of our gay sensibilities, in the subject-subject consciousness by which we have perceived from as far back as any of us can remember, we have not sought nor wanted to find our complementary opposites—we sought instead others like ourselves.

Subject-subject folk do not seek to possess or to manipulate; instead they seek to share, to slip off the impermeable separations of ego and meld collectively into the lover, or lovers, perceived as subject. We faeries and hags think of ourselves as subjects, as whole persons—self-reliant, independent, and whenever possible, free people: We seek others as whole and as self-reliant and as independent as ourselves. I do not seek someone who desires to lean on me: I seek someone who will face forward with me, shoulder-to-shoulder, who will circle with me, like two great soaring eagles dancing together at the edge of the sky—each capable of being quite total and complete in himself. We seek supplementarity: In the new world coming of subject-subject consciousness, in new dimensions of science where answers to many levels of new questions now being raised have not yet cohered into the eagerly sought but still elusive superseding metaphor, likes attract and unlikes repel!

A separate people, we must begin to wrench ourselves away from imitating the subject-object heteros in all ways possible, besides just the lovely and intimate ways of sharing ourselves with each other. Looking through the window of our gay consciousness at the gay marketplace, you see at once a whole host of hetero-imitative entrepreneurs—precisely because they conceive of themselves as in lifelong competition (each with the hetero he or she is imitating)—engaging themselves endlessly in tug-of-war games of domination and submission. The loftiest hetero ideal of governance—democracy—is in the final analysis, the domination of minorities by a majority; a tyranny of the majority, if you will. If anyone knows the agonies inflicted, the lives misshapen and distorted and destroyed by the hate-filled oppressive majority, which a democracy usually is, it would be the black community, the women’s community, the gay and lesbian community.

In reality, all the hetero ideals of the democratic procedure, these jewels refined at terrible costs from the millennial bloody battlegrounds of relentless hetero competitions, must be exposed as conditions of subject-object thinking: ideals such as fair-play, the Golden Rule, equality, political persuasion, the give-a-little-take-a-little of parliamentary reconciliation—and so democracy. In each case, a given person is the object of another persons’ perceptions, to be influenced, persuaded, cajoled, jaw-boned, manipulated and, therefore, in the last analysis, controlled. Subject-object consciousness, the epitome of the hetero-male competitive reality, has carried the human race successfully on a long and difficult ascent, to be sure. But perhaps the time is at hand for humanity to discover it ultimately obsolete.

In the forty years we have been engaged in reinventing ourselves as a separate people, we have learned many of the things we are going to need in relating collectively in subject-subject terms. For example, we seem to relate best in work groups of say, fifteen to twenty-five: we’ve noticed that work groups flow best in circles where each participant is free to speak in turn through the employment of a talismanic object passing from hand to hand. We’re we now to transform such circles so that each participant reaches out to relate to his/her neighbor, co-joined in the shared vision of that nonpossessive love we’ve glimpsed through our gay window, we might develop for the first time in history a true working model of the loving, sharing consensus of the whole society. In a community, or a community of communities, functioning through such consensus circles, all authoritarianism—of course—would vanish: For, in such circles, who would be head and who the foot? The participants would nourish, sustain, and instruct each other.

So let us begin. There is so much healing to be done, so much mending and so much tending; and time may be shorter than we know. Out of history we emerge

A separate people whose time is at hand.

Out of the mists of our long oppression,

We bring love for ourselves and for each other,

and love for the gifts we bear,

So heavy and so painful the fashioning of them,

So long the road given us to travel to bring them.

A separate people,

We bring a gift to celebrate each other;

’Tis a gift to be gay!

Feel the pride of it!

A separate people,

We bring the gift of our subject-subject consciousness

to everyone,

That all together we may heal our planet!

Share the magic of it!

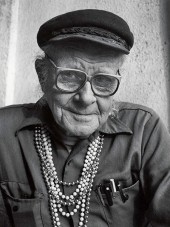

The Tangent Group thanks Jack Clark for his typing of this manuscript. Promotional portrait of Harry Hay by Robert Giard.