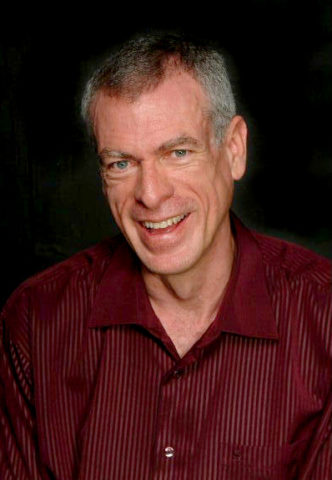

Interview with Steve Schalchlin

Interview with Steve Schalchlin

for an article in the May 2017 issue of A&U Magazine

by C. Todd White

This interview with Steve Schalchlin took place on Friday, February 3, 2017. It began at 8:00 a.m. Pacific Time. Todd White was calling from Las Vegas, Nevada, and Steve was at his home in New York.

Todd’s comments are in italics. This is an edited excerpt from the full transcription. The occasion for the interview is Todd’s article on Steve to be published in the May 2017 edition of A&U Magazine.

8:00 in the morning on Friday morning, and the date is Friday February 3rd.

[phone rings]

I’m sorry, but you are one minute late. Mr. Schalchlin is not available.

Aww, man! Well, I had to get coffee.

Well, that is okay then. So long as it is coffee.

I’ve been reading the old very first entries in your diary.

Oh my God!

Which makes me wonder, do you remember when you first heard the word “blog”?

It was about three or four years after I started.

And you probably had an a-ha moment like that is exactly what I’d been doing, why didn’t I think of that word myself?

Yeah. There had been some journals online that people had started to do. But when I began mine I didn’t actually, I hadn’t actually read anything on the Internet yet. I had looked at a couple of things, but mostly I had looked up how to write HTML because I knew I wanted to keep this diary because my focus was strictly on trying to update my family and doctor.

Right.

So that was my strict focus. I wasn’t trying to create a new art form. And then I met some people and made friends around who were also journalling. And so at the time I thought I was stepping into a very deep pool, of other journalists, because you always feel as if you’re 100 years behind everybody else.

Well you’ve been ahead of the curve in a lot of ways. I just read that The Last Session was one of the first, if not the first productions to be live streamed?

It was the first professional, like equity production that was live streamed. I’m sure that there were like little unknown shows, but we had a fan who worked for a large company that had T1 line. And he said “Hey, I could hook you guys up and we could probably broadcast this thing live.” And everyone was still on dialup back then, so I don’t know that it was much of a picture.

Well isn’t it amazing how sometimes things that you think are just common sense that you think other people would have thought of or had been thinking at the same time end up to be quite novel?

Yes. It all just seemed very natural to me. I think that’s because in my life before this, I had worked at the National Academy of Songwriters. Any my job was creating programs, educational programs for songwriters. And the main thing I was facing and confronting was: How do I publicize these things? And at the time, it was pre-Internet, but it was like Windows 3, I think. So the graphical user interface had just begun. And one of our board members got us a computer for the office, so I was doing cut-and-paste of newsletters and handing things out on the corner and trying to mail things, and as soon as the Internet popped up, and I realized I could broadcast myself over the whole planet by starting this journal. It just seemed like, of course! It’s just extension of the work I did at the National Academy of Songwriters, but I’m doing it for myself.

At what point were you able to keep track of how many people were tuning in?

That came a little bit later, maybe about a year later. I started keeping a track, but then I shut down the counter. Because I found myself trying to write for the masses and trying to see, you know like clickbait. I had anticipated clickbait. And I started to realize that if I kept writing in order to get more clicks, then I’m not really staying true to myself, and it is messing up my creative source. So I shut down the counter and said, “I’m going to write for the reader. It doesn’t matter how many there are, all I know is there is one person reading it at a time, and that is all that really matters: that person who is reading it at that moment.”

Did that carry over into your attitude about your work and your music?

Well actually it did. And that was actually… When I started to write, and that was before I started writing this diary, when I started writing the songs, I had been running a lot of songwriting workshops in Los Angeles as part of my job. And I noticed that when songwriters would bring in their material, and I would have workshops and I would have record industry people and producers in to listen to their tapes. Whitney Houston was big at the time for accepting outside material, so people would try to write a song that Whitney Houston would sing. Consequently, all of their music was really generic because they were going for a larger audience.

So when I sat down to write The Last…This literally went through my head. When I sat down to write the first song, which was “Connected,” I said to myself, “I’m going to write a song that no one will get. That no one will cover. I’m going to write a song that nobody but Jim and a few family members will even get remotely.

And that became the most universal song that when I sang it for people, their jaws dropped. And everybody thought I was singing about them. And a lightbulb went off in my head and I went, “Ahhh. If I write very very specifically”—and you probably know this as a writer yourself—“if I write a very specifically about my individual feelings and experience, and not worry about whether anybody else will get it, it will become more universal than if I try to write for everybody.” So I think I extended that thought into the diary.

At what point, or did you from the start, realize that your diary was another act of creativity?

I think it was when I began to get emails from around the world.

Wow.

Nowadays we think of that as commonplace. Back then, I can remember some very specific times. The most emotional one was when this lady from Washington, a perfect stranger, wrote me and said—in the diary I had been writing about how I was having a very tough time, which was making me angry because I was sick. And I yelled at my doctor that day, and I wrote in the dairy how I screamed at my doctor, and I screamed at Jim, and I was just yelling at everybody and for no cause except for the fact that I was sick.

And this lady told me that she had been taking care of her husband who also was living with AIDS, or dying of AIDS really. And she said, “I cook for him. I change his bed pans. I’m changing IVs. I’m cleaning the sheets, I’m breaking my back and doing absolutely everything that I can do, and all he does is yell at me.” She said, “I feel like I’ve been living in hell! And when I read your diary, and I read what happened to you that day, because you were so candid about your own weaknesses and what was going on, I felt like the weight of the world lifted off my shoulders because I made the connection. Oh! When you get sick, you get angry. He was throwing things at me and I realized, he’s not mad at me. I’m not doing anything wrong. It’s because when you get sick you get angry.”

And that is the phrase she used: “The weight of the world lifted off my shoulders.” And she thought, “All I can do is what I can do.” And she said, “Thank you very much.”

And then I remember some kid in the outback of Australia was one of the earliest responders, and he was some 13 year old kid in the outback, and we had these wonderful conversations back and forth. And when I got to—the ones I was not aware of, when I was finally invited to the Harvard School of public health by a reader who was also an instructor there. And he said, “I have printed out your entire diary. And I’ve given it all of my students. And they are, and I want you to come and talk to them.”

So I came up to this class with about 30 or 40 students were in there, and they were from all over the world. And what they had told me, some of them told me that in far-flung corners of the earth, because I was being very candid about what was working and what was not working for me, they said that was the only information that they were getting about how to treat their own patients.

Wow.

Because there was no other information available. Really all of this information was confined to support groups. Where people were chatting with each other. And I had joined some of the early online bulletin board services and I was getting information from them, and I was kind of relating some of that in my diary. I was trying colloidal silver and was trying this herb, and this and that thing, and each one that I reported—each one of them were taking what I had and were using mine as a case study for treating their own patients. And this was told to me there in the class. And I was like, shocked. I didn’t know that there were doctors and nurses and caregivers and professionals who were reading my diaries because it was one of the few places they could get direct information about AIDS.

I was going to ask how in the early days people found you, but it sounds like it was kind of snowballing in a way.

There were still search engines. There were early search engines that they could type in the work AIDS, and mine was one of the only places that actually popped up. So that’s how people were able to find me in the early days. It wasn’t Google, but it was something. And also there were these groups that scanned a lot of the early pages that would have like a web site of the day, like there was a thing called the “cool website of the day,” it all sounds like this bedroom, you know, bedroom craft word almost: “Oh look there’s a cool site!” And I remember when I first spoke to a college class. Only about a third of them even had email.

Wow.

Nowadays we are practically born with an email account. But um someplace called “Cool Site of the Day” made me the cool site of the day, and that really brought in… I still had my counter up at the time, and so that brought in a lot of listeners from all over the world. So now I’m getting emails from Costa Rica, and Puerto Rico, and Europe, especially Australia and Britain. English-speaking countries started to write me and ask what was going on and asking for information. I sort of became a one-man information source for a lot of people. And then I was able to turn them on to other places where they could get information.

Well you know the feminists have saying that the personal is political, and I guess you are proof positive of that, huh.

Absolutely. And I sometimes think our best work is accomplished when we are not trying to accomplish something big. But we are trying to just do something personal and small, and it is the same way in songwriting. If you focus down rather than focusing up, you can end up mattering to people a lot more.

Oh I like that. That is actually encouraging on a lot of different levels. I was… kind of jumping track a little bit, What is Acoustic Underground?

Acoustic Underground was a monthly series that I was a co-producer of, or lead producer of, in Los Angeles, to help discover acoustic songwriters. At the time the music industry was mostly big-hair bands. It was, you know, spandex and big hair. And so the songwriters in Los Angeles… there had been a few acoustic clubs, but the last one closed about that time. It was called The Breakaway. And here’s another one of those unintentional things. We set this up with Paul Zollo who is a noted author of many books about songwriters. Paul was the editor of our newspaper at the time, and he was doing an acoustic show. And he says he came up with the title, and I thought I came up with the title, it doesn’t matter. But I looked at it as a way to showcase songwriters where I didn’t have to have a half-hour set up between every act. I said, “If you can walk on the stage, plug in your guitar, and start singing, you can be on the show if you can pass the audition process.” And the audition was just send in a tape and we’ll listen to it.

So that kind of started a revolution in the music industry on a very very fundamental level because people had been so plugged in that they didn’t think that a person with a guitar could make much of a difference anymore.

What was Paul’s last name again?

Zollo. He was also one of the producers and he says he thought of the title, which is fine with me, I don’t really care. I don’t care about credit. But I’m the one who brought it to The Troubadour and made a big industry event out of it. So now we had big industry people coming in to come in and hear all of these great singers and songwriters. And there were a lot of people that came out of that scene that was created around Acoustic Underground that people, uh, Dan Bern, he’s a big folksinger now, and he was one of my discoveries. Along with Dan Brown, who was a songwriter at the time and has now written DaVinci Code.

Oh wow. I didn’t know that.

Yeah. And he came to town as a songwriter but he was, what he really wanted to do was write books. He was a writer. So he was one of the people I discovered along the way. And it was, it was a fun time.

Is it still in action?

No. Because the National Academy of Songwriters folded.

Oh.

After I left. I’m not saying that they folded because I left; it went for a while after I was gone. But they finally were absorbed into the Songwriters Guild, which was a different group. But for a long time there, that was my job was to keep the doors open on that place because it was kind of a failing institution. Um just through good old hard work, I kind of helped to rebuild the place and get money in and got us back solvent again and kept it running for a while.

How did you start in music? How old were you when you first put your fingers on the keyboard?

Seven years old, when I took my first piano lesson. My father’s a pastor in a Baptist Church. My mother played piano, and so she thought I should learn how to play, so I started to taking lessons. Which I hated. Practicing, which I hated and still hate to this day. But then we moved to a very small church, and I had to play the piano for the congregation. And that was really what got it into my bones, was having to play for the congregation. From the age of 10. And I never liked the piano at all because I always loved guitar much better. And then came the day when Paul McCartney played the piano on The Ed Sullivan Show. And that was it for me. That is when I went, “Oh, the piano can be cool!”

Oh wow.

I think, it was probably “Hey Jude.”

Oh wow. I remember when that song came out.

Yeah. And there was a close up on him at the piano—I can see that see the video in my head right now. And I went, “Oh, Look! The piano can be cool…”

How many instrument can you play?

It used to be only the piano, but after last year I can now play piano and guitar. [Laughs.]

What happened last year?

I decided at the age of 62 that I was going to learn how to play guitar.

Was it an easy transition?

It was easier than I thought it was going to be. Um, most people, when they learn an instrument, don’t know anything about music. So they are learning two things. So they are learning about guitar but they are learning about chords and chord structures and all of that stuff. I already knew music. So all I needed to know was how to make the chords. All of those years of watching other guitar players play and going like tchic-tchick-tchick-tchick-tchick on the guitar, which you can’t do on the piano, the minute I had a guitar in my hand I could make a chord. I knew exactly how to strum it, and I felt like fish to water.

Have you performed live on guitar yet?

I have. I have. In fact I did my first gig five days after picking up the guitar.

[Laughs.]

Part of the songwriter groups that meets on Monday nights, we have to deliver a new song every week. Which is why you see me posting songs all the time on Facebook, that nobody listens to. And, um, because nobody listens to anything anymore, we have too much choice. But they were doing a little outdoor—this was last year. They were doing an outdoor gig at a park, and everybody got two songs, and I didn’t want to haul a keyboard. And a friend of mine had give me an old guitar that sat in my closet for about a month. And I thought, alright. I have this song here, I have two songs here that only have a couple of chords in them. I bet you I can figure it out well enough to do the gig on Saturday. So I started on Monday and on Saturday I did the gig. I wasn’t great, but I did it.

Hm. I want to… going back to some of my questions about your early days, the finances. I was reading about how some of your meds cost about $800 back in the ’90s which even today is a formidable amount of money, and how the insurance company dropped you. How did you pay for everything?

Well I had to get help. I went to a lot of different agencies and I sat hat in hand. There were music industry places I could go, there were government places I could go, and uh, part of this is hard to talk about because I’m always afraid they are going to take it away from me. But I just had to, I had to do whatever I could, and mostly I had to depend on the government and other baseline help. There were clinics, for instance, that I could go to that were servicing other people who had limited income. So I’d go to a clinic and I’d sit next to hookers, and other people like that, and I would just stand in line and try to do my best to do what I could.

This is not a question for the article, but I…maybe I’m…do you ever get angry that so much money is being made by the pharmaceuticals and the medical industry off of people who are suffering?

I don’t know how else they can make more drugs. I haven’t really looked at their books. You know, because of all of the government regulations, and Andrew Sullivan writes about this too, but they spend hundreds and hundreds of millions of dollars to develop one drug and they are not sure it’s even going to work.

I was invited to MERCK at one point and I met the guy who created Crixivan, that saved my life. And he went through the whole development process with me and told me how they have to jump through these hoops, for good reason. And it’s even more stringent than that because not only do they have to have a drug that is effective but they have to have a drug that is effective that people will actually take. And if it’s injectable, people will generally not take it. So they have find a way to get the drug down to a pill form. And in order to get it to a pill form, they have to get it through the liver. And to get it through the liver they have to—you know. It’s like this long unending trail of how to get a drug that is deliverable, much less a drug that is effective.

So between you and me, I don’t really… I don’t know. I think it is a miracle that we have these drugs at all.

That’s very very true. And, at what point…. your viral load now, is it undetectable?

Yes.

When did that happen? And how did you feel?

Well it began to happen at a time in, you can go back to the diary on this, it is in spring of 1996, and there is kind of some holes in the diary there because I was too sick to write or whatever was going on. I was on—here’s how I knew the difference. I was being fed through my veins. And with TPN. It was total parenteral nutrition. That is what they give old people at the end of their life when they’re ready to let them go. Keep them a live a few more days so that they can say goodbye to their friends and family, and that’s essentially what they were doing with me. When the drug came on, and I took it, you can see the progression of the first thing that happened was my diarrhea stopped. And then the second thing that happened was I gained a pound of weight. And when I reached ten pounds, that’s when I wrote in the diary, “It looks like I’m going to live.”

And that’s when you went from 140 pounds to 150.

Right.

At 6’2″.

S: Or 130 to 140. I think I was at 127 at one point. So I went up to maybe 137? I’m not sure. It’s a little fuzzy. Because my mental state was not at peak at that point because my body was so weak. But even then, during that period, that’s when we wrote The Last Session, and I was going out on the stage every night. After unhooking from that IV, which was a 14-hour day process.

So it’s no exaggeration to say that music sustained you.

It’s not—Oh, I can tell you exactly… You might have heard the story but I’ll repeat it.

The year before, 1995, I was just coming out of the hospital from pneumocystis pneumonia. And it was just taking a year before I could walk again, and get up before I could sit up at the piano. And I felt like if there was a gauge my, I built myself up to like 60 or 70% strong, that’s the way I felt. That’s the way I measured it in my own head.

So I sat down at the piano one day, when I could finally sit up, and I just started playing chords. I just started playing music. My favorite big churchy chords, and leaning my head against the wood of the upright piano… and I played all day long. And then I fell asleep, and when I woke up the next day I felt like my energy level had increased to 95%. It was a measurable difference in my energy level by getting on the piano and playing.

And that is when I went, “Oh, this is not a wives’ tale, about music. This is, this is something that is clinical. This actually did something. Because I know what I felt like yesterday. Compared to the way that I feel today.”

And that’s when I started playing songs like crazy and then writing The Last Session, during that period. It was, literally I was writing songs to save my life. And to this day, I write music to keep myself alive.

And that’s when I started playing songs like crazy and then writing The Last Session, during that period. It was, literally I was writing songs to save my life. And to this day, I write music to keep myself alive.

The medications work, but I can tell there is a, sort of a base level of weakness in my body. And if I don’t sustain a really strong diet and exercise and music, I could fall apart really easily. I can see it happen.

Well that might segue into this question. What would you—you know I bet this has actually happened. When you encounter people who are newly diagnosed, what do you have to tell them? Even in the era of PREP etc., what is your advice?

My advice is to take medication, and to take themselves more seriously. And to really, to…. well the first thing is that usually they come to me and they are so emotionally—they hit rock bottom, and they are terrified. And they realize their whole life has changed. And so I try to be as compassionate as I can about their feelings. And then I try to, I just try to encourage them that if they just focus on their health…..

I remember that there was a pamphlet that was given to us at AIDS Project Los Angeles, when I first was diagnosed. And the pamphlet, one of the principles it said is your first goal is to keep yourself alive. Everything else comes after that, but you have to keep yourself alive. So focus yourself on that first. Whatever keeps you alive, whatever you need, whatever you have to do, do that. You know. It may be different for different people; sometimes people just have to make themselves useful.

For a long time I would just go volunteer wherever I could. I would make myself get out of the house. There were some friends of mine who worked in an office, and I said could I come answer the phones in your office. Some other friends of mine, they also had an office and they had a big project where I sat on a couch and I did nothing but put, it was like Rumpelstiltskin. I had a huge room with, there must have been 50 boxes of papers, all out of order. [Laugh.] And my job was to put them in chronological order. And I did that every single day. And sometimes I would go there, put the papers on my lap and fall asleep. [Laugh.] And then get up and go home.

But, I think that’s part of what my, my tell-them is. Make yourself useful. Do what you have to do to stay active. Stay on the meds, and focus on what keeps you alive. If it’s mental, if it’s physical, do whatever you have to do.

And how do you feel about PREP?

Um, I’m probably more for it than I am against it. At first I was horrified at the idea. Because I thought, why would anyone want to take these medications when you don’t have to? But because of my… I’m lucky that get to interact with a lot of young actors, here in New York. Through Manhattan School of Music and also through a church choir that I’m a part of. And I end up coaching a lot of young people; I’m in an acting class. And I started to see what it’s like out there on the single dating scene. I don’t have any of the apps anymore. You know like Grindr and stuff. I’ve given all that stuff up, a long time ago. I used to have accounts just to sort-of keep my nose in the community, or in the so-called “dating” community, if that’s dating? But finally I just, I don’t do that anymore. And I thought, “You know?” There are some of the kids that I know and I think, “You know you ought to be on PREP.” [Laugh!]

[Laugh] Ah! Right.

I…I think sometimes, I would rather be on PREP then to get infected.

Do you ever miss the bars? I mean, I know you are in New York, and in L.A., so maybe you don’t experience it. But in the Midwest and in… Even in New Jersey. Did you know that there are like three gay bars in the entire state of New Jersey?

No.

Um, I know…I’ve seen the dark side of the bars. I’ve definitely seen the dark side of the bars. There is a lot of alcoholism in the community, but I think that drugs are going to be there not matter what…. Do you feel that we are missing something, having moved out of the bars and onto Grindr?

Boy that’s a tough question. I was never much of a bar person. I don’t drink, only because I never much like it. I’ve got no, you now, moral stance of anything against drinking. I just never cared for drinking. Uh, and the camaraderie of the ’70s— I liked being able to seal myself off from the straight world and be in a gay bar, and be in a gay situation—I really enjoyed that. Because it seemed like the outside world was so hostile. But I don’t know that I was ever… Remember that I spent a lot of my time as a musician on the road. So if I went to a gay bar when I was on the road, it was usually to, you know, hang out with some gays or pick somebody up. Or to score pot. [Laugh.] But I can’t say that I was ever much of a bar person to miss it.

But so much of your work probably happened in a bar-type atmosphere, I mean even The Troubadour is kind of a….

Well The Trou…, yeah, that’s a club though. I mean that’s like a performance space. I don’t think of that as a bar as I think of that as a music club.

Gotcha.

I don’t know. It’s very hard—I think if I were younger? Maybe I would… I don’t know. I really don’t know. I suppose the gay bar scene was very useful when we needed to unite people. But Facebook is kind of taking care of that. You know? We didn’t see each other’s faces, and now you can, you know you can get a crowd and go march down 5th Avenue within five minutes by using Facebook. You could do that going bar to bar to bar.

Well I sort of asked that for a personal reasons too, that is sort of the dilemma that I am facing. The bars now are like a ghost town. There is a local bar here in Vegas that I go to, and there’s the drag queen doing her best to keep everybody energized, but how can you do that when the crowd, instead of 20, 30, 50 people you’ve got five. And…

Five? Yeah.

And I just wonder if in losing the bars we are losing a little bit of our….

Culture?

Our culture. I don’t, I don’t know either. I don’t have an answer. I guess it seems that with everything lost something is gained, but I have a hard time now finding what we are gaining, with the demise of all of these spaces.

Jumping track again, how did you meet Jim?

We met on a cruise ship in the Bermuda Triangle.

Oh now that’s awesome.

[Laughs.] I was playing… this was one of my gigs. I was playing a cruise ship, and we were going to Bermuda, and also down to Miami. And he came on as a passenger, and I was playing “One More Kiss,” from Follies one day…. which by the way I had no knowledge of any musical theater. I was basically reading all of these songs out of a book. Because I didn’t know much about musical theatre at time. Or standards. Having been raised in Texas, all I knew was country and gospel and rock. So I would play these songs without the remote understanding of how they were supposed to be sung. [Laugh.]

Oh!

And I ended up singing “One More Kiss” from Follies, which is an operetta song. [Sings a melody.] And I’m singing it like a gospel song. And he thought it was funny, but he was singing along to it, and it is such an obscure song for non-theatre people, and even for theatre people sometimes it can be an obscure song. And I asked him, “How do you know that song?” And he said, “Oh! My God! That’s from Follies.” And that’s when I had to learn about Follies, one of Sondheim’s greatest shows.

And so, um, that’s how we met and he, he was funny, and had an apartment, so I left the ship. [S: Laughs. T: Gasp.] I tell him I only moved in with him because he had an apartment.

Where was he living?

In Midtown, I mean—he lived around 60…around the West side, near the Lincoln Center.

When was this?

This would be 31 one years. 1985.

And… wow. You guys have been together a long time now.

Yeah. Yeah. And, because this pre-dated…Um, I didn’t really have a… We always played safe anyway, because he doesn’t like bodily fluids. He hates it when I say that. It’s true though. Um, so I guess that’s what’s probably his saving grace. And when I finally did take a test, which was 1993, and tested positive, I wasn’t completely surprised. I was pretty wild coming out.

Oh wow. Uh…. what has kept you guys together? That’s a really weird question, but there are so many things pulling people apart, what was your cohesion? What made it “stick”?

[Breathy pause] We laugh at each other. I think it’s the only… Well, our our joke answer is we completely ignore each other. And there is a certain kind of truth to that. We just are both very comfortable being in the same place, being in the same home. And that’s what we like. Uh, he was an only child, and I think he needed a keeper. And I’m very needy, and I need a keeper. So we keep each other. [S: Laughs. T: Ooooh.]

Does he co-write, with your music especially?

No. We’ve co-written a couple of songs. That was kind of very early on, when he had this children’s Christmas musical that he had been doing at some schools, and, it was all using Christmas carols. And so I said, “Well if we replaced all these Christmas carols with original songs, you’d have a real musical.” So we collaborated on a few of those right at the very beginning. He’s very clever. But once I started writing, in my own songs? It’s not really his thing.

What is his thing, by the way? What kind of work does he do?

He’s a playwright, and an actor. He wrote the book to The Last Session. He wrote the characters and the dialog, and then I wrote the song.

Oh, that’s a form of collaboration, absolutely.

Well it is. Absolutely. And The Big Voice: God or Merman, our second musical, was also a collaboration like that. He wrote the script. And created the dialogue, and I wrote the songs. And we write our musicals backward: I write the all this music first, and then he writes the book. Our shows don’t even have a plot until I’ve finished all of the songs, and I don’t even know what the plot’s gonna be. I just write a bunch of songs that have a theme, and then he figures out how to turn them into a show. It’s totally backwards. No one should ever write a show like that. [Laugh.]

[Laugh.] You know, I always tell my students that books are read forward but written backwards. [S: Laughs.] You gotta know where you’re going to get there.

Um, you know I have a lot to go with here, and to start with I could probably start composing what I have so far, and can check in in a week or so for a follow up.

Sure. I think if I want to emphasize anything, it is art. And the creation of art. Not only—I really attribute that to saving my life. That the creation of art, I know, kept me alive for that year, from 1995 up until I started to fail again in 1996, and that’s right when the Crixovan came under test circumstances, and I got into the lottery.

You got into the lottery.

Yeah they had nationwide lottery because they didn’t have enough lab facilities to create enough, and knew that whoever started on it had to stay on it. So they had a nationwide lottery, and I think David France told me that there were only 1,200 slots nation wide. So the fact that I got my named picked, or chosen, or however they did that lottery, was just another one of those little miracles. And when I say the knock on the door with the drug came at the last possible moment—that couldn’t be more true. I probably had two weeks left to live. I was depleted. I was depleted.

And when it came, by the way, when it came I was like, “Oh great, another fucking drug.” Because I tried a lot of things, and I was exhausted by the effort. So it wasn’t like “Oh great, the miracle drug is arrived.” It was like, “Oh another fucking drug. Do I have to be another test case? Alright I’ll take the damn thing.” I was so grumpy and irritable at that time, and I’m glad I did!

This is another thing I won’t necessarily bring into the article, but how do you feel about pot?

I love it.

Do you think…

Pot saved my life. Pot kept me alive. You can say that. I’ve written about it. I’ve talked about it on Facebook and on my (current) blog. Pot saved my life because it gave me an appetite. There was a time there when my digestive system was so broken down that the only thing that I could eat was the BRAT diet: bread, rice, applesauce, and toast. I didn’t write in my diary about smoking pot because it wasn’t legal back then, and I didn’t really want to spread that. But I was… I couldn’t keep anything down unless I could smoke. And I know that that, you know, during that time that music was sustaining me that pot was a major source of health for me. Without it I might not have made it through.

What about in terms of your creativity? Apart from the medicinal aspects, what of the psychological aspects? Do you find has marijuana helped your creativity, does it hinder your creativity? Does the myth of it making you lazy hold up in your own experience?

No, it energizes me and puts me into a whatever alpha waves or delta waves whatever kind of waves have to go through your brain to get you into that thing…

The zone…

It really helps me at my imagination.

I’m glad that you said that because I’ve had my moments. And now I’m so far removed I haven’t had any for months. I miss that creative space. Being a writer, especially, I find that it is harder to focus and concentrate. Right now sitting down in a chair and looking at my computer for an hour or two or three…. I just don’t want to do it, But when I have that…

Exactly! Yes.

I can just sit and and focus and concentrate and I love the way that words… I like the way that my mind pulls ideas and words together. I actually think that it is a gateway to creativity.

Oh absolutely. I completely agree. And maybe I would have arrived at those ideas at some point or other, but for some reason pot gives me a chance to… Like you say, I get into intense focus when I can go for hours. And the ideas are multiplicitous. The ideas come like crazy. And also they come through… Unusual connections are made. That I would never have thought of.

I agree. I wonder: Are you working on any projects now? Any big projects?

Well here’s the thing. As I said before, I don’t really know what my project is until I’ve finished. And I go one song at a time. And once again I think it goes back to this: rather than try to write something big, I try to write something small. For instance, the last big piece that I wrote…well there were two. One was a mass. The mass I composed, I knew I was writing a mass. On the other hand, half the songs in that mass didn’t need to go in the mass. They were just written as a matter of course. But New World Waking, which was my big off-Broadway concert piece, which deals with John Lennon and violence in the world, all of those songs came piecemeal and I didn’t know what I was writing until I got to the end of it. And then I went, “Oh! This is a concert.” And it debuted at the Davies Symphony Hall, for the Gay Men’s Chorus in San Francisco.

And you are coming up on the 20th anniversary of that?

No; the 20th anniversary was The Last Session. The Last Session was our first musical. That’s the one with all my songs about AIDS. Those were the songs that saved my life. And we just met with the producer, so we don’t have a venue or a date or anything like that, it may not even come off. I think it will. But that was our first show. And that’s what we are coming up on the anniversary of the off-Broadway production of The Last Session.

Maybe this article will help. That will certainly help bring some national attention.

That would be great. That’d be great. I’d love that. We were sort of drowned out, in New York we were sort of drowned out by RENT, which was happening at the same time. And uh, RENT had a much bigger budget and was a different kind of a piece than ours was. And it was also New York-based, and everybody kind of knew it. So we were over on the side. But people who loved RENT also loved The Last Session. And if they stood in line to get into RENT and couldn’t, they’d race over to our theater to see our show.

Um….[Shakespeare discussion]

I’ve been reading a lot of Shakespeare lately. I have an acting class that I go to on Sundays, and I have been obsessing over Richard II and The Tempest. Over Prospero.

Shakespeare is amazing.

Well it sort of started because I was in an acting class. I had never been in one before, and my friend made me come. And I thought, “Well, if I’m going to be in acting class then I should read some Shakespeare.” So I just started reading to make myself literate. And I started learning these monologues.

And when I got to Richard II, I really really… who was finally put in jail, and he had to die in jail. But all of his speeches—I started to relate to them as a person with AIDS. This hooks up with arts and understanding, but I started to see his speeches about death and mortality very much in my own terms of living with AIDS. And two very potent speeches… One was the… “Let us talk about the death of kings, sit on the ground and talk about the death of kings” is one of the speeches. And the other is one toward the end where he is in jail, and he’s just pondering that he is going to sit there and die. And how he makes his thoughts turn into people and tries to people his little jail cell with thoughts. And just keep things going on and on. And I just, I can’t get enough. I can’t get enough.

And now Prospero, I’m starting to realize how Prospero–because Tempest was Shakespeare’s last play. And it’s basically his goodby to the stage. He’s basically saying, you know, “If you keep me on this bare island, or bare stage, you know—release me. Give me a hand of applause so I can take a bow and get the fuck out of here.” And I think this relates to AIDS too because when I went into that period in 1996, just before the meds came in… No. It was the end of 1995, when I was writing The Last Session songs. And I came so close to death, I started to not be afraid of it anymore. Because it felt like, “Oh, this is nothing. You go to sleep.” And…and this is sort of what Prospero says to Ferdinand, when he says, you know, “All of this will dissolve. The great globe itself—It will all dissolve. And leave not a rack behind.” And, “We are such stuff as dreams are made on, and our little lives are rounded with a sleep.” It’s such a—the thing I love about it is very unromantic. It’s just very matter-of-fact. All of this stuff you see? It’s all going to go away. And we’re just going to go to sleep. And I thought, “There’s something kind of comforting about that.” We get so caught up in the stresses of the world which is injurious to our health.

One thing I have learned, about living with AIDS, is there are a lot of causes that people could take up. And I just don’t let myself get caught up in every single cause. I figure out what I can handle, and then I handle that.

Hmmm. Well of course you are helping me see echoes between Prospero and Hamlet that I’d never seen before.

Right. Shakespeare was the first writer, especially English, to ponder these feelings. To ponder life rather than just throw a narrative up. And self doubt, self guessing, and wondering about the mystery of life and all that stuff. That’s what he introduced. That’s why his plays are so powerful.

[Wrapping up…] I’ve got a lot to think about and a lot to write about; this is going to be a fun article.

Arts and understanding, so anytime we can wrap up all the arts in there, I really believe that the arts saved my life. That’s, that’s the theme of my life.

Well I don’t know if I am going to be able to say anything fresh and new in this article, but at least I will be able to say things in my own voice, and I guess that in itself will make it fresh.

It will make it fresh. And look, you know—the thing about it is, a person like me—I haven’t thought much in the way of fame. People can strive for fame in very specific ways. And I’m just trying to stay small. My life is very small right now. I have my bedroom, I do my stairs, I play on my guitar, and I try to keep everything very contained. And you know, it’s nice when people can look at my work and say, “You know there is really something here for people to learn from.” But I, you know I don’t have a PR agent or try to reach out. So I think any time someone writes about this from perspective, which you will certainly bring to it, I think people will be seeing it for the first time.

Do you ever miss L.A.?

No. I love New York. I wouldn’t trade it for a million bucks.

Wow. That’s cool. I don’t get it…

I hate driving in a car.

Oh yeah, that I totally get.

I mean I hate driving. I’ve always hated driving. I’ve been in two car wrecks driving. Both of them were my fault, because I hate is so much. And when we went back to visit, all I could think about was, “How many hours am I sitting in this fucking car when I could be on a bus reading? or a subway reading?”

I totally get that.

You know my mind is always engaged. It’s always engaged in something. But when I’m driving in a car, I’m stuck.

Yeah. For me, nothing ruins a good mood faster than L.A. traffic.

Now some people find it a good meditation. And I mean God bless ’em, but not me.

Have you seen the movie La La Land?

Yes.

Did you like it? How did you feel?

Well let’s see. It’s a musical about jazz in a land with no musicals and no jazz. [Laughs.] I thought it was sort of dull. It was charming.

It was charming.

It kind of won me over at the end when they did this sort-of dance representation of everything that had happened in the movie. And I thought, “That’s kind of clever. That’s kind of cute.” And I went away thinking it was a nice film. But boy: they can’t sing! There is no singing in this thing. And so, it’s hard, she’s like this… “I’m a person who can’t sing, so it’s all breathy.” There is no voice there. That drove me crazy, a little bit. But it was cute. It was sweet.

I agree. I agree. I’m surprised it’s getting all the awards it’s getting. It was good… but…. oh well.

I’m thinking it must have hit—sometimes a movie hits when people are emotionally needing that at the moment, and maybe people in L.A. needed that at that moment.

Got it. Yeah, that makes a lot of sense to me. Oh! What has Trump done to you emotionally, and in the sense of your own creativity? Has it changed? Does it make you angry? Do you want to fight back….?

[Laugh.] I kept thinking, before the election…This is terrible. Selfishly, I kept thinking, “If he wins, then we can finally start writing some music about something.” [Laughs.]

Ah! Funny.

’Cause, when, you know? When everything is going our way in the government, there is nothing to rail against. If you don’t have anything to rail against, you’ve got nothing to write.

Isn’t that funny! I was thinking the exact same thing.

And I thought, okay now, now we can finally get… You know also, and this is…this is just really my political side. I think we, liberals and everybody, got so complacent about the government is going to do everything for us because now the government is on our side. And the picking, the nit-picking of liberals drives me out of my fucking mind. L-G-B-T-Q-R-S-T… I mean, there are so many divisions and subdivisions and subdivisions of all the people we have to keep track of and we have to be politically correct about—it gets to be too fucking much!

Yeah.

You know? And, and there were…. No, we’re not going to buy food from that place, we’re not going to that place—everything is a fucking boycott because someone said something wrong, and I thought, “You know this is just as bad as living under Republicans!” It’s like this weird, inward-turning self censorship. For instance, I was in this debate today, on the Internet. And they were all, “Yeah, we showed ‘em at Berkeley, Man. We’re not going to let that guy talk.” And I thought, you just gave Trump his biggest victory. And you’ve got Yiannapolis on all the major news networks—you gave them everything they wanted. And still… The people I knew who were in the peace movement, because I studied the peace movement and did a march on Lynchburg, and studied Dr. King’s philosophies in a serious way. And they are all defending this violence! And I thought, “Why are you defending violence?” “Oh, well he said violent things.” No it’s not the same thing. It’s NOT the same thing. When you defend violence, you’re just… You know everybody’s become so tribal now. And so now if our side does it, well, “We’re on our side.” And I’m like—no. No. You are so ignorant, you have no idea, you did not study what Dr. King was about. You parade his name about but you know nothing about his speeches. And that sort of annoys me. We are our own worst enemies.

So how does that affect your art?

Well, I’m starting to write protest songs. I’m starting to write protest songs. Just like a 60s—I said the other day that I’m turning into the Baptist Bob Dylan.

Oh funny.

Especially ‘cause now that I have a guitar, now that I’m almost good, now that I’m competent on guitar. I’m starting to write all guitar songs, and I just wrote last week the song that I posted online, on my Facebook page, this song called “Now That We Know.” And it’s directly from… One time Bob Dylan, you know Bob Dylan wrote this song, “Blowin’ in the wind.” The answer my friend is blowin’ in the wind?

Um hmmm….

Well he said he wrote that in response to a Woody Guthrie song, “Where have all the flowers gone.” “ The answer my friend is blowin’ in the wind,” that’s how he wrote that song. And Leonard Cohen, when Leonard Cohen died and they kept playing his big song, which was “Everybody Knows,” and I thought okay… what would be the next song? Alright…now that we know…

Oh….

Where do we go? So this is a consequence of my Monday night songwriter group because they’re a bunch of folkies. And the generation of this group goes back to the ’70s, or actually the ’60s. And some of them are contemporaries of Bob Dylan and they, they write this, um, these protesty kind of songs, so I’m starting to pick that vibe up. [Laughs.]

So in a way maybe… Did you find yourself kind of falling into the liberal complacency under Obama? Are you finding your own sense of creativity now is being invigorated through all of this?

Sure! You know, we don’t… Creativity really only happens under pressure. Just like a deadline will make your… Leonard Bernstein had the famous quote: “If you want to make a great work of art, you need a plan and not enough time.” But I also think you also need something to rail against, you need something to write about. And righteous anger is a lovely thing to write… It’s a self-motivating thing.

You know the songs from Last Session I wrote because I was under extreme duress from needing just to live. So that was my motivation for writing Last Session. I needed, I needed to write this music to live. So I had to dig deep, and excavate all of those emotions. And I think now we, we see a world that feels like it’s on the brink of chaos, not realizing the world is always on the brink of chaos [T: Um hmmm.] But…. yeah. Having something to fight against gives you a motivation because now, now your vision becomes more clear.

So you win by losing and then you lose by winning. [S: Laughs]. Politically speaking I guess.

Yeah.

My friend Mark Thompson, recently deceased, told me once that the greatest truths are often paradoxical. So …

Absolutely. Oh I love that. Yeah.

He validated that… I had already seen it, but he stated it far more eloquently and simply than I would have.

If you’re comfortable, then what’s the point?

Yeah. Well my friend thank you so much….

S: My pleasure, Todd!

So I’m gonna take my dog on a long walk and digest this conversation and uh, I’m looking forward to writing this article.

I’m really honored that you thought of me.

Well like I said, I almost didn’t even propose it because I thought they would have covered you from all different angles by now, and I was kind of surprised when they said, “Who’s that?” And I was like, “What!”

How easy they forget, one of their cover boys. I’ll send you a picture of the cover. Jim and I were on the cover.

I would love that. I’m hoping that you’ll be on the cover again. Oh and that was another… I like to make sure before I do it, they’ve asked for your contact information in order to set up a photo shoot…

Sure yeah.

So can I give them your phone number?

Absolutely, yeah.

Cool!

E-mail, phone, whatever. Both.

Both. I’ll do both.

Ok.

Alright! Well thank you so much Steve, and I’ll talk to you again very soon!

Love you man!

Love you too.

Bye!

Bye bye.

[click]

That was cool.

[01:15:24]

©2017 by C. Todd White and The Tangent Group.

All rights reserved.