Robert Duncan in San Francisco

Robert Duncan in San Francisco

by Michael Rumaker

Published by City Lights/Grey Fox

Published January 15, 2013

History (biography)

143 pgs. • Find on Amazon.com • WorldCat

Reviewed by Stephen O. Murray

January 2, 2016.

Though I have read Michael Rumaker’s overwritten (lyrical) A Day and a Night at the [Everard] Baths (1979) and was aware of My First Satyrnalia (1981), I’ve never considered Rumaker a writer, let alone an important gay prose writer.

The copy of his Robert Duncan in San Francisco (written in 1976–77 about a 16-month stint in the City by the Bay two decades earlier) that I bought online has a title page defaced by an attack, headlined by “This book is AWEFUL” followed by changing the title to “Michael Rumaker in San Francisco,” continuing: “for only 16 months used Robert Duncan [1919–88] as an excuse to write about himself and his not interesting life. As a writer he is marginally acceptable. City Lights Books [publisher of an edition supplements by a 2012 interview and some correspondence almost all of it from Rumaker to Duncan] is really groveling for material. It is BAD, BAD, BAD Duncan was also a dull, bore I’ve met him several times hard to look at—one eye off center” (punctuation and its lack from the original).

Surprisingly, this earlier owner went on to underline many sentences and to include a number of stars in the margin for points without challenging any of them.

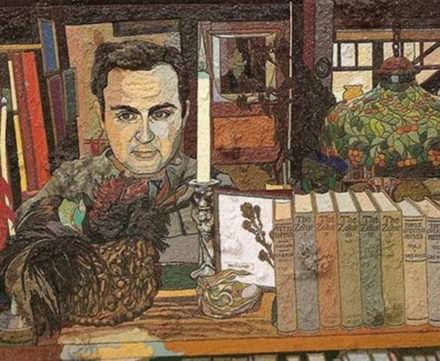

The 22-year-old Rumaker (born in 1932) blocked the 34-year-old Duncan’s sexual advances not from loyalty to Jess (né Burgess Collins, 1923–2004) the painter who was Duncan’s life partner, but because Rumaker was not attracted to Duncan. (He found the pictures of a younger Duncan attractive and felt sorry for the loss of youth/beauty Duncan had had). Rumaker admired Duncan’s poetry and his courage in coming out in print in 1944 in Politics.[1]March 1944, “The Homosexual in Society,” pp. 209–211

From Rumaker’s memories, Duncan seems to have like Rumaker’s writings—at least before the memoir, after which Duncan never again communicated with him.

Jack Spicer was nasty to Rumaker. Rumaker believes that part of this was Spicer’s alcoholism, but also fury that Rumaker was f*cking (obscure poet) Ebbe Borregaard, whom Spicer wanted and couldn’t get.

Rumaker celebrates Duncan as a role model of self-acceptance and of making a home with a lover (a mere two blocks above where I live, at 1137 De Haro), albeit not monogamous. Rumaker himself was petrified by fear of the San Francisco Police. Rumaker makes a point of Duncan’s slight frustration that Charles Olson (Rumaker’s Black Mountain mentor, 1910–70) seemed more interested in men who had, like himself, been raised Catholic, including Rumaker than in non-Catholics however ex-. I find it a bit odd that Rumaker does not mention how Irish (Catholic) the San Francisco police force of the 1950s (and later) was.

1137 De Haro, built in 1900, is the middle units of a vertical triplex, on Potrero Hill in southeastern San Francisco

The most vivid and, I think, valuable part of the memoir of San Francisco of the mid-1950s is Rumaker’s account of being picked up along with two dozen other men while he was walking home from hearing Miles Davis, going up Polk Street. He was charged with “vagrancy” in a doorway with another man. Alone of the 24 or 25 guilt-ridden and frightened arrestees, Rumaker pled “not guilty.” The case was dismissed by Clayton W. Horn, the same judge who presided over the 1956 obscenity trial of City Lights Books for publishing Allen Ginsberg’s HOWL (which Rumaker criticized in the Black Mountain Review, after R’s alma mater, Black Mountain College had folded).

Rumaker was able to go back to work, and his name was not published in the daily papers as was the norm for those pleading no contest or guilty of vagrancy (which could be applied to anyone not carrying a thousand dollars—a thousand 1956 dollars!), loitering, public indecency (a legal category with elastic boundaries).

The documentation of what was too well-founded to count as “paranoia,” and of the mindset of “being not quite permissible affected our own feelings for each other,” with no feelings of solidarity or any positive identity, is more important than any insights into Robert Duncan’s character or persona or importance on the San Francisco poetry scene.

The Morals Squad was everywhere and the entrapment of gay males in the streets, the parks and inn numerous public places was a constant fear and a common occurrence.

The police abuse of surveillance and harassment of suspected homosexuals was only curtailed after various clergymen got a taste of the police modus operandi around Calfornia Hall (also on Polk Street) at a 1964 New Year’s Eve Ball. As Deborah Wolf wrote,

The police pursued a policy of deliberate harassment by taking photographs of each person entering California Hall, by parking a paddy wagon and several police cars outside the entrance to the building, and by entering the hall themselves. During the evening three attorneys and a [straight] woman council-member were arrested for “obstructing an officer in the course of his duties” as they argued with the police at the entry to the hall…. The outrage felt by heterosexuals who had attended the ball, including clergymen and their wives, at this show of harassment led to a politicalization and a strengthening of their commitment to fight for the rights of the homophile community, once they themselves had experienced similar repressive actions at first hand. (Lesbian Community, 1979:55)

© 02 January 2016, Stephen O. Murray