Richard Bruce Nugent

Essay by Stephen O. Murray

February 26, 2009.

Partly due to surviving with an intact memory of the “New Negro” era, Richard Bruce Nugent (1906–1987) emerged from total obscurity as an insider source on the core group of the Harlem Renaissance for historians David Levering Lewis (When Harlem Was In Vogue, 1981) and Arnold Rampersad (biographer of Langston Hughes) and as a heroic openly gay artist (his Firbankian “Smoke, Jade, and Lilies” was reprinted in the anthology Black Men/White Men in 1983). Nugent was the major character in both the past and present parts of the 2004 film Brother to Brother directed by Rodney Evans.

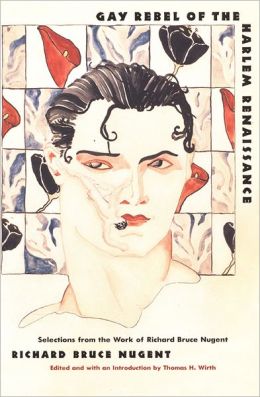

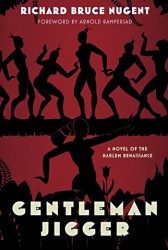

Nugent published practically nothing during his lifetime, but Thomas H. Wirth put together an anthology of Nugent’s writings with a considerable biographical essay and some of Nugent’s drawings as Gay Rebel of the Harlem Renaissance in 2002. Wirth included excerpts from Nugent’s unfinished novel, Gentleman Jigger, and went on to edit for publication the whole novel, which was published last year

Nugent published practically nothing during his lifetime, but Thomas H. Wirth put together an anthology of Nugent’s writings with a considerable biographical essay and some of Nugent’s drawings as Gay Rebel of the Harlem Renaissance in 2002. Wirth included excerpts from Nugent’s unfinished novel, Gentleman Jigger, and went on to edit for publication the whole novel, which was published last year

(“Jigger” was a term for a mixed-blood/creole, no more polite than the term with which it rhymes.)

There are two nearly completely distinct parts of Jigger. In the first, the light-skinned scion of the Negro elite, Stuartt (Nugent) moves from Washington, D.C. with his friend (a poet based on Langston Hughes) to Harlem.

There, Stuartt overcomes his disdain for those with very black skins when he meets Rusty, the intellectual and organization leader of the “New Negroes” (Wallace Thurman). Soon they are sharing a bed (literally: they had sex with other men, not with each other) in the infamous “Niggerati Manor,” putting out what in real life was the single issue of Fire!! (with Nugent’s “Smoke”) and preening as superior to the “Talented Tenth” (while refusing to write about professional, middle-class Negro success as W. E. B. DuBois wanted Negro writers to do). The big set piece is the same rent party that Thurman made the centerpiece of Infants of the Spring (which of them wrote his account first is unresolvable; Thurman’s roman à clef was published in 1932, however).

There is no transition explaining how/why Stuartt migrated downtown to Greenwich Village. In the second half of the book, he toys with (and is a boytoy for) Italian emigrant gangsters and taken up in turn by men higher and higher in the Mafia, ultimately one based on “Lucky Luciano” called Orini. In this half, Stuartt is passing as white without any particular effort. His musical performance career is blossoming when Stuartt casually mentions that he is not white. Frustratingly, Nugent’s novel does not go into how Orini reacted to the news that his boytoy was a _igger.

There is no transition explaining how/why Stuartt migrated downtown to Greenwich Village. In the second half of the book, he toys with (and is a boytoy for) Italian emigrant gangsters and taken up in turn by men higher and higher in the Mafia, ultimately one based on “Lucky Luciano” called Orini. In this half, Stuartt is passing as white without any particular effort. His musical performance career is blossoming when Stuartt casually mentions that he is not white. Frustratingly, Nugent’s novel does not go into how Orini reacted to the news that his boytoy was a _igger.

(I doubt that whether the initial consonant was “j” or “n” would have much mattered to him, as it did not to those involved in Stuartt’s stage career.)

Also, it seems difficult to credit that the worldly, seemingly sexually experience Stuartt does not know what to do when he takes Rey (Reynaldo), a young Italian study to his apartment. (Stuartt knows how to give pleasure by the time the “Avocado King of New York,” Frank, takes him up and is a male courtesan by the time Orini takes him away from Frank, but Nugent does not provide any graphic details of Stuartt’s sex magic techniques.)

As a contribution to understanding how gangsters and “fairies” related to each other, the second part may have some historical validity and interest but not to understanding interwar black/Italian relations, since none of the three Italian gangsters knows Stuartt is Negro.

As a contribution to understanding how gangsters and “fairies” related to each other, the second part may have some historical validity and interest but not to understanding interwar black/Italian relations, since none of the three Italian gangsters knows Stuartt is Negro.

Both parts have a light touch, amused by the pretensions of all the characters, including the autobiographical one of the young Richard Bruce Nugent as Stuartt.

For wider context see Steven Watson’s The Harlem Renaissance and Christa Schwarz’s Gay Voices of the Harlem Renaissance. Nugent plays a major role in the movie “Brother to Brother.”

© 2009, 2016, Stephen O. Murray

This was originally posted on epinions 26 February 2009