May 12, 2001

Lawrence R. Schehr writes aptly of Renaud Camus’ Tricks:

[Camus’s] stories of sexual escapades are told as if there were nothing, but absolutely nothing, wrong with sex, and a fortiori with homosexual sex. There is no apology, nor is there any titillation. These are simple stories simply told…. This book is a series of narrated incidents unframed by the generic constraints of the confessional genre…. Missing are the posturing of John Rechy’s Numbers, the narcissism of pornography in general, the politics of betrayal of Jean Genet, and the confessional, apologetic, or explanatory modes of Proust and Gide. Never disguising its own comfortable amorality, Tricks is a text pleased with itself. (The Shock of Men, 129–30)

Not, I think, smug or unsearching about those Camus encountered. And, although not insouciant, it seems that the possibility that anyone would consider his sexual encounters immoral never occurs to the narrator (though I suspect this is deliberate and that the author himself has at least heard of such views!)

Not, I think, smug or unsearching about those Camus encountered. And, although not insouciant, it seems that the possibility that anyone would consider his sexual encounters immoral never occurs to the narrator (though I suspect this is deliberate and that the author himself has at least heard of such views!)

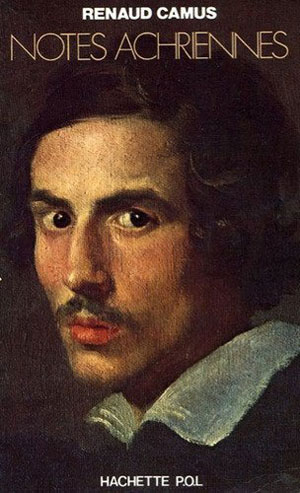

For Camus, Genet’s representations of homosexuality “too much resemble the one imagined and depicted by his worst enemies” (Notes Achriennes, 1982, 132, quoted, p. 139). For him, Genet is the worst example of the homosexual eagerly accepting being defined by the discourses of hostile others. “Homosexuality has nothing to do with Evil. It is not a provocation…. Quite simply, it just is. It is on the side of pleasure, joy, amusement, affection, and—if we must, we must—love” (NA 132, qu. 145).

And from M. Camus himself:

Sometimes I think that I am the only queer who likes queers, and for whom heterosexuality as such, even that of an eventual lover, is completely without prestige. A more or less liberal, adventuresome, frustrated or drunk heterosexual who would “allow” me to do this or that to him means nothing to me. I have no desire to be “accorded” anything, as in old-fashioned heterosexuality. (Chroniques Achriennes, p. 12; translated by Schehr, who surely projected “queer” onto Camus)

I wish that someone would translate his Journal Romain, “an updated gay version of Mme de Staël’s Corinne and “a very personal and subjective record of a gay consciousness trying to write in and about Rome” (153), and working through Stendhal’s Promenades dans Rome. The first third of it was columns for Gai Pied. Its editors lost interest, however, or were uncomfortable with the negative portrayal of Italian men deigning to have sex with men.

“For Camus, the Italian homosexual seems somehow stuck in a role that comes straight out of nineteenth-century novels, Balzac’s in particular” (169). The Romans he encounters ‘are all terribly genito-anal: jerking off, blow jobs, fingers up the ass, and attempts to butt-fuck, beyond that they are neither very knowledgeable nor curious” (JR 263) (166)—another instance in which Camus’s frustrations about Romans are similar to American gay men’s frustration with the French and Latinos, both old world and new!

And, “Italians endlessly ask me in sexual situations why I smile, which seems to concern them greatly. For them, making love is something completely serious—for me too, but in the same way—and even a bit ‘dramatic,’ where any humor is only our of place” (JR 277) (167).

Instead of the free sexual “play” that Camus expected, the Monte Caprino is

filled with one-way actions, taboos, and ritualistic reaffirmations of heterocratic sexuality. Italian men who go there for gay sex seem, as often as not, not to want to be gay and not to want to know who they might be… [eager to deny] that their own present behavior is not just a one-time chance occurrence [as in Foucault’ denial of self-awareness before the late-19th century in northern Europe]. What these men affirm to Camus is a discontinuity of behavior, or thought, and of semiotics. They have affirmed only one thing, the internalized figure of the self proffered by the other, the picture of the ‘faggot,’ ‘pédé,”‘ ‘frocio.’… The free sex of the Monte Caprino comes wrapped in garb of self-loathing. [JR, 159]… Gay Roman men behave as if they were macho heterosexual men who were not gay but who would deign to allow themselves to be serviced. Alternately, these Roman men seem to be playing at their antithesis: coquettish female virgins who have to be wooed. For Camus, coming from a Paris of reasonably open gay relations, the alienation of the Roman homosexual is too much to bear. [161] There is a parasitic system of one-way streets, power differentials, and systematized abuses, like those of The Barber of Seville—except in this live production, all the gay men of Rome play Rosia (JR 65)….The ideal of the Italian homosexual or at least the Roman homosexual is to be invisible (JR 146)…. It is not that Camus is looking for some fixed, doxological meaning. It is rather that he is seeking in vain what I would call ‘meaningfulness,’ which I would define as the possibility of meaning(s), the potential for sense, and the plurality of possibilities” (162). I use language to combat the devaluing of a sexual that turns the meaningfulness of sexuality into a theatricalized version of male and female signs, with no free play or foreplay, whatsoever” (JR 163).

published on epinions, 12 May 2001

©2001, 2016, Stephen O. Murray