Some Remarkable Men: Further Memoirs

Some Remarkable Men: Further Memoirs

by James Lord

Published by Farrar, Straus and Giroux

Published September 30, 1996

History (memoir/biography)

360 pgs. • Find on Amazon.com

Reviewed by Stephen O. Murray

August 23, 2000

James Lord [1922—2009] was something of a golden boy in the years following World War II when he was cultivating remarkable men and exceptional women. Sculptor Albert Giacometti, the one Lord most admired (and on whose biography his spent fifteen years), thought that Lord looked “thuggish.” I don’t see this in Giacometti’s portrait of Lord or the photographs from the period that are included in the book. Having read Some Remarkable Men, Six Exceptional Women, The Giacometti Portrait (but not the Giacometti biography—yet), and the more recent (2010) My Queer War, I’d say that Lord has formidable skills for appreciating various kinds of greatness and for diagnosing self-delusions. Although his sympathy for human weakness is considerable, he can wield scalpel judgments with a surgeon’s skill.

What we might now call his “access” to some figures who were famous in their day and are now legendary was considerable. He records the chutzpah his younger self exhibited, but it must have been accompanied by great charm. In a very long-term sense, he earned what he took as a youth with the prose portraits he wrote in his 70s (based on his earlier journals).

The first one in Some Remarkable Men, and the one I find least satisfying and memorable, is of Harold Acton (1905—1994), notorious as an Oxford lover of Evelyn Waugh, who later based the character of Anthony Blanche in Brideshead Revisited partly on him. Of Acton’s own Memoirs of an Aesthete, in Lord’s view “toys with the truth, trifles with candor, dwells upon all that is prestigious and sublime, leaving accuracy to drift in the doldrums of wistful speculation. Wistful because Harold could have been an author of noble attainment if he had had the fortitude to look the truth in the face and quite candidly account for what he saw.” Instead, he wrote some specialist history of Naples and mostly focused on maintaining the Florentine villa he inherited.

The Acton chapter is titled “The Cost of the Villa.” The one on the snobbish self-styled baron, the once shocking painter Balthus, could easily have been title “The Cost of a Chateau.” The artist’s pretensions of nobility required a chateau that he could barely afford to buy but could not afford to furnish. A large rug Lord has inherited plays a prominent part in the Balthus chapter. Lord judges that Balthus lost his artistic gift during a long time he spent furnishing his chateau instead of painting.

Lord’s indictment of Balthus [Balthasar Klossowski de Rola, 1908–2001] seems overly harsh to me, and I think that he is definitely too dismissive of the body of work (prose, poetry, cinema, theater, drawing) of Jean Cocteau. Cocteau was guilty of more than a little cravenness in his need to be admired. Lord harbors resentment at how he was used in Cocteau’s jockeying for approval from Picasso. (Lord was the confidant of Picasso’s discarded model/muse/mistress Dora Maar, and his ambivalent mixture of admiration for Picasso’s art and contempt for him as a human being is even more central to Dora and Picasso).

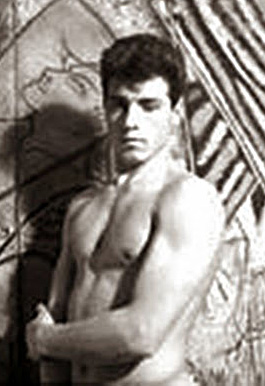

Lord is far more sympathetic to Jean Cocteau’s last lover, “Doudou,” (Edouard Dermit, pictured here in 1948), than Frederick Brown was in his biography of Cocteau (1889—1963), and one can sympathize with Lord’s impatience with Cocteau’s politics. (I’m convinced that the only politics about which Cocteau had the slightest interest were personal and the politics of artistic factions. He verged on chumminess with the Nazi occupiers of Paris and supported Picasso’s defense of the Soviet invasion of Hungary.)

Lord is far more sympathetic to Jean Cocteau’s last lover, “Doudou,” (Edouard Dermit, pictured here in 1948), than Frederick Brown was in his biography of Cocteau (1889—1963), and one can sympathize with Lord’s impatience with Cocteau’s politics. (I’m convinced that the only politics about which Cocteau had the slightest interest were personal and the politics of artistic factions. He verged on chumminess with the Nazi occupiers of Paris and supported Picasso’s defense of the Soviet invasion of Hungary.)

There is much insight about the subjects of the first three chapters, and I have slighted their often biting humor, though I thoroughly savored it.

Lord feels that Acton, Balthus, and Cocteau failed to live up to their talents (genius even in the latter two instances) from various kinds of dishonesty, pretension, and greed. The finale, nearly half the book is e long memoir of Lord’s relationships with the Giacometti brothers, and Alberto’s terminally unreasonable wife Annette The portrait of the impossible wife is particularly vivid, and, considering the legal havoc she wreaked for Lord, admirable in sympathy for someone he says—and conclusively demonstrates—“didn’t know how to listen.”

Lord’s love and admiration for all three brothers is not only expressed but explained credibly. Diego is the most readily likable. Alberto comes across as a martyr to his vision of perfection and a saint in his total commitment to truth and unconcern about whether anyone else found truth to be beautiful or marketable.

Alberto Giacometti (1901–66) told Lord that “writers are supposed to write, and, if they are serious about it, they write down everything that seems important, plus a good deal that isn’t.” Perhaps Lord recorded that good deal more in his journals, but he has refined it in the books of his old age.

Lord writes very, very well and has an unerring ability to select the details that reveal a character. That he both knew and can write insightfully about many legendary artists in postwar France gives the book substance of great interest along with a very polished style, in this volume as in its predecessors, including his fascinating account of sitting for a portrait by Giacometti in which every session seemed to end in the artist destroying what he had done. Although being interested in those he has written about is a good motivation for reading Lord, his abilities to tell stories and reveal characters is a better one.

P.S.—On the lesbian couple Lord wrote about in Six Exceptional Women:

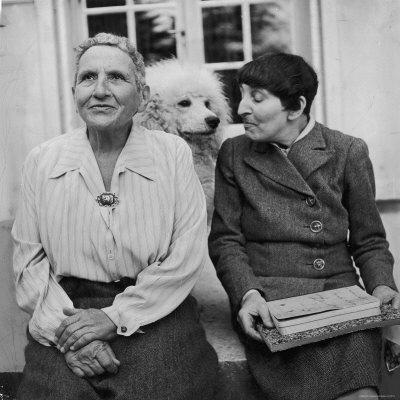

I checked out James Lord’s Six Exceptional Women to read the chapter on Gertrude Stein (1907–46) and Alice B. Toklas (1877–1967), and the one on Arletty, and these are the two that I read first. I have read a number of memoirs of Stein-Toklas by young American males who found favor at least for a time with Stein (Hemingway being the most famous, Sam Steward probably the most intimate). Although Lord did not know Stein well or very long, he provides a very incisive memoir of her arrogant obliviousness (to others, and, he suggest, to paintings, though she famously bought and commissioned work from Matisse and Picasso before they were famous and had a part in making them famous).

I checked out James Lord’s Six Exceptional Women to read the chapter on Gertrude Stein (1907–46) and Alice B. Toklas (1877–1967), and the one on Arletty, and these are the two that I read first. I have read a number of memoirs of Stein-Toklas by young American males who found favor at least for a time with Stein (Hemingway being the most famous, Sam Steward probably the most intimate). Although Lord did not know Stein well or very long, he provides a very incisive memoir of her arrogant obliviousness (to others, and, he suggest, to paintings, though she famously bought and commissioned work from Matisse and Picasso before they were famous and had a part in making them famous).

Although he regrets telling her off during their last meeting after she made a particularly stupid and smug pronouncement, Lord had new reason to be irritated at Stein after her death. The theme of the remaining part of the chapter is that Stein should have provided more explicitly and clearly for Toklas in her will. It chronicles an increasingly poor and pathetic widow bravely and uncomplainingly surviving the insensitive and monumentally greedy Stein heirs.

(This is certainly a cautionary tale for same-sex partners!)

reviews of both books were published on epinions, 23 August 2000

©2000, 2016, Stephen O. Murray