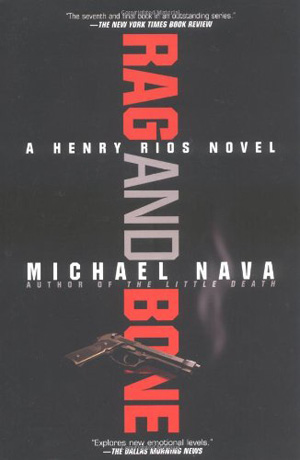

Rag and Bone

Rag and Bone

by Michael Nava

Published by Putnam Adult

Published March 19, 2001

Fiction (mystery)

304 pgs. • Find on Amazon.com

Reviewed by Stephen O. Murray

May 4, 2001

I do not consider myself being anything of a connoisseur of murder mysteries, though I usually guess “whodunit?” correctly before being told.

The gay Chicano lawyer/writer Michael Nava is tired of writing mysteries, and states in the acknowledgments to Rag and Bone that this will be the last in the series.* (It’s the seventh.) The jacket calls it “a Henry Rios novel” rather than “a Henry Rios mystery,” as earlier books such as How Town and The Death of Friends were labeled.

Raymond Chandler, the founder of hard-boiled LA murder mysteries, famously complained, “The better you write a mystery, the more clearly you demonstrate that the mystery is really not worth writing.” Although Nava has lost interest in churning out mystery novels, after having produced seven in sixteen years while practicing law all but one of those years, he is good at it. He is definitely quitting while he is ahead of the game. I am a fan of the character and have mostly tolerated rather than welcomed the genre demands of Henry Rios figuring out who really killed whomever. (That only a few corpses pile up is also a relief, especially since the “classic” mystery novel I most recently read was Dashiell Hammett’s The Dain Curse.)

Weary both of his mostly guilty clients and the “system” of justice in Los Angeles, having lost his lover to AIDS a few volumes back, and been on the wagon for many more, the 49-year-old Henry is very tired at the start of the novel. “Half dead, readier to go the rest of the way than step back into the world,” he tells his sister from whom he has long been estranged, but whose name he called when he had a heart attack while arguing a case in appeals court.

I wasn’t suicidal at all, but I was finding it hard to come up with reasons to be alive. I didn’t feel needed.

Your friends need you. So do your clients.

My friends love me, they don’t need me. As for my clients, well, lawyers are fungible. There is no one to whom I am irreplaceable. They’ve all died.

There is a mystery, the solution to which I guess wrongly two-thirds of the way through the book. As usual in the mysteries written by Nava (and, before him, Joseph Hansen), there are very complicated sexual identity politics involved. There are also ethnic identity politics in Henry’s personal and professional life. However, the primary concern is with family.

Over the course of Rag & Bone (the title derives from Yeats’ “The Circus Animals’ Desertion”), Henry reacquires a relationship with his lesbian, former-nun, college-profession sister Elena (who has an offstage lover). He learns that she gave birth to a girl whom she gave up for adoption immediately following birth 30 years earlier he didn’t know about. This seemingly battered woman, Vicky, enters the lives of her birth-mother and uncle-by blood with a son who is eleven going on fifty and looks strikingly like Henry did when he was eleven.

Elena wants to integrate Vicky into her life, Henry dotes on his grand-nephew. All of them need his professional expertise, which is adequate to their complicated needs (whether or not lawyers are interchangeable).

Acquiring a family rather than producing one is the fulfillment of some gay men’s wishes. Henry gets even more than a smart and not-totally-traumatized surrogate son: he also gets a role model co-parent, lover, and masculine role model, “Johnny” (who was surely christened as “Juan”). I don’t know what the Latino term for politically correct in-group coupling is (it’s “sticky rice” for gay Asian/Pacific Islander endogamy). Josh, Henry’s dead lover, was Jewish, not Chicano, so at least a minority if not the same one.

I have probably made the changes in Henry’s life sound too good to be true. Indeed, they seem a combination of politically correctness and wish-fulfillment. However, drugs, violence, societal prejudices of various sort and convoluted California politics are in the foreground. Henry may yet live “happily ever after,” but it has not and will not be all that easy. He’s a fairly prickly dude, easily rubbed the wrong way by Elena and Vicky. Nonetheless, readers of the novel and/or of the series of novels are certain to wish him—and his creator who is also a Sacramento barrio-born, Stanford-trained lawyer who practiced until recently in LA—well. What I have read of Nava’s openly autobiographical writings, about growing up in a city where two rivers (rios) merge, promises a continuing post-Henry Rios yield of crisp analytical prose.

Nava’s prose is very readable; the repartee in and out of court is snappy. Although Elena is less than a fully developed character, Vicky and Vicky’s stepmother are. And Henry is a sympathetic brown porcupine, trying to hold back his quills and let some other people get close to him after the near-despair and near-death with which the novel starts.

* In 2016 Nava published a revised and expanded version (he says only 5% of the text is unchanged) of his first novel, The Little Death (2001), as Lay Your Sleeping Head. The volume includes a substantial memoir of his starting to write, including a tribute to Joseph Hansen with whom he lunched weekly when he was an LA prosecutor, and a recollection of dismay at the doomed gay (exclusively white) men in 1970s fiction published in New York (Nava’s first two novels were published by Alyson in Boston).

published by epinions, 4 May 2001

©2001, 2016, Stephen O. Murray