Paul Benard:

Mattachine Misfit

Profile by David Hughes

Posted March 31, 2017

Introduction

In my time looking at the lives of members of the early Mattachine, perhaps the most enigmatic was Paul Benard (April 24, 1916–November 7, 1954).

One of the eight men pictured in the famous “Christmas tree” photograph taken by Jim Gruber in 1951, Benard turns out to have been considered for a role in the Mattachine’s leadership. He left the group and left Los Angeles but remained in contact with members, only to die in 1954.

To my surprise last year, a chance query by Víctor Macías-González, Professor of History and Women’s, Gender, and Sexuality Studies at University of Wisconsin–La Crosse provided me with Benard’s birth name, and I was able to construct a very detailed account of his early life. Had the existing Mattachine leadership known about his involvement in the “little” and leftist theater endeavors of New York, San Francisco, and Los Angeles, they’d have seen him as a comrade.

The following is adapted from my work-in-progress with the working title The Feeble Strength of One: Bob Hull, Chuck Rowland, Maxey, Marx and the Mattachine. Because its length likely would prevent its eventual publication as-is, I offer it here. Lengthy as it is, more study of Paul Benard is warranted.

I dedicate this to Stuart Timmons (1957–2017), an old friend whose writing about Bob Hull, Chuck Rowland, and Wallace de Ortega Maxey in The Trouble with Harry Hay (1990) and Gay L.A.: A History of Sexual Outlaws, Power Politics, and Lipstick Lesbians (2006) first propelled me to look into the life of Bob Hull with whom I share the Hull surname, through my mother Phyllis J. (Pankonin) Hughes.

Bob and Paul

In early 1952 Mattachine cofounder Bob Hull took up with Paul Benard, an actor and writer who had become involved in the organization and was being considered for entry into the Fifth Order, the group’s top echelon.

Paul Charles Benard was born Charles Roy Coté Jr.[1]I am grateful to Víctor M. Macías-González, Professor of History and Women, Gender, and Sexuality Studies, University of Wisconsin, La Crosse, for providing me with Benard’s birth name. on April 24, 1916 in Lowell, Massachusetts, to Lowell native Charles Roy Coté, a machinist, and mother Eleanor F. (Smith) Coté, a native of Provincetown.[2]“Massachusetts State Vital Records, 1841–1920,” database with images, FamilySearch (https://familysearch.org/pal:/MM9.3.1/TH-1971-26787-1727-46?cc=1928860 : accessed 23 April 2016), Births > … Continue reading His parents are listed in Lowell’s city directory for 1917 and 1918 but are absent in the directory thereafter.[3]The Lowell Directory 1917, Boston: Sampson & Murdock Co., 219; The Lowell Directory 1918, Boston: Sampson & Murdock Co., 221. Charles Jr.’s mother died in Lowell in 1921, when he was about five years old.[4]Ancestry.com. Massachusetts, Death Index, 1901–1980 [database on-line]. Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2013. Original data: Department of Public Health, Registry of Vital Records … Continue reading In 1930, a few days before his fourteenth birthday, he was living or staying in Lowell with his grandfather, also named Charles Coté, an ice company stableman, and grandmother Annie (Baker) Coté.[5]U.S. Census, 10 Apr 1930, Lowell, Middlesex Co., Mass., Enumeration Dist. 9084, Sht. 21-A, lines 24, 25, 27. Paul Benard’s father doesn’t appear in this census as indexed by Ancestry and … Continue reading That June he graduated from Bartlett Junior High in Lowell, reciting in the ceremony “Our Flag”—“When you see the Stars and Stripes displayed, son, take off your hat. Some may titter”—attributed to Alvin M. Owsley, a past National Commander of the American Legion.[6]“Bartlett Graduation,” Lowell Sun, 23 Jun 1930, 9. Owsley’s position in the American Legion is mentioned in “Alvin M. Owsley, Diplomat, is Dead,” New York Times, 04 Apr 1967, 43. His … Continue reading

Charles Jr. may not have been aware of Owsley’s threat to overthrow the U.S. government should “freedom” be “menace[d]” by “soviets, anarchists, I. W. W.’s, revolutionary socialists and every other ‘red’” in the same way “as the Fascisti of Italy fought them”—reassuring his interlocutor, “I do not think that time is going to come.” Owsley’s reference to Italy was not in passing. “Do not forget,” he said, “that the Fascisti are to Italy what the American Legion is to the United States,” explaining that Mussolini had been the commander of ex-servicemen in his own country.[7]Quoted from “an exclusive interview” with the Newspaper Enterprise Association on or about 02 Jan 1923, as reported in the Daily Ardmoreite [Ardmore, Oklahoma], “American Legion Head Believes … Continue reading

Charles II

Young Charles Coté’s organizational and theatrical pursuits are told in the pages of The Lowell Sun newspaper, beginning in October 1932. This also is the month of the birth of his half-sister Joyce Ann, his father having married Josephine Keohane, herself a Lowell native.[8]“Joyce Ann Glaze,” The Day [New London, Conn.], 23 Sep 2010; this obituary calls Joyce’s mother Joan rather than Josephine. No marriage record has been obtained. Charles and Josephine are … Continue reading Three dozen articles in the Sun between 1932 and 1935 mention Charles Jr.’s involvement in many activities, beginning with an athletic field dedication.[9]“Chelmsford to Dedicate New Field with Big Celebration,” Lowell Sun, 06 Oct 1932, 17. He attended only three years of high school in Chelmsford, a Lowell suburb, between 1930 and 1933, indicating he skipped a grade.[10]“Chelmsford Exercises,” Lowell Sun, 22 Jun 1933, 1. In May 1933, he had a role in his senior play, A Lucky Break, set in rural Connecticut,[11]“Annual Play Presented,” Lowell Sun, 12 May 1933, 5. the Broadway debut of which was panned by the New York Times, but noted by the Wall Street Journal, charitably: “It is difficult to estimate the draw of ‘A Lucky Break’ with New York’s overwise public, but it seems safe to predict popularity for it in the wide open spaces where men are men, etc.”[12]“‘A Lucky Break’ is Mildly Amusing,” New York Times, 12 Aug 1925, 16; “Making Dreams Come True,” Wall Street Journal, 13 Aug 1925, 3. Coté was co-composer of the “class ode” sung at his high school graduation by the diplomates as they left the stage.[13]“Chelmsford Exercises.” Immediately he was elected to the general committee of the high school’s alumni association, which had been inactive “for some time.”[14]“Alumni Reorganizes [sic],” Lowell Sun, 30 Jun 1933, 7. Over the late spring and summer, Coté appeared in a variety of performances, from minstrel shows to an audition for radio, a field in which he later became involved.[15]“Annual Exhibit by 4-H Club Groups,” Lowell Sun, 24 May 1933, 9; “Chelmsford News,” Lowell Sun, 23 Aug 1933, 5. In the fall, Coté had a major role in Chelmsford’s annual harvest festival, both on stage and co-directing.[16]“Chelmsford Prepares for Johnson High,” Lowell Sun, 27 Oct 1933, 4. During this time, most of his theatrical work was on the lighter side, with one review saying he provided “side-splitting comedy” at a standing-room only performance.[17]“‘Breezin’ Along’ Attracts Crowd at Chelmsford,” Lowell Sun, 26 Jan 1934, 17. After performing a vaudeville routine at St. Mary’s parish annual lawn party on August 1, 1935, Charles Roy Coté Jr. vanished from the Sun’s pages for two years, reappearing in the fall of 1937 as Paul Benard—or Bernard—the first of many such misspellings.

Little Theater

“Finds Success in Theatrical Field in N.Y.,” reads a headline in the November 11, 1937 edition of the Lowell Sun. The story tells of Benard’s nom de scène[18]At some point Charles Roy Coté appears to have assumed the name Paul C. Benard legally, since he registered to vote under that name in 1952. Index to Register of Voters, Los Angeles Precinct No. … Continue reading and his “outstanding work as producer with Little Theatre groups in and about New York,” having “served as producer with the Little Theatre group of Jamaica, Long Island.”[19]“Finds Success in Theatrical Field in N.Y.,” Lowell Sun, 22 Nov 1937, 9. It’s possible that the Little Theatre group of Jamaica, Long Island was Contemporary Theatre, founded there by Wilson … Continue reading

Little theaters were small, homegrown venues scattered across the country. “They had to be small to match the pocketbooks of the new producers,” writes Kenneth Macgowan (1929, 25), “but they could never have been large without violating the idea behind the new plays and new productions’ psychological and emotional intimacy.” According to Dorothy Chansky (2004, 4), proponents of little theater “refuted […] primarily a large network of touring shows from New York (as well as the New York productions themselves) that included […] euphemistic realism, a style in which images of urban existence, recognizable social types, real places, or social problems are depicted, but in such a way as to avoid, for the most part, creating images that are too harsh or disturbing to mainstream sensibilities.” Douglas McDermott (1993, 15) writes that “live theatre persists because it offers an alternative image of society to an audience that desires one.”

That alternative found flower in workers theater groups that sprung up in the 1920s, from semi-professional to agitprop companies, as discussed by historian Annette T. Rubinstein in her brief survey, “The Cultural World of the Communist Party.” The ’30s brought groups with names like Harlem Suitcase Theater, New York Workers Laboratory Theater, and Theater Union (Rubinstein 1993, 248–249). The 1937 Sun article cited above is an announcement of Paul Benard’s appointment as director of Organized Theatre of New York, a “group [that] regularly produces plays […] and boasts many members who have had Broadway experience.” The nature of those plays was not disclosed.[20]“Finds Success in Theatrical Field in N.Y.” Benard’s partners in the Organized Theatre venture were “Marian Capstone, former director of the Park Lane Players of Philadelphia; Margaret … Continue reading Regardless of its character, in the Depression of the ’30s, Benard’s company worked in what Rubinstein (257) calls “the only time since Elizabethan England when an English-speaking stage found itself the center of a national culture.”

Contemporary Theatre and Contemporaries

The next spring of 1938, Paul Benard was mentioned in the Lowell Sun as director of another theater company, New York City’s Contemporary Theatre, which was to mount summer stock productions in Lowell. On June 11, Benard and three other company staff had met in Boston with actor Burgess Meredith as he toured with Lillian Gish in The Star-Wagon (which had enjoyed a six-month run on Broadway[21]“Anderson’s Drama about ‘Time Machine’ Comes to Chicago,” Chicago Tribune, 10 Apr 1938, E2.), with Meredith agreeing to chair the company’s advisory board.[22]“Summer Stock Opens Here,” Lowell Sun, 14 Jun 1938, 8. Oddly the Sun omits mention of Benard’s having been “last seen on Broadway with Burgess Meredith in ‘Star-Wagon’,” which was noted four years later when Benard had relocated to Phoenix, Arizona.[23]”Opening Due For Musical,” Arizona Republic, 09 Apr 1942, 8. Benard doesn’t appear in The Star-Wagon’s original cast roster as published in the New York Times, 30 Sep 1937, 18. … Continue reading

Meredith was in top form at the time. That fall the New York Times would call his performance in Star-Wagon that of “a fully awakened actor.”[24]“The Play,” New York Times, 30 Sept 1938, 18. The Chicago Tribune wrote earlier that his “rise within the last four years has been the most brilliant single achievement on the American stage.”[25]“Anderson’s Drama about ‘Time Machine’ Comes to Chicago.” That same year of 1938, Meredith had been acting president of Actors’ Equity, the stage actors union.[26]“Byron is Elected Equity President,” New York Times, 28 May 1938, 9. Years earlier, he had been involved in an insurgent group within Equity. “Meredith is a forthright young man,” writes Theatre Arts Monthly, “intelligent enough to decline stardom, belligerent enough, as his activity in the Actors’ Forum indicates, to strive for attainment of his purposes.”[27]“Personae Gratae,” Theatre Arts Monthly, January 1936, 52. Those purposes, at least as articulated during Actors’ Forum’s initial attempt to usurp Equity incumbents in 1935, included “pay for rehearsals, abolition of the junior minimum wage”—apparently a two-tier compensation scheme—“and some form of unemployment insurance.”[28]“Threat of Schism Halted by Equity,” New York Times, 02 Mar 1935, 19.

Regarding Benard’s Contemporary Theatre, Meredith had much praise, calling it “the finest ‘group theatre’ in the United States. The energy and ability shown by its members is [sic] worthy of recognition by all members of the theatre world.”[29]“Summer Stock Opens Here.” “This evening will mark an important event in the theatrical history of Lowell,” wrote Sun theater columnist Charles Sampas on June 17, 1938 regarding Contemporary Theatre’s twelve-weekend run. “It marks the first time in many years that a professional New York company has played in Lowell, and it is the first time in the history of the city that a summer theatre has been established.”[30]“N. Y.–Hollywood,” Lowell Sun, 17 Jun 1938, 18.

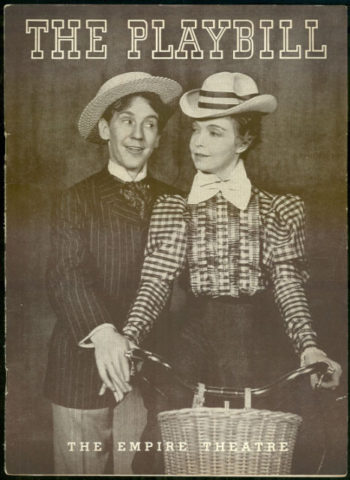

But Sampas wouldn’t write another word about the company for some time. Despite the hype, Contemporary Theatre flopped in its June 1938 debut weekend’s performance of A. A. Milne’s Dover Road, a play that had received stellar reviews on Broadway in 1921.[31]I found no mention of, nor review of Dover Road in the Lowell Sun following its 17 Jun 1938 debut. Regarding the play’s Broadway debut see “Several Cheers for Mr. Milne,” New York … Continue reading “Thespis is dead….locally,” wrote Sampas nearly seven weeks later. “The Nabnassett Players”—from the village of the same name, ten miles east of Lowell, who performed in Westford, three miles further—

have hied themselves to Manhattan, to bask under the minarets of the Magic Town….The Contemporary Theatre group, too, has said Farewell to Lowell….The Contemporary Theatre, ambitious lads and lassies, gathering mental encouragement from that famed New York Group theatre, was the first to collapse….Their efforts to present modern-day ‘in the flesh’ drama at the Rex auditorium went for naught.[32]“N. Y.–Hollywood,” Lowell Sun, 03 Aug 1938, 16. By “that famed New York Group theatre” Sampas refers to the company that staged Clifford Odets’s Waiting for Lefty, causing the New York … Continue reading

Some disambiguation is called for at this point. In May of 1936, Wilson Williams, an African American from New Jersey who in 1934 had precociously conducted a “survey of the Negro Theatre,”[33]“Theatrical Jottings,” Pittsburgh Courier, 15 Sep 1934, A9. By way of perspective, Harlem’s American Negro Theater, alumni of which include Ruby Dee, Ossie Davis, and Harry Belafonte, would not … Continue reading founded the Contemporary Theatre in Jamaica “for the purpose of developing a theatre for Queens with no racial barriers,” according to the New York Amsterdam News.[34]“Princeton Youth Returns to Dance,” Trenton Evening Times, 17 Feb 1938, 20; “Queens Theatre Announces Play,” New York Amsterdam News, 16 Jan 1937, 8. Also in May 1936, a group calling itself The Contemporary Theatre staged a single performance of Clifford Odets’s popular Waiting for Lefty at a labor hall in Brooklyn.[35]Display ad for 29 May performance appearing in Socialist Call, 30 [sic] May 1936, 11. Two weeks later the “Contemporary Theatre, a cooperative group” presented Pins and Needles, billed as “a satirical musical review,” sponsored by an American Federation of Labor affiliate. The Pins and Needles players had coalesced under the Contemporary Theatre moniker after having presented scenes in April from Richard Rohman’s Power of the Press, based on the 1935 strike at the Newark Ledger.[36]“Pointed Labor Revue Sticks Stuffed Shirts,” Socialist Call, 20 Jun 1936, 11; “Present Revue Again,” Socialist Call, 27 Jun 1936, 11. If Benard had been involved in these sorts of productions, he and Mattachine Society cofounder Harry Hay would have had something about which to compare notes, Hay having been involved in West Coast productions of Waiting for Lefty in 1935 (Timmons 1990, 72–74).

Aside from this, as early as February of 1937 Wilson Williams had joined the Negro Concert Dance Group.[37]“The Dance,” New York Times, 28 Feb 1937, 8X. In April 1938, still identified as a Jamaica, Queens “native,” Williams gave his first solo recital.[38]“Young Dancer in First Solo Recital,” New York Amsterdam News, 26 Mar 1938, 16. By January 1939 he had formed his own Negro Dance Company.[39]“The Dance,” New York Times, 22 Jan 1939, 8X. Given the demands of Williams’s dance career, it’s possible that Paul Benard worked with Williams’s theater group in Jamaica, Queens and then even took the reins of the “New York” Contemporary Theatre prior to its 1938 summer stock stint in Lowell. Whatever the case, Benard did not appear to have “hied” himself to Manhattan after the flop of Contemporary Theatre’s Dover Road. A month later he was in Westford with the Nabnasset Summer Theatre, receiving favorable reviews in a production of Harry R. Irving’s Because We’re Here followed by Work for the Giants by Elizabeth McCormick.[40]“N. Y.–Hollywood,” Lowell Sun, 15 Jul 1938, 18; “‘Work for the Giants’ Scores at Nabnasset Summer Theatre,” Lowell Sun, 19 Jul 1938, 15; “Strawhat Bookings,” Variety, 31 … Continue reading Nabnasset’s final production was “a modern version” of Shakespeare’s The Taming of the Shrew. “As Grunio, Petruchio’s valet,” a local review read, “Lowell’s Paul Benard is a distinct hit, his antics truly convulsive.”[41]“Shakespearean Play Presented at Nabnasset,” Lowell Sun, 26 Jul 1938, 15.

Blackfriars

Having evidently abandoned New York City, six months later in January 1939 Paul Benard organized another theater group in Lowell, a local branch of the Blackfriars Guild, a Catholic drama organization. On January 29, Benard gave a public talk in Lowell titled “The American Theatre Conference and the Catholic Theatre Conference.” He led off his discourse with some of the practical concerns raised at the May 1937 ATC parley, none of which had been acted upon during the eighteen months since the conference.[42]The conference had been held 24–27 May 1937, at New York City’s Hotel Astor (“The Theatre Convention,” Wall Street Journal, 26 May 1937, 13). As Benard told his listeners regarding those concerns, “One of the chief faults in the modern American theatre” had been overlooked: “its geographical limitation to a cluster of side streets off Broadway in New York city […]. Another fault, the fact that the theatre is dominated by a group of producers whose chief interest in the theatre is profit, was not even considered.”[43]“Discusses Aims, Purposes of Blackfriars Guild,” Lowell Sun, 31 Jan 1939, 9. The little theater movement was meant to be corrective of this status quo, but a limited one, of which Benard likely had been aware even before the collapse of his summer stock venture the summer of 1938.

One element for success that the little theater movement lacked, the Catholic Church had: small-scale infrastructure, already underwritten, “consisting of some 10,000 parish and school halls,” as Benard put it in his talk.[44]“Discusses Aims, Purposes of Blackfriars Guild.” While the ATC conference had been attended by 500, and included sessions featuring producers, writers, actors, a Congressman, Federal and municipal theater managers, the public, et al.,[45]“Theatre Convention,” New York Times, 25 May 1935, 32; “Theatre Convention,” New York Times, 16 May 1935, 165. the Catholic conference, held in June 1937 in Chicago, was more, well, parochial in prospective attendance: 300 players and playwrights, parish drama group directors, and teachers.[46]“Catholics Will Confer on New Theater Plan,” Chicago Tribune, 06 Jun 1937, SW1. The number of attendees was given by Benard (“Discusses Aims, Purposes of Blackfriars Guild”). The latter conference also was more realistic in its assessment of challenges, according to Benard. “None of the leaders had any illusions about the calibre of the average Catholic company,” he said. “Among the problems to be faced were lack of lists of good plays and lack of training.”[47]“Discusses Aims, Purposes of Blackfriars Guild.” The Catholics then called a convention in Washington D.C. in August attended by more than 700, electing an executive board that opened offices for the Catholic Theater Conference at Catholic University of America.[48]“New York Man Heads Catholic Theater Group,” Washington Post, 09 Aug 1937, 13.

Continuing in his talk in Lowell, Benard explained, “The Blackfriars guild is an active and highly specialized part of the conference. Its aim is to sponsor and unify Catholic dramatic organizations of superior ability. The specific purpose of the guild as stated in its constitution is to promote the study, representation and writing of drama which shall be consistent with the recommendations of the Catholic church.”[49]“Discusses Aims, Purposes of Blackfriars Guild.” This raises the question of how Benard reconciled Church dictates with the “in the flesh” drama he’d attempted to stage with Contemporary Theatre in Lowell. Was his Blackfriars work some sort of extension of the little theater work he’d done in Queens? Was it subversive? Or merely mercenary?

The Lowell Blackfriars’ first production, under the direction of Benard, was to be Emmett Lavery’s The First Legion,[50]“Discusses Aims, Purposes of Blackfriars Guild.” a play dealing with the human side of a Jesuit cloister.[51]“The Theatre,” Wall Street Journal, 16 Oct 1934, 3. Upon the play’s Broadway debut, a former chair of the Pulitzer Prize Jury for Drama chastised New York’s press for having not sent its “first string” of critics; the “second or third string reviewers […] appeared to be afraid to praise the play, because they were somewhat skeptical of the box-office appeal of a piece which contained no women, no sex, and no element of romantic sentiment” whereas “the eager response of the audiences […] appears to indicate that there is a place in the theatre for a spiritual drama which is not only noble in intention but also quite astonishingly skillful in execution.”[52]“On ‘The First Legion’,” New York Times, 28 Oct 1934, X2. Two years later Paul Benard would offer his own critique of San Francisco critics, as will be seen.

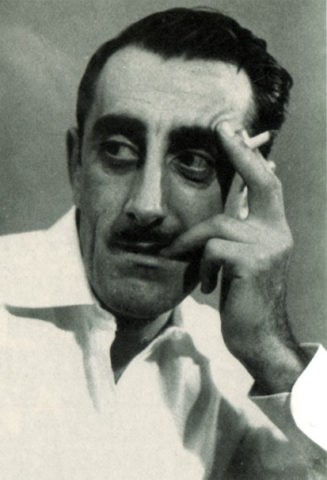

But aspiring thespians of Lowell evidently needed more cajoling: three weeks after his January lecture, on February 17 Benard repeated his talk, now titled “The Place of the Blackfriars in the American Theatrical Scene.”[53]“Blackfriars Guild,” Lowell Sun, 15 Feb 1939, 6. The cast for The First Legion wasn’t announced until two weeks later.[54]“Announce Cast for Blackfriars Production,” Lowell Sun, 03 Mar 1939, 12. The play’s March 9 performance was well received by the Lowell Sun’s reviewer as well as its eight hundred viewers; the play was to be repeated the next Tuesday. While several in the cast were singled out for their performances, Benard only was mentioned in passing. To my knowledge this review contains the only extant Sun photograph of Benard, who appears to wear a gray wig in a group shot with ten other actors.[55]“Blackfriars Score Complete Success,” Lowell Sun, 10 Mar 1939, 15. I was able to locate only one other image of Benard in all the press he obtained.[56]The other photograph accompanies his biographical essay, “Playwright Has Jitters As Curtain Time Nears,” Arizona Republic, 14 May 1950, 3:5. This is curious because when he came to work with the Mattachine Society Benard was passed over for a leadership spot, the consensus being that he was more interested in his career than the organization, as discussed below.

It was during the lead-up to Legion’s staging that Paul Benard was identified as also involved in radio. “He is known as the director and producer of the popular radio program, the Radio Playhouse,” a March 6 story read,[57]“Assign Roles in ‘The First Legion,’” Lowell Sun, 06 Mar 1939, 4. referring to an apparently local production.[58]At the time, reporter Charles Sampas, in the course of introducing Lowell readers to a new local theater group, mentioned six others, including “the Radio playhouse” (“Young People Score in … Continue reading A month later, Benard portrayed Judas in the Playhouse drama, Thirty Pieces of Silver, “for the Holy Week presentation of this well-known weekly program.” So well known was Radio Playhouse in Lowell that its position on the dial is not mentioned.[59]“Lenten Drama on Radio Tonight,” Lowell Sun, 05 Apr 1939, 7. Benard is identified as “producer of the Radio Playhouse.”

In April 1939 “a newly organized group,” The Drama Guild, featured Benard in a one-act, Stephen, “a comedy-farce dealing with a husband and wife whose lives were constantly made disagreeable by the wife’s interest in psychoanalysis.”[60]“Speakers Club Holds Dinner-Meeting,” Lowell Sun, 26 Apr 1939, 8. It’s possible this was a Blackfriars Guild presentation.[61]For instance, in June columnist Charles Sampas identified the Blackfriars Guild as The Blackfriars Drama Guild (“Sampascoopies,” Lowell Sun, 13 Jun 1939, 15).

Blackfriars Bombshell

In May it was announced that the Lowell chapter of the Blackfriars Guild had been selected from more than two dozen such guilds to present the first production of the national organization’s summer stock stint at the nearby theater in Westford beginning June 28.[62]“Blackfriars Take Over Westford Summer Theatre,” Lowell Sun, 09 May 1939, 5. This larger effort, Blackfriars’ Repertory Theatre, consisted of chapter directors and their most talented players. Benard, identified as director of the local guild, was selected as the repertory’s co-director. After its ten weeks in Westford, the repertory was slated for a coast-to-coast tour.[63]“To Cast for Guild Play,” Lowell Sun, 05 Jun 1939, 8.

On May 26 Benard directed the local guild, acting the lead, in The Monkey’s Paw, which Benard had performed with Contemporary Theatre at Greenwich Theatre in Manhattan.[64]“Miss Horne Joins Blackfriars Guild,” Lowell Sun, 19 May 1939, 10. I found no mention of the New York production in the New York Times. The Lowell production was a fundraiser to aid in the upkeep of the theater in Westford.[65]“Blackfriars’ Play,” Lowell Sun, 24 May 1939, 10. The Lowell Sun’s Charles Sampas praised the play, writing, “Mr. Benard is not only a most capable director—but a superlative actor,” saying that he portrayed the lead character “magnificently.” (Sampas twice likened Benard’s appearance to that of actor Basil Rathbone.[66]“Sampascoopies,” Lowell Sun, 13 Jul 1938, 13; “Sampascoopies,” Lowell Sun, 16 Jun 1939, 20.) The critic also noted the company’s initiative: “It may be safely stated that it was by far one of the most ambitious undertakings by any local theatrical group.”[67]“Blackfriars Add Much to Little Theatre Renaissance,” Lowell Sun, 27 May 1939, 3.

Philip Barry’s Holiday[68]A film adaptation of Holiday had been released the year before, starring Katherine Hepburn and Cary Grant, and directed by George Cukor. The three already had worked on the brash Sylvia … Continue reading was slated to be the first Blackfriars’ Repertory production, presented by Lowell’s guild. Casting of the leads, however, was not left to chance. “When it was decided, several weeks ago, that the Lowell chapter would open the 10-week season […],” wrote the Sun, “it was felt by the national officials that perhaps the local chapter could not boast of two players capable,” and thus a national competition was launched among the now-twenty-three chapters. Lowell’s leads won the contest—barely three weeks before the July 5 staging. The supporting cast, including the play’s director Paul Benard, also was announced.[69]“Local Blackfriars to Take Leading Roles in ‘Holiday’,” Lowell Sun, 12 Jun 1939, 7. A week later, the cast so proudly touted on June 12 had been scrapped on the 18th, as reported in the Sun. With no explanation, a two-paragraph item on June 19 reads like an initial casting call.

Casting for the play “Holiday” was begun yesterday at an important meeting of members of the Lowell Blackfriars guild […]. A session of the board of directors was held prior to the general meeting.

President William Hornbrook conducted a brief business meeting, and introduced the [play’s] new director, Myles Finnegan, of [nearby] Billerica. Arthur Cryan, a director, reported that Rev. Urban Nagle, O. P., would be in charge of the Westford theatre following the presentation of the play by the local group. Those who show special talent this summer will have a chance to become a member of the National Repertory theatre of the Blackfriars guild, and will go on the road with a living wage salary.[70]“Blackfriars to Present ‘Holiday’,” Lowell Sun, 19 Jun 1939, 15.

Benard apparently lost his co-directorship of the national Repertory Theatre, his spot as director-actor in Holiday, and some of his cast. As late as June 13, columnist Sampas had noted that Benard’s female lead for Holiday, Elaine Horne, “may forego Bar Harbor” (perhaps a summer vacation in the birthplace of the Rockefellers in Maine?) “for her Thespian duties here with The Blackfriars Drama Guild.”[71]“Sampascoopies,” Lowell Sun, 13 Jun 1939, 15. Out of nine cast members previously announced, five were retained, but Benard and his leads were gone. The Sun called the production “a brilliant success” for the “acting, settings, lights and general performance.”[72]“Catholic League Sponsors Play,” Lowell Sun, 07 Jul 1939, 8.

With this, Paul Benard disappears from Lowell, but his father surfaces the next year in 1940—with a new wife, Lowell native Josephine V. (Keohane) Coté, and eight-year-old daughter Joyce.[73]U.S. Census, 02 Apr 1940, Lowell, Middlesex Co., Mass., Enumeration Dist. 18-47, Sht. 1-B, lines 68–70. Josephine Keohane appears to have been unmarried at the time of her mother’s death 25 Apr … Continue reading By 1941 these Cotés had moved to the seaport town of New London, Connecticut, where they remained into the elder Charles’s retirement.[74]New London […] Directory, 1941–42, New Haven: Price & Lee Co., 180; New London City Directory 1965, New Haven: Price & Lee Co., 237.

The Sun’s last mention of Paul Benard, June 16, 1939, is perhaps a portentous passage by Paul Sampas in the Meandering section of his “Sampascoopies” column. Juxtaposed with a photocollage of portraits for the film Juarez, costarring Lowell native Bette Davis: “That very excellent Thespian, Paul Benard, climaxing a laconic stroll with a sudden turn in a burst of dramatic zeal, nearly knocking us down.”[75]“Sampascoopies,” Lowell Sun, 16 Jun 1939, 20. A Paul Bernard was mentioned three weeks later in conjunction with a show in Abdingdon, Virginia. Robert Porterfield’s Barter Theater was staging a new play, SUsquehanna 7, by Alfred Osgood.[76]“Summer Theaters…,” Brooklyn Eagle, 09 Jul 1939, 6. The theater, which accepted in-kind donations of food in lieu of admission, was begun in 1933 “when there was a surplus of actors without food, and a surplus of unsalable food among farmers,” according to an AP profile dated upon the theater’s June 8 opening. “The players receive only room and board plus experience that Porterfield claims they could get nowhere else.” For that 1939 summer season Porterfield had interviewed 673 applicants in New York for seventy players and a crew of ten.[77]“Virginia Barter Theater Is Profitable Experiment,” AP via Hartford Courant, 16 Jul 1939, A1; “Barter Theater To Open Season With Presentation Of ‘Our Town’,” … Continue reading Although it’s a stretch to speculate that Paul “Bernard” might have interviewed with Porterfield in New York, just when he was involved with the Blackfriars in Lowell, Benard might have been hungry enough, as he admitted a decade later, to barter.

Phoenix

Ten years later, in a brief 1950 autobiographical and professional sketch of his life during the 1940s, Benard provided a timeline that is difficult to shoehorn into gaps of the public record.

I had hitch-hiked from New York to Los Angeles on the tail of a depression, armed with a youthful dream of life in Hollywood. After six months I woke up and started back for Broadway. Phoenix looked pretty good and I decided to look around and found a job at Camelback [Inn in the winter of 1940]. My first customer as a room-service waiter was Gene Kelly. As I carried the tray from the kitchen to the casa, I trembled, I shook, I quivered. This was my first job in more than three years and I had to keep it.

When the 1940 winter season closed, Jack Williams took a chance on me at KOY; previous writing experience—letters and postal cards.[78]“Playwright Has Jitters As Curtain Time Nears,” Arizona Republic, 14 May 1950, 5. This quote has been reconfigured for continuity.

This account omits Benard’s time in San Francisco in 1940 and 1941.

San Francisco

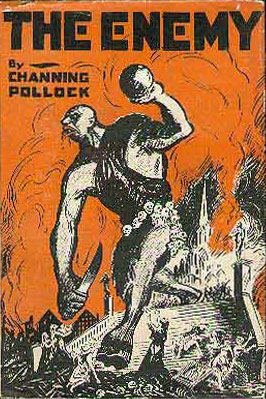

By March 1940, Paul Benard had moved to San Francisco and formed a new incarnation of Contemporary Theatre: Contemporary Theater.[79]While what follows indicates that Benard was a founder of Contemporary Theater, California Secretary of State’s Business Programs Division contains a file, C0161294, Contemporary Theater, Inc., … Continue reading Benard and one Pat McCann were “at the head of the organizational work,” according to a March 8 story in the San Francisco Chronicle. The aim of the company was no less than “to bring active, full-time legitimate theater to San Francisco.” Its first production was to be The Enemy by Channing Pollock.[80]“New Theatrical Company Formed,” San Francisco Chronicle, 08 Mar 1940, 10. Benard is listed in the Index to Register of Voters dated 26 Sep 1940 for the City and County of San Francisco, … Continue reading The choice was provocative given the play’s antiwar theme, eight months before the U.S. would engage in yet another war.[81]The Chronicle called The Enemy “Channing Pollock’s famous drama of war propaganda” in a notice regarding the play’s film adaptation directed by Victor Seastrom and starring Lillian Gish … Continue reading The company’s next production was Eugene O’Neill’s The Great God Brown with Benard both directing and in the cast.[82]“‘Great God Brown’ At French Theater,” San Francisco Chronicle, 25 Apr 1940, C6. Years earlier Chronicle drama editor George C. Warren had seemed resentful of that play’s NYC success, writing that it “is doing […] well in Greenwich Village, despite its excessive symbolism—the principle characters carry masks which they put on to represent their face to the world, and remove when they are alone or with people whom they know well enough to be natural,” gestures that would resonate with those who eventually were drawn to the Mattachine.[83]“Behind the Back Row: O’Neill Play To Continue In New York,” 27 Feb 1926, C7. Warren’s position with newspaper is identified in the Chronicle’s obituary for his wife, “Mrs. Warren Dies … Continue reading Trumpets of Wrath was the company’s June 1940 production directed by Benard—the West Coast premiere of a World War I drama by William Kozlenko, editor of One Act Play Magazine and Radio-Drama Review.[84]“‘Trumpets of Wrath’ At Contemporary,” San Francisco Chronicle, 13 Jun 1940, C8. Benard directed trios of one-acts in September and October, the latter being plays by William Saroyan.[85]“Three One-Acters At Contemporary Theater,” San Francisco Chronicle, 04 Sep 1940, C10; “Three Saroyan Plays To Be Presented,” San Francisco Chronicle, 14 Oct 1940, C10. November’s offerings, also directed by Benard, were the temperance drama Ten Nights in a Barroom followed by a throwback to Benard’s youth: a “Gay Nineties Minstrels” afterpiece. These apparently were so well received as to be repeated a week later.[86]“Contemporary Group To Play Melodrama,” San Francisco Chronicle, 11 Nov 1940, C9; “An Old-Timer at The Contemporary,” San Francisco Chronicle, 22 Nov 1940, C8. It’s as if Benard was putting his audience to the test by giving them what they wanted.

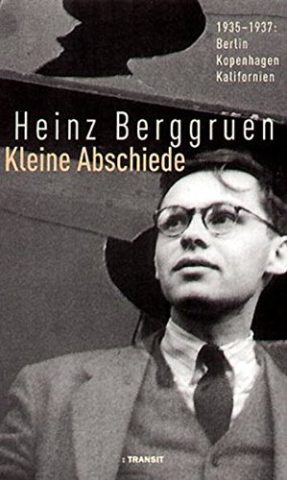

Contemporary Theater received no reviews by the Chronicle until after Benard blasted the newspaper’s drama critics for lamenting what they saw as the death of theater in San Francisco. In his December 1940 letter to the editor, Benard insisted, instead, of local theater’s vibrancy: “over 80 little theater groups in San Francisco, of which a dozen play to regular bimonthly audiences; there are over 1000 persons engaged in this little theater work […].” Benard wrote, “Rather than discouragement, we need co-operation. Send your critics to see our productions—and send them with open minds.” Send critics they did and the result was a lengthy pan of April 1941’s Topical Fever, Benard and collaborators’ “self-styled satirical revue based on the current problems of the day,” as the reviewer put it, “with particular emphasis on war, the draft and aid to Britain.” The critic didn’t blink or even wink when praising two of the evening’s sketches by Heinz Berggruen, who until recently had been the Chronicle’s assistant art and music critic.[87]Berggruen’s position with the Chronicle is mentioned in “Heinz Berggruen, Music Critic, Weds,” San Francisco Chronicle, 12 Aug 1939, C9. Berggruen’s sketches “brightened the whole evening—‘His Name is William,’ a very discerning satire on the love-of-life spirit that is Mr. Saroyan, and ‘A Masterpiece A Masterpiece,’ with Gertrude Stein under the scalpel.” Other actors were praised, as were the sets, but Benard was not. “The carrier of this theatrical malaise is an earnest young men [sic] […] whose taste in matters of the theater […] runs to the ‘blue’ of more uninhibited style in exhibitionism.” Benard wrote eight of the twenty-seven songs and sketches, appearing in ten, “not always to his advantage.” The show was “an ill-advised attempt to furnish entertainment, if that was Mr. Benard’s aim.”[88]“A Satirical Revue With Difficulties,” San Francisco Chronicle, 22 Apr 1941, C7. With this, Benard vanishes from the pages of the Chronicle, which is notable because earlier that year he’d been involved in the formation of the San Francisco Theater League, which sponsored Contemporary Theater’s production of Saroyan’s My Heart’s in the Highlands at the League Playhouse.[89]“Don’t Look Now—It’s Saroyan Again!” San Francisco Chronicle, 04 Mar 1941, C6. This was followed by a League-sponsored lecture on the topic of the “revolutionary theater of Russia, led by the Moscow Art Theater,” to be delivered by Alexander Kaun, a UC professor “and a well known student and authority on Russian culture.”[90]“Lecturer,” San Francisco Chronicle, 27 Mar 1941, C7. Kaun was mentioned in reports on un-American activities in California, including his sponsorship with dozens of others of a pamphlet … Continue reading The San Francisco Theater League itself would not be mentioned again by the Chronicle.

Phoenix Rising?

Benard was back in Phoenix by the winter of 1942, having been hired as director of dramatic programs at radio station KOY.[91]“Benard To Teach Class In Acting,” Arizona Republic, 30 Jan 1949, 10. He was introduced as Paul Charles Benard to the city’s theatergoers on April 9 in the pages of the Arizona Republic as the “professional director” of a newly organized thespian group whose appellation gave the nod to earlier workers theater troupes: We, the Players. The group’s “Phoenix debut” was to be It’s Fun To Be Free, a cast-written musical show “of satirical nature, poking fun at current social and cultural trends and contemporary personalities”—echoing Benard and collaborators’ Topical Fever of exactly a year before in San Francisco. But this revue garnered a better review—even the “blue” side of Benard (misspelled Bennard) gratified via an imagined collaboration on a production of Little Women by Noël Coward, Eugene O’Neill, and Doetvetsky [sic], with Benard and fellow actor Elizabeth Taylor (!) “doing a double-talk love scene” à la O’Neill. The show presumably benefited from having already toured “neighboring army camps and desert resorts” including the Camelback Inn where Benard had worked two years prior.[92]“Opening Due For Musical”; “We, The Players Entertain With Original Music Revue,” Arizona Republic, 10 Apr 1942, 14; “Students Spend Easter Vacation With Parents at … Continue reading

Seven months later Benard was involved with the Cathedral Players, a non-sectarian group formed to refurbish and perform at Bishop Atwood House, built in 1930 as a new wing to the Anglican Trinity Cathedral.[93]1930 – Bishop Atwood House – Phoenix, AZ – Dated Buildings and Cornerstones on Waymarking.com. The occasion was a November 18 performance of vaudeville and one-act plays for military personnel and the general public, which would tour military fields; Benard (misspelled Bernard) was emcee.[94]“Cathedral Players to Present Musical Show Of Circus Life,” Arizona Republic, 05 Apr 1942, 3:2; “Players Plan Program,” Arizona Republic, 18 Nov 1942, 8. In January 1943 Benard would direct the Cathedral Players production of Saroyan’s The Beautiful People and the standard Arsenic and Old Lace for the troupe’s spring season.[95]“Drama Group To Cast Play,” Arizona Republic, 10 Jan 1943, 2. The Republic article states that Benard produced Saroyan’s My Heart’s in the Highlands for Contemporary Theater in San … Continue reading The next month Benard was doing lights for the Phoenix Little Theater in George Washington Slept Here, the George S. Kaufman/Moss Hart comedy that had been adapted for film a few months prior featuring Jack Benny, Ann Sheridan, Hattie McDonald, Lee Patrick, and John Emery, among others. Benard moved onto the boards in the Little Theater’s March 1943 offering of Meet the Wife, a 1920s wife-with-two-husbands comedy with Benard playing husband no. 1. But it was actor Georgia Arthur, playing his wife, who the reviewer called “a three-alarm riot on stage”; Benard was merely described as being “distinguishedly gray around the edges.”[96]“Little Theater’s New Play, ‘Meet The Wife’, Proves Riot,” Arizona Republic, 17 Mar 1943, 2:2.

Coaching Trigger

Benard recalled in his 1950 autobiographical sketch, evidently off by a year, that

1942 [sic] found me headed back to Hollywood and CBS. This time, I really crashed the movies. After coaching everyone on the Republic Pictures lot from John Wayne to Roy Rogers’ horse, Trigger, I went back East.[97]“Playwright Has Jitters As Curtain Time Nears.”

He was registered to vote in Hollywood in both 1944 and 1946; occupation: writer.[98]Benard appears in the Index to Register of Voters, Los Angeles Precinct No. 1602, Los Angeles County, 1944, 1946. Occupations are listed only in the 1944 index. Elsewhere he was identified as having been a writer-director with CBS and “associated with such programs as I Was There, The Whistler and Inner-Sanctum.”[99]“Benard To Teach Class In Acting.” Later Benard would be identified as having been a “former writer-director for the Columbia Broadcasting System” (“Summer Drama Project … Continue reading

Barely mentioned is the fact that during his Hollywood years Benard found time to organize yet another theater project—Vanguard Stage—an actors’ cooperative next door to the Woman’s Club of Hollywood. The Arizona Republic characterized the venture as “a pro-equity [sic] theater training young stars and players.”[100]“Fourth Theater Workshop To Open June 19.” The article appears to refer to Actors’ Equity, the labor union. The little press that Vanguard Stage received began the summer of ’44 with notices in the California Eagle, the African-American weekly, as hosting the Archie Savage Dancers, as screening the short documentary The Negro Soldier (target of an “unofficial boycott” by theater operators), and as producing a summer-long “series of Sunday evenings devoted to the allied arts.”[101]California Eagle: “Archie Savage Dance Group to Appear in a Two Day Fiesta,” 10 Aug, 1944, 13; “‘The Negro Soldier’,” 31 Aug, 1944, 13; “Evening of … Continue reading

That fall Benard was a “ranking member” of the local Young Americans for Roosevelt with musician Artie Shaw and NAACP Junior Council head Ike Adams; actor Olivia de Haviland and boxer Barney Ross were on the national committee.[102]“Young Americans For Roosevelt To Hold a Rally,” California Eagle, 26 Oct 1944, 8. Only Benard and Adams don’t appear in California’s Fourth Report of the Senate Fact-Finding Committee On Un-American Activities: Communist Front Organizations issued in 1948 (California Senate 1948).

Later that fall the “ambitious co-operative group” Vanguard Stage received a rave review for its radio revue It’s in the Air. Radio veteran Johnny Forrest provided the music and lyrics for numbers like “From Minsk to Pinsk” and “Let’s Fight the War in English.” “Paul Charles Bernard [sic], acting as entrepreneur and chief actor managed to keep things going at a rather brisk tempo, and Billy Rose”—assuredly not Fanny Brice’s last husband—“at the piano contributed lively musical interludes and lightened the affair with this sympathetic artistry.”[103]“‘It’s in the Air’ Amusing Series of Songs, Sketches,” Los Angeles Times, 13 Nov 1944, 10. At the time of the staging of It’s in the Air, Fanny Brice’s ex-husband … Continue reading In the spring of ’45 Benard produced Decision, “Edward Chodorov’s play warning against fascism on the home front,” as the Christian Science Monitor described it seven months earlier.[104]“Chodorov’s Anti-Fascist Play As Presented at the Copley,” Christian Science Monitor, 11 Apr 1944, 5. The play had been praised by the New York Amsterdam News as “a welcome relief from the old-school libel which depicted the black man in either a disparagingly low comic light or as equally reprehensible menace.”[105]“‘Decision’ a Hit; Long Run Ahead,” New York Amsterdam News, 26 Feb 1944, 11. The Vanguard Stage production featured Charles Gordon, star of The Vampire’s Ghost (released three weeks later by Benard’s employer Republic Pictures), Helen Bonstelle (niece of theater legend Jessie Bonstelle), and directed by Maurice Clark (who had worked with talents like Earl Robinson and William DuBois in the WPA’s Federal Theatre Project).[106]“‘Decision’ Premiered,” Los Angeles Times, 28 Apr 1945, A6.

At spring’s end, in a Los Angeles Times article complaining about the want of worthy theater in a company town, Vanguard Stage was mentioned as among the exceptions.[107]“Easterner Visions ‘Big’ L.A. Theater,” Los Angeles Times, 17 Jun 1945, B1. Later, that sentiment was amplified by Times drama editor Edwin Schallert’s overview of the 1944–45 season, calling it “hopelessly meager and disappointing” in Burns Mantle’s annual Best Plays roundup. “Only a few times was there any substantial lifting of the depression in quality to be discerned.”

The Vanguard Stage, with a 100-seat house, is designated as a professional co-operative activity operating under the jurisdiction of Actors Equity, and had an ambitious 1945 Summer program including “Beyond the Horizon,” “Goodbye Again,” “Blind Alley,” “Snafu” and “Thunder Rock.” “Decision” was one of their regular season presentations that attained marked distinction. (Mantle 1945, 27)

Yet, Benard’s gripe in San Francisco of “all this rubbish about the theater being dead” in 1940 could have applied to Los Angeles in 1945. Times critics simply did not review (or even notice) most of the productions by a company that its drama editor held in esteem.

That summer Vanguard Stage elected Benard executive director upon its reorganization—a return to its roots as an actors’ cooperative after having tested a different model.[108]“Benard Heads Vanguard,” Variety, 25 Jul 1945, 51; “Vanguard Stage Goes Back to Actors’ Co-op,” Variety, 11 Jul 1945, 50. Benard is not mentioned in the last Vanguard review by the Los Angeles Times, which praises as a “tour de force” Robert Ardrey’s Thunder Rock, an anti-isolationist play written at the height of isolationism, dooming its debut on Broadway two years before Pearl Harbor, despite its star Frances Farmer, its Group Theatre production, and its staging by actor-turned director Elia Kazan.[109]For example, the New York Times, writing in its review that “the logical conclusion to Mr. Audrey’s summons to faith is some sort of counsel for action today. Since no one else is more … Continue reading Despite Benard’s absence the Los Angeles Times review contains this last line, foreshadowing his involvement with the Mattachine: “Philip Cary Jones brought dignity as Dr. Kurtz.”[110]“‘Thunder Rock’ Offered by Vanguard Players,” Los Angeles Times, 18 Sep 1945, 11. It was Jones who may have brought Benard to the Mattachine in 1951, discussed below. And it was Jones who would direct the first production of Chuck Rowland’s Celebration Theatre in 1983.

In the Village

By June 1946 Benard had returned to New York. A Paul Bernard appeared in a “burlesque-ish” English adaptation of Molière’s The Physician in Spite of Himself June 10–12 and 18, presented by Equity Library Theater.[111]“Then They’ll Marry and Live in Czechoslovakia,” Brooklyn Eagle, 09 Jun 1946, 31; “Evans Gets Doctor’s Degree,” Brooklyn Eagle, 14 Jun 1946, 9. It was the play’s “first professional performance in English in New York.”[112]George Freedley, Equity-Library Theatre (Mantle 1946, 450). Founded in ’43, ELT had been a marriage between Actors’ Equity (via Sam Jaffe), which provided talent, and the New York Public Library, which offered its stages—all for free.[113]“Library Theater Proves Worth,” Christian Science Monitor, 12 Jul 1946, 5. Its arrangement with Equity appears to be akin to that of Vanguard Stage as well as the so-called Equity Waiver agreements pioneered in Los Angeles in the early 1970s.[114]“Stage Notes: Guarded Reaction to Equity Waiver,” Los Angeles Times, 07 Nov 1973, E13.

By June 1946 Benard had returned to New York. A Paul Bernard appeared in a “burlesque-ish” English adaptation of Molière’s The Physician in Spite of Himself June 10–12 and 18, presented by Equity Library Theater.[111]“Then They’ll Marry and Live in Czechoslovakia,” Brooklyn Eagle, 09 Jun 1946, 31; “Evans Gets Doctor’s Degree,” Brooklyn Eagle, 14 Jun 1946, 9. It was the play’s “first professional performance in English in New York.”[112]George Freedley, Equity-Library Theatre (Mantle 1946, 450). Founded in ’43, ELT had been a marriage between Actors’ Equity (via Sam Jaffe), which provided talent, and the New York Public Library, which offered its stages—all for free.[113]“Library Theater Proves Worth,” Christian Science Monitor, 12 Jul 1946, 5. Its arrangement with Equity appears to be akin to that of Vanguard Stage as well as the so-called Equity Waiver agreements pioneered in Los Angeles in the early 1970s.[114]“Stage Notes: Guarded Reaction to Equity Waiver,” Los Angeles Times, 07 Nov 1973, E13.

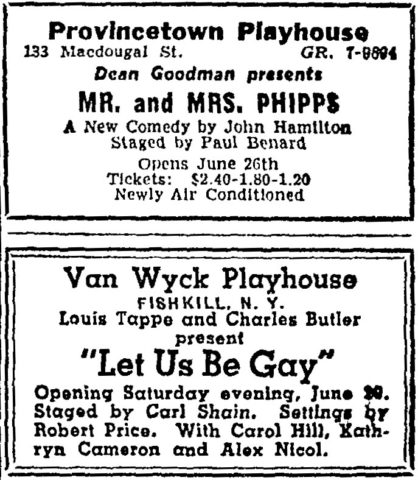

Assuming Paul Bernard was Paul Benard, he was well engaged, premiering another play a week later. With a new slant on summer stock (“experimentation,” the Christian Science Monitor called it[115]“Plays at the Cherry Lane and Provincetown Playhouse,” Christian Science Monitor, 11 Jul 1946, 4.), producer Dean Goodman had launched a series of five relatively new plays at the Provincetown Playhouse in Greenwich Village with the hope that one would get a Broadway bite. Such was not the case with the Paul Benard-directed Mr. and Mrs. Phipps, a romantic comedy by John Hamilton.[116]“Goodman to Offer New Play Tonight,” New York Times, 26 Jun 1946, 20; Off Broadway: In Greenwich Village (Mantle 1947, 494). “There isn’t much to recommend the play,” wrote the Christian Science Monitor.[117]“Plays at the Cherry Lane and Provincetown Playhouse.” Benard fared better with the third of the quintet, It’s Your Move, a musical revue by Jerry Stevens, which Benard co-directed with Don Briody who also acted. Described as “a travesty on publicity and radio advertising,” the musical’s two-week run was held over for a third according to the New York Times.[118]“Maugham to Have 3 Broadway Shows,” New York Times, 24 Jul 1946, 22; “‘Song of Norway’ to Close Sept. 7,” New York Times, 05 Aug 1946, 18. But Variety found the show to be “mild, amateurish,” with music that “is pleasant but somewhat reminiscent and derivative,” and overall having “little commercial appeal.”[119]“Strawhat Reviews: It’s Your Move,” Variety, 31 Jul 1946, 52.

That fall Benard was co-director of a weekly film industry forum to be held on a variety of topics over six weeks at the Barbizon-Plaza Hotel (now the Trump Parc) with each speaker to screen a pertinent film. Film Forum had its headquarters on Washington Square South and the series was limited to one hundred participants on a subscription basis, moderated by Prof. John Gassner, a story editor for Columbia Pictures and drama instructor at the School of Social Research.[120]“Film Forum Will Hold Series of Six Meetings,” Film Daily, 27 Sep 1946, 14. Speakers and topics: Louis de Rochemont/Elia Kazan (untitled), Wallace Ford (The Actor), Willard Van Dyke (The Director), Paul Strand (The Cameraman), Nathaniel Shilkret (The Composer), and a panel of local film critics (The Critic).[121]“Of Local Origin,” New York Times, 04 Oct 1946, 16. The series got off to a rocky start with de Rochemont cancelling due to “production snarls” in the shooting of his Boomerang in Stamford, Conn. Filling in was Jan Read, a Scot who had just obtained a fellowship in New York after working with documentarian Paul Rotha in Europe. (Read would collaborate on the screenplay for Jason and the Argonauts.[122]“A Golden Fleecing By Jason, Argonauts,” Boston Globe, 22 Jun 1963, 4.) Read felt that U.S. exports depicting ordinary life “would counteract a great many misconceptions” via “back streets, paint peeling off walls, shabbily dressed people, etc.” according to Film Daily.[123]“Sees U. S. Prestige Loss Due to Films,” Film Daily, 10 Oct 1946, 11.

In early 1947, Benard partnered with Helen Bonstelle (with whom he’d worked in Vanguard Stage) and Don Briody (his co-director on It’s Your Move) to form

a new producing group called Theatre Project. The venture will consist of a basic company of twelve Equity actors, a non-Equity Laboratory Group and a playwrights department.[124]“Wolfit to Present Third Show Today,” New York Times, 22 Feb 1947, 17. See also “New Producing Outfit,” Variety, 19 Feb 1947, 52.

Whatever the upshot of this venture in New York itself, it was not covered in the New York Times; Benard was merely mentioned as managing director of a summer drama festival in the Poconos.[125]“Along the Straw Hat Theatre Trail,” New York Times, 15 Jun 1947, X3. That turned out to be a Theatre Project of New York production—the East Stroudsburg Drama Festival—which opened July 4 with Thornton Wilder’s Our Town. Other titles in the ten-play season were Wilde’s The Importance of Being Earnest and Maxwell Anderson’s Joan of Lorraine (both directed by Benard) as well as Clifford Odets/Group Theatre’s Golden Boy, and The Dover Road. “At the conclusion of the season the company will make a tour of colleges and universities,” wrote the Times, but there’s no record of such a tour.[126]“Drama Festival Opens Its 6th Presentation,” Morning Call, 08 Aug 1947, 29; “‘Joan of Lorraine’ 7th Performance Opens Today,” Morning Call, 14 Aug 1947, 21. The crew took out time to meet with locals to discuss the next year’s summer program, but it was not repeated.[127]“Monroe County News Briefs,” Morning Call, 27 Aug 1947, 21; “Along the Straw Hat Theatre Trail,” New York Times, 13 Jun 1948, X3.

From Theatre Project to Film Projects: An endeavor by a production company of the latter name was announced as being supervised by Paul Benard in the pages of Popular Photography in its Home Movie Notes section, April 1948 edition. Finding a gap in the educational filmstrip market, Film Projects was to produce a series on Shakespeare for high school and college.[128]The Shakespeare project also was covered in “News Notes,” The Screen Writer, Vol. 3, No. 9 (Feb 1948), 35. In July Benard was directing a documentary with the working title Young Man in a Strawhat, about summer stock theaters, having filmed at more than thirty-five playhouses in New Jersey, Massachusetts, Connecticut, and Long Island. The producer was Marvin Flame Productions, which the next month announced another project with Benard—a weekly series of television shorts titled This Week in New York.[129]“Pic About Strawhats, Variety, 14 Jul 1948, 50; “Movie Will Feature Shots of Playhouses,” Home News (aka Sunday Times), 25 Jun 1948, 21; “Flame Making Series for TV,” Film … Continue reading

Extended Vacation

In his 1950 autobiographical sketch Benard recalled his time in New York, which included

TV films, free-lance radio and finally a two-week vacation which gave me an opportunity to bask in the Phoenix sun. That was in January, 1949. I’m still here.[130]“Playwright Has Jitters As Curtain Time Nears.

Benard’s first job in Phoenix (it also would be his last one there) was teaching a class beginning February 15, 1949 in radio and stage acting at Radio Production Studios. Meanwhile he was “negotiating with NBC for a series of television films for the program, This Week in Focus.”[131]“Benard To Teach Class In Acting.” Ten days later he was advertising for “young men with 16mm experience” in shooting, cutting, editing, and writing for a television project.[132]Classified ad, Arizona Republic, 25 Feb 1949, 35. The venture was revealed on March 9. “Paul Benard, owner of Studio Productions in New York, has moved one-half of his staff to Phoenix where he says he’ll be ready by April 1 to start filming movies for use in television shows,” wrote the Arizona Republic. “Former staff member of KOY in 1941 and 1942, Benard is planning as his first venture in the Valley of the Sun, a series titled This Week In Focus” using local labor. “He also is planning a 30-minute local radio show, Studio Playhouse.”[133]“Tune In,” Arizona Republic, 09 Mar 1949, 21. Neither Studio Productions nor Paul Benard are listed in the Winter-Spring 1946 and May 1948 telephone directories for Manhattan issued by the … Continue reading The radio program was listed as premiering late Monday evening, April 4, on KOY.[134]“Radio Program Guide,” Arizona Republic, 04 Apr 1949, 13. But a notice April 13 claimed otherwise.

Paul Bernard [sic], head of Studio Associates, took to the air at 10:30 p.m. Monday [April 11], KOY, with the first in a series of planned original dramas on Studio Playhouse; little theater of the air stuff.[135]“Tune In,” Arizona Republic, 13 Apr 1949, 10.

The Playhouse aired more or less weekly (albeit moving to Thursdays, then Tuesdays) through mid August.[136]See “Radio Program Guide” listings in Arizona Republic for Thu, 12 May; Tue, 26 Jul; and Tue, 16 Aug 1949. It was preempted on August 23 by a collaboration between Benard’s former employer CBS and “the National Military Establishment”: a Monday-through-Friday series involving all branches of the military “to give the public a complete radio version of the vital information which forms the basis for joint orientation conferences.”[137]“Tune In: CBS To Present Series On Nation’s Defense,” Arizona Republic, 17 Aug 1949, 17; “Radio Program Guide,” Arizona Republic, 23 Aug 1949, 15. The military series was repeated the next week and Studio Playhouse did not return to KOY.[138]See “Radio Program Guide” listings in Arizona Republic for Tue, 30 Aug and Sun, 04 Sep through Sat, 10 Sep 1949. But Paul Benard already had become otherwise engaged.

By the time of Studio Playhouse’s debut Benard had fallen in with a group of nine others that on April 24, 1949 announced the organization of a drama workshop and plans for a civic drama festival.[139]“Drama Workshop Plans Are Laid,” Arizona Republic, 24 Apr 1949, 2:14. Nine days later he’d been named managing director of the project, which planned six major productions to be mounted at the Arizona Musical College during a twelve-week summer season. Among others, Carol Butler of the Phoenix Little Theater would be his assistant and Galen Hays, production assistant at the local Sombrero Theater, was to be technical director. The festival would include a theater arts workshop and radio programs.[140]“Summer Drama Project Planned,” Arizona Republic, 03 May 1949, 21. Three hundred “Phoenicians”—including the mayor as booster—attended a May 12 meeting that introduced the project to the public.[141]“300 Phoenicians Hear Plans For Summer Drama Festival,” Arizona Republic, 13 May 1949, 8.

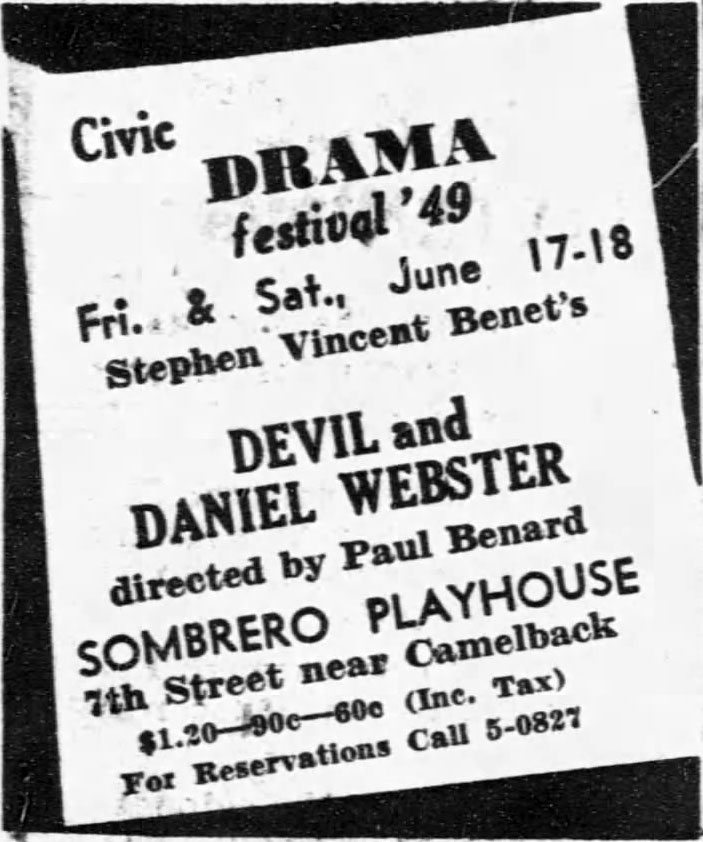

The premiere offering of Civic Drama Festival ’49 was The Devil and Daniel Webster. It wasn’t without speed bumps, however. At least two casting calls were made—the second barely two weeks before showtime for a quarter of the cast—and two more calls were made for props.[142]“Casting For Drama Festival Play Due,” Arizona Republic, 18 May 1949, 3; “Civic Drama Group To Cast For Play,” Arizona Republic, 31 May, 1949, 16; “Civic Drama Festival … Continue reading And the venue was moved from the Arizona Musical College to the Sombrero Playhouse, as announced on June 2.[143]“Drama Festival Site Is Changed,” Arizona Republic, 02 Jun 1949, 2. Despite the glitches, Benard and Butler were augmenting the production, writing a ballad and including early New England folk dances as well as employing a “verse-speaking choir and special background music.”[144]“Aisle Seats,” Arizona Republic, 12 Jun 1949, 2:11. And on the eve of the play’s opening its cast performed a radio adaptation “modeled after CBS’s Columbia workshop—a program which has put the emphasis on the unusual in radio acting,” according to director Benard.[145]“Tune In: Play Cast To Present Preview Of Sombrero Feature On Air,” Arizona Republic, 15 Jun 1949, 20. Such ambition was noted in the play’s review, which observed that “the players showed courage, if not professional polish, in grappling with the elements of a Greek chorus, ballet, square dancing, and such emotions as horror, surprise, anxiety, and exuberance.” The lead was praised, as were the set and lights, but Benard and Butler’s ballad was panned as redundant. “The play was hailed as excellent by the crowd.”[146]“Aisle Seat: Stage Play Is More Genius Than Ham,” Arizona Republic, 19 Jun 1949, 2:11.

The premiere offering of Civic Drama Festival ’49 was The Devil and Daniel Webster. It wasn’t without speed bumps, however. At least two casting calls were made—the second barely two weeks before showtime for a quarter of the cast—and two more calls were made for props.[142]“Casting For Drama Festival Play Due,” Arizona Republic, 18 May 1949, 3; “Civic Drama Group To Cast For Play,” Arizona Republic, 31 May, 1949, 16; “Civic Drama Festival … Continue reading And the venue was moved from the Arizona Musical College to the Sombrero Playhouse, as announced on June 2.[143]“Drama Festival Site Is Changed,” Arizona Republic, 02 Jun 1949, 2. Despite the glitches, Benard and Butler were augmenting the production, writing a ballad and including early New England folk dances as well as employing a “verse-speaking choir and special background music.”[144]“Aisle Seats,” Arizona Republic, 12 Jun 1949, 2:11. And on the eve of the play’s opening its cast performed a radio adaptation “modeled after CBS’s Columbia workshop—a program which has put the emphasis on the unusual in radio acting,” according to director Benard.[145]“Tune In: Play Cast To Present Preview Of Sombrero Feature On Air,” Arizona Republic, 15 Jun 1949, 20. Such ambition was noted in the play’s review, which observed that “the players showed courage, if not professional polish, in grappling with the elements of a Greek chorus, ballet, square dancing, and such emotions as horror, surprise, anxiety, and exuberance.” The lead was praised, as were the set and lights, but Benard and Butler’s ballad was panned as redundant. “The play was hailed as excellent by the crowd.”[146]“Aisle Seat: Stage Play Is More Genius Than Ham,” Arizona Republic, 19 Jun 1949, 2:11.

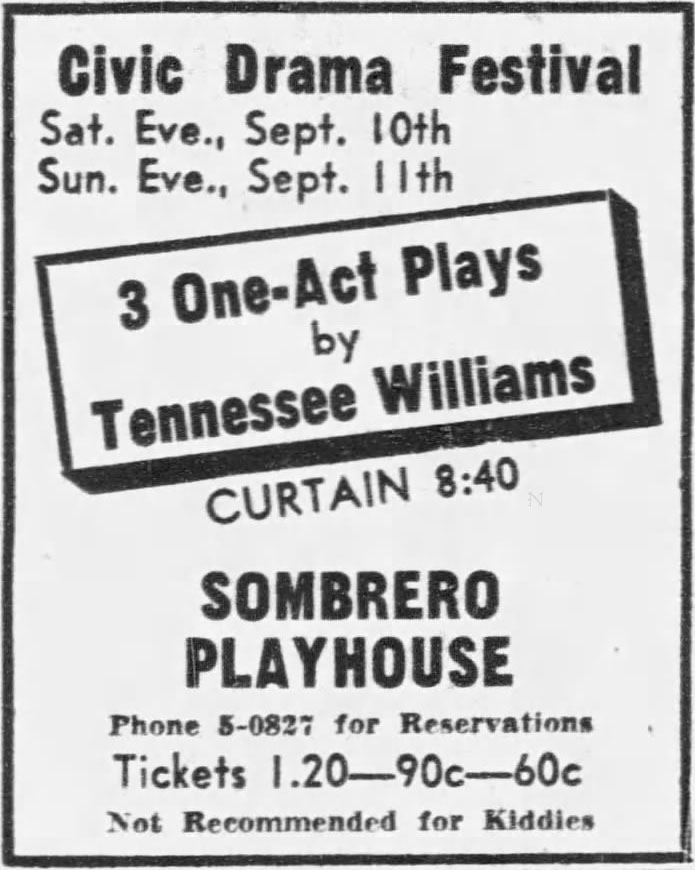

The festival’s four subsequent productions received mostly favorable reviews both by the Republic and by less-than-husky houses: Angel Street (the stateside moniker for Patrick Hamilton’s Gas Light, from which our term gaslighting is taken), Ten Nights in a Bar-Room, George Haight and Alan Scott’s Goodbye Again, and Arthur Miller’s All My Sons. Benard was praised for his directing of each.[147]“Civic Drama: Angel Street Sets Tops At Sombrero,” Arizona Republic, 03 Jul 1949, 9; “Drama Of Past Is Praised At Revival Here,” Arizona Republic, 16 Jul 1949, 7; “Goodbye … Continue reading The festival was extended to feature Damon Runyon and Howard Lindsay’s A Slight Case of Murder, three Tennessee Williams one-acts (the playwright’s Phoenix debut), and Thornton Wilder’s Our Town. Again Benard’s direction of the second and third of these offerings was acclaimed as was his acting the lead character of Joe in Williams’s The Long Goodbye (the first play was given no directing credit).[148]“Whodunit On Schedule Of Civic Drama Festival,” Arizona Republic, 28 Aug 1949, 7; “First Night Audience Hails Tennessee Williams Play Trio,” Arizona Republic, 11 Sep 1949, 10; … Continue reading

The festival’s four subsequent productions received mostly favorable reviews both by the Republic and by less-than-husky houses: Angel Street (the stateside moniker for Patrick Hamilton’s Gas Light, from which our term gaslighting is taken), Ten Nights in a Bar-Room, George Haight and Alan Scott’s Goodbye Again, and Arthur Miller’s All My Sons. Benard was praised for his directing of each.[147]“Civic Drama: Angel Street Sets Tops At Sombrero,” Arizona Republic, 03 Jul 1949, 9; “Drama Of Past Is Praised At Revival Here,” Arizona Republic, 16 Jul 1949, 7; “Goodbye … Continue reading The festival was extended to feature Damon Runyon and Howard Lindsay’s A Slight Case of Murder, three Tennessee Williams one-acts (the playwright’s Phoenix debut), and Thornton Wilder’s Our Town. Again Benard’s direction of the second and third of these offerings was acclaimed as was his acting the lead character of Joe in Williams’s The Long Goodbye (the first play was given no directing credit).[148]“Whodunit On Schedule Of Civic Drama Festival,” Arizona Republic, 28 Aug 1949, 7; “First Night Audience Hails Tennessee Williams Play Trio,” Arizona Republic, 11 Sep 1949, 10; … Continue reading

The festival’s summer theater arts classes were continued in the fall of ’49 under Benard’s direction, including two levels of acting, two levels of stage direction and production, theater research, Shakespearean drama, as well as a curriculum devoted to television and film. The operation was to move from the Sombrero Playhouse to a new location on West Highland with “offices, workshop rooms, and an outdoor rehearsal stage,” as announced on October 2.[149]“Drama Project Quarters Open,”Arizona Republic, 02 Oct 1949, 10. Benard is listed in the 1950 city directory as director of the Civic Drama Festival (Phoenix Arizona ConSurvey City Directory … Continue reading The Festival’s ambitions had ramped up further when on November 11 it announced the acquisition of an under-construction theater on East McDowell including “offices, an art gallery, workshop rooms, an auditorium that will seat between 200 and 250, and a creative arts bookshop.” Exclusive local rights to screen MoMA films also had been obtained.[150]“Drama Group Initiates Art Center Project,” Arizona Republic, 11 Nov 1949, 10. Five days earlier the group had announced two autumn projects—a radio show presenting contestants reading scripts cold and 15-minute TV segments featuring famous playwrights’ works.[151]“Tune In,” Arizona Republic, 06 Nov 1949, 2:12. Meanwhile the group’s onstage aspirations had swelled with a Thanksgiving production of Alice in Wonderland: “a cast of 35, 23 stage settings, special costumes and masks designed especially for the play, and assorted songs, music, and dancing.”[152]“Aisle Seat: Alice Is Picked For Stage Play,” Arizona Republic, 23 Oct 1949, 2:9. With the support of 175, including the cast, it’s little surprise that Alice garnered an enthusiastic Thanksgiving night house of 250+. The Arizona Republic praised all aspects, including actors, organ accompaniment, scenic design, costumes, makeup, and even stagehands. The sets had been enhanced with “splendid realism” by background projections, which were a first for Phoenix, according to Benard who both directed and acted in the production.[153]“Drama Festival Production Of Alice Scores With Crowd,” Arizona Republic, 26 Nov 1949, 28.

The Festival’s new playhouse had its debut January 27, 1950 with a Paul Benard-penned musical adaptation of Ellen Wood’s Victorian novel East Lynne. Despite the inclusion of “songs of the gaslight era” the play was not reviewed by the Arizona Republic.[154]“Drama Festival To Offer Play,” Arizona Republic, 27 Jan 1950, 29. While the Republic called East Lynne “the daddy of all tear-jearkers,” it would provide later scholars much fodder for rumination on notions of female sexuality and agency as well as bourgeois values.[155]See Gail Walker’s The “Sin” of Isabel Vane: East Lynne and Victorian Sexuality in Pat Browne, ed., Heroines of Popular Culture (Bowling Green: Bowling Green State University Popular … Continue reading The show was mentioned in a February 4 survey of local theater.

You may have noticed this funny-looking building near 30th street on McDowell. We did, and curious (nosey), we dropped in. We stayed to see a new pepped-up version of East Lynne and laughed ourselves silly. It met with so much approval they’re going to give it again Feb. 11 and 12. We sought out Paul Benard, manager of the project.

February 10, they’re showing the Italian film, Revenge, starring Anna Magnant, Italy’s leading acrtress, and on the 17th John Steinbeck’s film, The Forgotten Village.

On the 18th and 19th they’re going to stage Clifford Odets’ Waiting for Lefty, and starting on the 26th, in their art gallery, there’ll be an exhibit from the American Artists Galleries in New York. Paintings by Grant Wood, Thomas Benton, and other leading American artists will grace the walls.

As if this wasn’t enough, they have book reviews from time to time and, last, but for our dough, far from least, old-time silent movies borrowed from the Museum of Modern Art. Interesting, we think, to note is the fact that the museum has lent these rare old films to but three other playhouses in the United States […].[156]“Your Reporter Says: Why Not Let Theater Man Write Our Shows?” Arizona Republic, 04 Feb 1950, 10.

Waiting for Lefty was held over for a third performance but obtained no review in the Arizona Republic.[157]Display ad, Arizona Republic, 24 Feb 1950, 33. A casting call went out on February 19 for the Festival’s mid-March staging of The Glass Menagerie, but the local rights were transferred to the Sombrero Playhouse. That venue added an extra night and an “all-star cast” of Robert Walker, John Ireland, Joanne Dru, and Margaret Wycherly.[158]“Festival Books Glass Menagerie,” Arizona Republic, 19 Feb 1950, 2:8; “All-Star Cast Booked In Last Sombrero Play,” Arizona Republic, 12 Mar 1950, 2:7.

Waiting for Lefty was held over for a third performance but obtained no review in the Arizona Republic.[157]Display ad, Arizona Republic, 24 Feb 1950, 33. A casting call went out on February 19 for the Festival’s mid-March staging of The Glass Menagerie, but the local rights were transferred to the Sombrero Playhouse. That venue added an extra night and an “all-star cast” of Robert Walker, John Ireland, Joanne Dru, and Margaret Wycherly.[158]“Festival Books Glass Menagerie,” Arizona Republic, 19 Feb 1950, 2:8; “All-Star Cast Booked In Last Sombrero Play,” Arizona Republic, 12 Mar 1950, 2:7.

The Civic Drama Playhouse season continued with Benard apparently directing: Saroyan’s Hello, Out There, Wilder’s The Happy Journey, Joan of Lorraine (in which Benard both directed and acted), Pinocchio, three Tennessee Williams one-acts (as in ’49 but with one swapped out), and Benard’s own The Frivolous Futtsy.[159]“Two Plays Set by Festival,”Arizona Republic, 08 Mar 1950, 27; “Joan Of Lorraine Pleases Civic Playhouse Audience,”Arizona Republic, 01 Apr 1950, 28; “Pinocchio Play Opens … Continue reading The Futtsy of the latter title ostensibly is a “gentle fairy,” but the Futtsy visiting the Stewart family—“a crotchety old mother and her greedy children”—“gives the family skeletons such a shaking they finally decide it is best to love one another,” as summarized by the Arizona Republic.[160]“Aisle Seat,” Arizona Republic, 28 May 1950, 3:7. The play is the axis around which Benard wrote his biographical sketch quoted above and below, under the title “Playwright Has Jitters As Curtain Time Nears.” He’s remarkably candid about his past indigence and his trepidation in directing his own work—while maintaining tongue in cheek.

[…] I’ve directed 16 plays for the Playhouse to date, other playwrights’ babies. The Frivolous Futtsy is my own baby.

The trembling is back. […] Today I am the author of a new play, my first play. That’s worse than hitch-hiking or sleeping on a park bench or eating in a welfare mission (experiences which I recall with little or no pleasure).

I thought the play was hilarious when I wrote it. The lines were clever, the situation unusual, the commercial potential evident. (A New York agent even optioned it once as a possible vehicle for Beatrice Lillie.) Now I’m not too sure. That Frankenstein taking shape on the Playhouse stage can’t possibly be mine. The lines are dull, the situation’s boring, the scenery would make a good bonfire, the costumes don’t fit, the doors don’t work, the actors can’t act, and there’s one serious problem with the lighting—it’s so bright you can actually see what’s going on up there.

Benard was being somewhat facetious; after all, as he says in his essay, “Hollywood is covering the show as a possibility for pictures.”[161]“Playwright Has Jitters As Curtain Time Nears.” And near-sellout ticket sales prior to opening night caused the Civic Playhouse to slate the run—the last of its season—for three weekends.[162]“Playwright Has Jitters As Curtain Time Nears”; “Comedy At Civic Playhouse Keeps Audience Chuckling,” Arizona Republic, 20 May 1950, 2.

Phoenix Rising

For its summer 1950 schedule of eight productions Benard announced on May 31 that the Civic Playhouse would audition candidates for the entire season rather than cast plays one by one.[163]“Interviews Are Scheduled For Players,” Arizona Republic, 31 May 1950, 27. This new approach might have failed: no productions were mounted in June or July. (Only Benard himself landed a part—a singing role in an unrelated midsummer operetta, Hammerstein et al.’s The New Moon, by an interracial company.[164]“Operetta To Be Given At Bandshell,”Arizona Republic, 23 Jul 1950, 3:5. The operetta was the local debut of the Phoenix Opera Association, a “group of 24 solo voices” that was … Continue reading) The Civic’s theater workshop classes started June 19 (cosponsored by the city’s parks and recreation department), but the Playhouse and its art center were closed during July for air conditioning installation and remodeling. Its “fall season” began August 4.[165]“Fourth Theater Workshop To Open June 19″; “Civic Playhouse Series Will Reopen On Friday,” Arizona Republic, 30 Jul 1950, 2:9. The opener, Lawrence Riley’s Personal Appearance, had been Mae West’s inspiration for her film Go West, Young Man. Wikipedia notes that the play’s initial producer Brock Pemberton favored “escapist fare” like Personal Appearance over agitprop like The Cradle Will Rock and so, after any disappointment of the Civic Playhouse’s non-summer season, Paul Benard may have opted to direct something lighter than, say, Tennessee Williams one-acts.[166]Benard is identified as the director of Personal Appearance in “Comedy Opens New Season At Playhouse,” Arizona Republic, 05 Aug 1950, 4. And with the venue’s reopening Benard had additional ambition. “Beginning with Personal Appearance, the Civic Playhouse will be open every week-end throughout the year,” wrote the Arizona Republic. “One of the few 12-month nonprofessional theaters in the country, the Playhouse is open without charge to every member of the community wishing to appear in plays.”[167]“Civic Playhouse Series Will Reopen On Friday.”

Traditional per-play casting was taken up again as was a vehicle that could have been viewed in light of the nascent Korean War: Lysistrata.[168]“Tryouts Set For Playhouse Productions,” Arizona Republic, 14 Aug 1950, 13. But first Benard and company launched a Chekhov Carnival, featuring The Anniversary, The Boor, and The Evils of Tobacco (a monologue delivered by Benard, a smoker—as borne out by his head shot).[169]“Chekhov Carnival To Bring Short Plays To Footlights,” Arizona Republic, 17 Aug 1950, 16. September was to be rounded out with Gilbert and Sullivan’s The Mikado.[170]“Tryouts Set For Playhouse Productions,” Arizona Republic, 14 Aug 1950, 13.

Lysistrata was staged, but The Mikado was not, likely due to Benard resigning as director of the Civic Playhouse, as reported on October 1, 1950.[171]“New Director At Playhouse,” Arizona Republic, 01 Oct 1950, 3:5. Nevertheless he directed the Aristophanes opus the middle three weekends of September. The play—whose “lines are as timely as when they were written in 411 B.C.”—was adapted by Benard and included a ballet interlude crafted by “New York ballet star” Ruth Sussman, late of Scottsdale,[172]Sussman is identified as having been associated with “New York City’s School of American Ballet,” in Historic Context for Scottsdale’s Development as an Arts Colony & … Continue reading set to Stravinsky’s Rite of Spring.[173]“Classic Greek Drama Readied For Playhouse,” Arizona Republic, 03 Sep 1950, 2:9. The “bold comedy” received only a capsule, noncommittal review, including the ballet sequence, which merely “embellished the show.”[174]“Lysistrata Presented At Playhouse, Arizona Republic, 09 Sep 1950, 4. The Playhouse’s future productions were to be handled by local little theater directors. “First on the list is Louis Knaak, Carnegie Tech graduate and former director of a children’s theater in Maine,” directing Beauty and the Beast.[175]“New Director At Playhouse.”