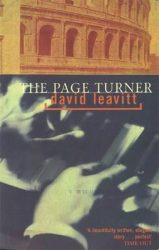

The Page Turner

The Page Turner

by David Leavitt

Published by Houghton Mifflin Company

Published January 1, 1998

Fiction

244 pgs. • Find on Amazon.com

Reviewed by Stephen O. Murray

October 20, 1999.

Although not as bold as his novella “The term paper artist,” David Leavitt’s The Page Turner similarly looks at fame and talent in art along with the sexual needs of aging gay characters and the sexual availability of young adults.

I don’t understand the invidious complaints of many readers who revere The Lost Language of Cranes, because it seems to me that the three main character of Page Turner are not all that different than the gay boy, the abandoned wife, and the dissatisfied husband in Cranes.

The misunderstandings are distinctly Forsterian, especially the blundering woman and the innocent boy at the end. Even more than the Italian part, with Paul’s mother thinking her son’s seducer wants he, the denouement of the book resonates with the catastrophic misunderstandings about others that is the hallmark of E. M. Forster’s work. (There is actually a very stilted and implausible discussion of Maurice.)

Leavitt has always been good at drawing the pain and gaucherie of aging upper middle-class women cast off by their husbands. It seems to me a part that he has been preparing himself for his whole life—at least his whole writing life. But I suspect he soaked up representations of betrayed, abandoned, aging women long before he burst into print in The New Yorker.

Leavitt irritatingly fades away from the sexual connections of Paul and his elders, though he does register who does what to whom in some other relationships. I thought he’d gotten over his squeamishness in “The term-paper artist” (his boldest work, though it doesn’t really delve much into details of sexual behavior, either). I gather that in his newest autobiographical novel, Martin Bauman, or A Sure Thing, Leavitt accepts the widespread criticism of his (many!) failures of erotic candor.

I wonder how much the focus on fame in the novel is Leavitt’s. I was tempted to think that the former prodigy turning 40 was more Leavitt than Paul, but Paul’s obsession with fame echoes the character David Leavitt’s in “Term-Paper Artist.”

For me, the most implausible part of the book is the suddenness and clarity with which Paul recognizes he will not be a great pianist. Could any 18-year-old be so coolly analytical about his talent? For that matter, could the older former-boy-wonder David Leavitt? (I think that there is more of Leavitt in Richard than in Paul, even though Paul shared with Leavitt a Menlo Park upbringing.) Perhaps, but I am skeptical.

20 October 1999, later posted on epinions

©1999, 2016, Stephen O. Murray