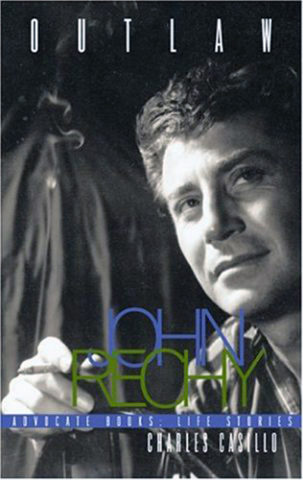

Outlaw: The Lives and Careers of John Rechy

Outlaw: The Lives and Careers of John Rechy

by Charles Casillo

Published by Advocate Books

Published December 1, 2002

History (biography)

256 pgs. • Find on Amazon.com

Reviewed by Stephen O. Murray

December 31, 2007

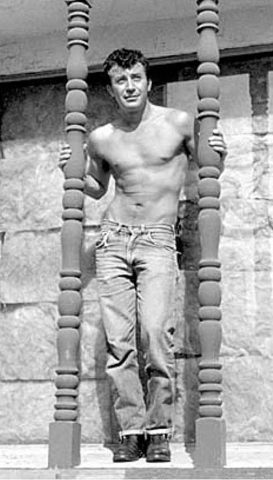

The first challenge in reviewing Charles Casillo’s Outlaw: The Lives and Careers of John Rechy is trying to imagine what someone who had never read John Rechy (2002) would make of the biography. I suspect that the book will have few such readers, even with a cover photo cruising bypassers. The cover is very apt: it and the book each is a portrait of the writer (who was born in 1931 in El Paso) displaying a hard body, the flaunting of which distracts from noticing (around the eyes) that the man eager to be desired and feigning indifference lost the youth he avidly marketed and desperately attempted to retain.

For anyone who has read John Rechy’s books from the 1960s and 1970s, the complex of a need to be desired while hot and showing any desire joined to panic about aging and ceasing to be desirable is familiar. I can’t imagine many readers doubting that City of Night, Numbers, This Day’s Death, and Rushes were highly autobiographical. And The Sexual Outlaw was labeled “nonfiction.” Cassilo shows that what seemed to be less autobiographical, more imagined novels (The Vampires, The Fourth Angel) also transported Rechy and people he’d known into “fiction” with relatively few changes (making adults into teenagers in The Fourth Angel, amping up the luridness in The Vampires).

Rechy was the basis for the never-named hustler in City of Night with a raving need for men to desire his body while denying to himself and anyone else that he was gay and desired sex with men. (The money provides a rationale for sex with men on the part of hustlers not identifying themselves as gay.)

Rechy was also Johnny Rio in Numbers intent on counting coup on the tongues of other men cruising Griffith Park in Los Angeles. Even as a hustler, being paid was more important than the amount of the payment, and Johnny Rio needed reassurance of his desirability and set a target of thirty men going down on him (at which point, he frequently bolted: sexual release was not the point). In ten days of full-time cruising in a very cruisy area, thirty does not seem a high number for a “hot number,” though rapid, anonymous sex in a secluded but officially public space shocked and shocks readers unfamiliar with such venues. The intensity of the desperation for validation was more surprising to me when I first read Numbers.

Being busted by a policeman who could not have seen what he claimed to have seen in the bushes of Griffith Park is central to This Day’s Death, and Casillo turns over reporting on the real trial (and conviction) to Rechy, in a taped interview.

The veneration of a mother seen by her son as a saint back in El Paso in This Day’s Death is very much Rechy’s cult of his own mother. And so on, though Rechy is proud as a peacock about his artful structuring of his experiences in these three novels and is as enamored with his prose artistry as with the image in the mirror he used to kiss every morning…

What is most interesting and new in Casillo’s book is the backstory, the Juan/Johnny of El Paso, the small and pretty boy rejected by his macho father as insufficiently masculine in interests and accomplishments, a “mama’s boy” joto. The intense attachment to his mother is not really a surprise. Given the failure of insight of the fictional narrators, the inability to see that the intensity of that attachment disabled Rechy for intimacy with others is not all that surprising. When the arrest fictionalized This Day’s Death occurred (1966), “at 35 Rechy was still a few years away from accepting his homosexuality. He continued to exist behind a camouflage of games, playing numbers to see how many men would approach him, give him a blow job, want him, then move on quietly. If ever something more than a casual encounter developed, he quickly brought it to a halt.”

Like Jack Kerouac, Rechy returned from his adventures (off the roads rather than on them in Rechy’s case) to stay with his mother, took off without admitting to feeling stifled, returned, took off, returned. And, from the evidence of interviews with Casillo, even now, Rechy does not recognize the pathology of his projections onto his mother and the extent to which his relationship with her precluded intimacy with anyone else. The view of women as either Madonnas or whores is commonplace among Mexican men — who characteristically continue to live at home until wedding their choice of someone to bear and raise for their sons (no, I don’t mean “children,” I mean “sons”) and philander with “loose” women (or willing homosexual males seeking nonhomosexual male sex partners) before and after marrying one of the “good girls.”

The royalties from City of Night enabled Rechy to buy a house for his mother, and although he regularly went off to cruise in New York and Los Angeles, he continued to live with his mother until her death, when he was nearly forty. Rechy was furious at a review of This Day’s Death in the New York Times Book Review titled, “Mother: the monster behind it all.” Although couched in psychoanalytic cant about “flight” from overly possessive mothers into homosexuality, the basic criticism of dishonesty (I’d call it “delusion”) in the very sentimental portrait of the mother-son relationship in This Day’s Death seems to me to be accurate. A third of a century later, Rechy remains exercised about the review (as, with better justification, he is about a vicious but not altogether inaccurate 1963 review of City of Night in The New York Review of Books by Alfred Chester. Casillo presents Rechy’s outraged rejection of the criticism, but the portrait he draws implicitly supports the reviewer’s “defamations.

I’ve already suggested that the most valuable part of this book is filling in the portrait of the vulnerable, probably abused boy before he turned himself into a hard-bodied stud unwilling/unable to love those who desired him but desperately needing to be desired and reassured that his body had not decayed. Casillo considerably over-relies on Rechy, an obviously unreliable witness who has made a career — actually two careers — in mythologizing a stud image. It appears that Casillo made no attempt to access court records or to interview the policemen involved in arresting and testifying against Rechy (the judge died before he received a copy of This Day’s Death that Rechy sent him).

There are interesting perspectives from others who knew Rechy and complimentary remarks carefully recorded from other writers and editor/fan Michael Denneny, so the book is not entirely an exercise in ventriloquism. However, it seems convenient to have someone else collect praise from the most positive reviews and express Rechy’s outrage about the strongest criticisms in others (especially the two already mentioned). Casillo invariably endorses the most positive reviews and deplores any negative ones as misguided and spiteful.

I don’t know if he addresses Rechy in person as “Master,” but Casillo frequently refers to him as an icon and his books as “classics” that have achieved “immortality.” Casillo goes so far as to feature (as a chapter epigram) Rechy’s evaluation that he is “one of the best writers of our time, best of my generation. I certainly rank with Norman Mailer. I certainly outshine Philip Roth. Same with Gore Vidal. I know I rank with them, and that’s my rightful place” high in pantheon of aging writers. Those to whom he compares himself are a set of writers who have pushed various envelopes in subject matter and are exceptionally narcissistic even among writers. All are prolific, continuing to churn out books (Mailer is now dead, but there’s another novel in press), and each has produced multiple best-sellers, but the list of those Rechy considers his more famous inferior is not the most literary or avant-garde a list of 20th-century American writers.

Rechy long rejected identification as “gay” and now rejects categorization as a “gay writer.” The books he has written that do not center on homosexuality have had limited commercial and critical success, while the books about hard-bodied young men who seek validation from gay worshippers continue to sell and to be read. (Indeed, everything else in the biography either points forward or backward to the period chronicled in Rechy’s first three books.)

Self-knowledge was never John Rechy’s forte, and it seems certain he will have learned nothing from the biography with which he has cooperated so extensively that it often seems another mirror for his carefully airbrushed self-image as a great writer with a great body. As for immortality, it’s a bit early for the question to be answered. (A negative answer for the recently deceased Norman Mailer is delivered in the current Smithsonian, BTW).

First published by epinions, 31 December 2007

©2007, 2017, Stephen O. Murray