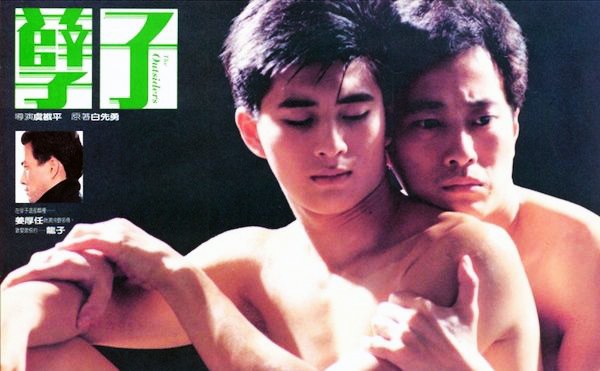

Nie Zi (Outcasts)

Nie Zi (Outcasts)

Directed by Kan Ping Yu

Written by Hsien-Yung Pai

Released August 23, 1986

Drama (foreign—Taiwan)

102 min. • Find on imdb

Review by Stephen O. Murray

November 12, 1993.

My partner, Keelung Hong, says that “The Outcasts” is a better translation of Nieh Tzu/Nie zi, the 1983 novel by Yu Kan-Ping, than the book’s translation as The Crystal Boys. In English the movie has also been titled The Outsiders).

I was disappointed to learn that the array of terms in the subtitles were almost all to glass (bo li). Keelung doesn’t understand why translators have used “crystal.” He says that bo li doesn’t have the connotation of exquisite and valuable, just breakable. Moreover, the book’s title, Nieh Tzu (not Bo Li), is much harsher: nieh means evil; son of sin/evil in the original sense was a son of a concubine, hence a threat to the official family. Such a son is more than bastard; he is family-destroyer.

Dragon twice asks A-Qing to become his “little brother.” This is not just a 19th-century Fujian usage, as some have maintained. BTW, Tokyo Shinjuku “gay bars” (in English) are mentioned by the Captain.

The policeman processing the “crystal boys” after a park raid speculates on whether Mouse is a “zero” or a “one,” sure that Jade is a “zero.” The subtitles have “a yin or a yang”!

Aqing is caught getting fucked at the start of the movie. This results in his being expelled from the military academy and driven out of his father’s house. He also rolls over to be mounted by Dragon twice in the movie.

I don’t remember if the mother is Taiwanese in the novel. Aquing certainly does not go home at the end of the book. The book is also much more park-centered. The gay bars, such as the book’s Cozy Nest, are quickly closed by the police (though new ones spring up), not an ongoing success and place of employment for the boys kicked out by their (Chinese rather than Taiwanese) families like the Blue Angel disco of the movie.

I don’t remember if the mother is Taiwanese in the novel. Aquing certainly does not go home at the end of the book. The book is also much more park-centered. The gay bars, such as the book’s Cozy Nest, are quickly closed by the police (though new ones spring up), not an ongoing success and place of employment for the boys kicked out by their (Chinese rather than Taiwanese) families like the Blue Angel disco of the movie.

It seems to me that the film portrays more tolerant Chinese than the book—or reflects changes? The book begins with Aqing’s expulsion 5 May 1970. The film is set in the late-80s (with the policeman referring to AIDS and a sort of giant Michael Jackson imitation prefiguring his current chicken hawk rep.

“Loneliness needs the anesthetic of love”? Love does not seem to numb Dragon and Ah-Feng (Little Phoenix).

Somehow, the first time I saw the film, that Aqing is going to his father’s house at the end altogether escaped me. I remembered the burning paper money for Mama Yang as the end, not even scooping his ashes into their container. (I didn’t realize that the fire in the dream sequence is burning funerary paper money, either.) Keelung points out that he gathers them up again and keeps a picture of her and of their younger and favored son on the mantle/family shrine. Even such an ogre is not immune to traditional respect for the family’s dead—only for the living!

(At the end of the novel, Aquing rescues a shivering youth from New Park [now 2-28 Peace Park in central Taipei] after hearing Dragon tell of knifing Phoenix ten years earlier on the same spot.)

Although running hysterically away from his father’s house twice and from his mother once, Aqing seems remarkably sane and compassionate for someone treated so badly by his parents. He’s certainly shown as a very depressed child, who loved and tried to save his favored younger brother, who died while the father was out drinking, some time after the mother had been driven away.

The family of necessity (hardly “choice”) is warmer, and Aqing laughs in his surrogate parents’ home. He also cries when he seeks solace from Dragon, so he isn’t affectless. Hurt though he is, he is not a doomed, tragic fag like the figures in ’60s novels and films. He and his compassion survive. In the book, he is an even more positive role model, feeling the responsibility to help others as he has been helped.

Pai Hsien-yung (1937–) was the son of stern (and Mulsim) Kuomintang general Pai Chung-Hi (1893–1966) and until retirement taught at the University of California, Santa Barbara. His most famous book was Taipei People (1971). The Public Television Service of Taiwan aired a 20-part miniseries version of the novel, directed by Tsao Jui-Yuan in 2003. It is not available in the U.S.

©1993, 2016, Stephen O. Murray

from 12 November 1993