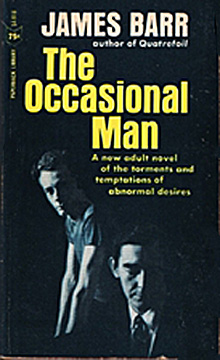

The Occasional Man

The Occasional Man

by James Barr

Published by Paperback Library

Published 1966

Fiction

288 pgs.

Reviewed by “G. D.” (Gene Damon?)

April 8, 1966

James Barr has honored the homosexual fiction genre in the past with two of the finest books available on the subject: a novel, Quatrefoil, and Derricks, a collection of short stories. He is also the author of Game of Fools, a play, published in a limited edition of 2,000 copies by ONE, Inc.

To these achievements, after long years of silence, he has given the lovers of homosexual fiction The Occasional Man. Inexplicably, this is a paperback original and, though Paperback Library has my heartfelt thanks for issuing this book, it is just one more damning commentary on publishing mores that this is not a hardcover novel.

When we meet the hero, David, he is 42 years old, down on his luck but not quite out. At 40, not the easiest of ages to begin his life again, David lost the man who had been his touchstone with life for fifteen years. He has spent the two years in the worst kind of torch carrying—drinking too much, losing his hold on his job and on life in general.

Forced by financial difficulty to move from his Sutton Place apartment to a lower east side dump, he makes an effort to begin again and in doing so meets the titular “occasionals.”

Forced by financial difficulty to move from his Sutton Place apartment to a lower east side dump, he makes an effort to begin again and in doing so meets the titular “occasionals.”

There is golden fuzzy Gus, a clean-looking combination of Nordic and Slavic ancestry, whose simple-minded lusts contain reality, if little humanity. And Hermie, David’s Negro landlord, gentle, fey and a little wistful, who brings David a kind of “marry me, carry me” love, in sharp contrast to the animal horror and glory of Gus. At a drag ball David meets Guilio de Groa, fifty years old and a bull among men. He is an artist at the finest art, that of love, and a much too practiced practitioner.

Most of the book covers David’s adventures with these three men and the ending is satisfactory though perhaps not sufficiently dramatic.

There are flaws in The Occasional Man, both in conception and in the almost masturbatory-fantasy sexual encounters which occupy over three-fourths of the book. The difference between this novel and those designed only to excite sexual emotion is that James Barr can speak graphically of sex without engaging in monotony, and he includes here dozens of those dramatic tendernesses which so marked the major love scene between Philip and Tim in his novel, Quatrefoil. On another level, he has included several polemic speeches on homosexual rights; but these are delivered by David under natural circumstances and do not overly intrude in the narrative.

Mr. Barr seems to have borrowed heavily from several contemporary writers, but he lends his own special magic to the book which comes out as a highly romanticized combination of Baldwin and Little. Few will want to miss this one.

First Published in Tangents 1.7, April 1966

© 2016 by The Tangent Group. All rights reserved.