The Night of the Iguana

The Night of the Iguana

by Tennessee Williams

Published by New Directions

Published 1961

Drama (play)

128 pgs. • Find on Amazon.com

Reviewed by Stephen O. Murray

December 29, 2003

Night of the Iguana was Williams’s last commercial and critical success and is at the top of the second tier of his plays (the top tier: The Glass Menagerie, A Streetcar Named Desire, Cat on a Hot Tin Roof; also in the second tier are Summer and Smoke, Period of Adjustment, Kingdom of Earth, Suddenly Last Summer, Sweet Bird of Youth, The Rose Tattoo).[1]Though I can see aspects of Williams in the poet who writes on, the hedonistic refugee, and the sexual/romantic compulsive characters, there is no overt homosexuality in the play. Night of the Iguana … Continue reading

Most Tennessee Williams plays involve surviving various horrors, especially uncomfortable marital or family relationships, replacing delusions with acceptance of reality (including human fallibility), with protagonists at the end prepared to go on with greater self-knowledge and having supplied the audience (or readers) with some catharsis.

Williams’ work had a reputation for darkness, but his often-vulnerable protagonists almost always turn out to be resilient (bloodied, but unbowed is the apposite cliché, I think) and prepared to try to find happiness within the limitations of their personalities and available options, including relationships.

Williams’ work had a reputation for darkness, but his often-vulnerable protagonists almost always turn out to be resilient (bloodied, but unbowed is the apposite cliché, I think) and prepared to try to find happiness within the limitations of their personalities and available options, including relationships.

Night of the Iguana opens with Shannon, who is conducting a Mexican tour for a group of Texas Bible College women, seeking sanctuary at the Costa Verde Hotel, above the beach of Puerto Barrio. The hotel is run by an earthy woman named Maxine, recently widowed by the death of Shannon’s friend Fred and enjoying the embraces of two of her studly young employees. The tour group, or at least its most vocal harridan, Miss Fellowes, do not want to stay in such a dump, but Shannon has the bus ignition key and reuses to surrender it.

Williams implies that Miss Fellowes’ animus for Shannon derives from jealousy that Charlotte (who has not reached the age of consent—the Texas age of consent, anyway) prefers Shannon’s embraces to Miss Fellowes’. Miss Fellowes wants the tour company to fire Shannon and makes calls to file charges and find out about the Rev. Shannon’s background. (She learns that he was locked out by a congregation after he seduced an underage female and preached seeming atheism). Shannon does not want to compete with Miss Fellowes for Charlotte’s caresses or to have a relationship with Charlotte. He is also trying to break off his relationship with the bottle. And his battle with God is not done, either. He wants to recuperate on friendly, familiar grounds, even if Fred is no longer around.

The first half of the play mostly involves jockeying between Shannon, Maxine, Miss Fellowes, Charlotte, and the bus driver. Just after Shannon’s arrival, Hannah Jelkes, an ethereal, virginal, androgynous woman of indeterminate age appears seeking shelter before the coming storm for herself and her 98-year-old poet grandfather. Maxine does not want any of the women who have showed up staying, though she is willing to provide sanctuary to Shannon. She reluctantly acquiesces.

The last half of the play mostly involves Hannah providing truth therapy to Shannon tied up in a hammock to keep him from harming himself. The first half has quite a lot of conflict; the second half is more akin to the fool and Lear on the moor after the carnage is done. The example of her resiliency, candor about herself, and compassion for others (including the captured iguana under the verandah) get Shannon through the darkest night of a soul that has been tormented with self-loathing through many dark nights and alcohol-numbed days. There is not a conventional romantic happy ending, but the main characters are prepared to make realistic adjustments to their situations and make the best of them.

With elaborate stage directions, this (and other Williams plays) offers a lot to readers, not just lines for actors onstage. I think that Williams had readers as well as actors in mind in writing, though seeing the play performed well provides a more powerful catharsis.

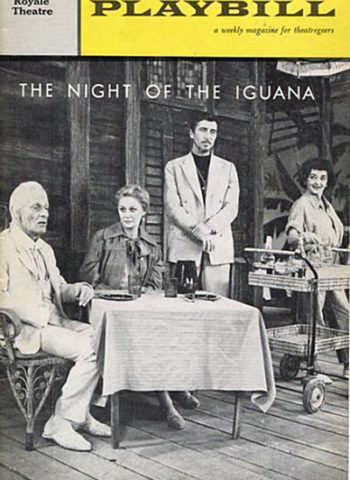

As in (re)reading Suddenly Last Summer, it was hard for me to (re)read Night of the Iguana without hearing the lines inside my mind being in the voices of Ava Gardner (Maxine), Richard Burton (Shannon), and Deborah Kerr (Hannah) from the 1964 John Huston film rendition. (I didn’t even try to imagine any other setting than that of the movie’s Puerto Vallarta beach.) I was trying to imagine the original Broadway cast (in the same order of parts, Bette Davis, Patrick O’Neal, and Margaret Leighton, all of whom I have seen in many movies) but couldn’t. In particular, Gardner looms larger in my memory of the movie than the part of Maxine, even if it was played by an actress not lacking in personality or skill (Davis). Burton was the epitome of self-loathing, and I can’t imagine Patrick O’Neal providing much competition.

As in (re)reading Suddenly Last Summer, it was hard for me to (re)read Night of the Iguana without hearing the lines inside my mind being in the voices of Ava Gardner (Maxine), Richard Burton (Shannon), and Deborah Kerr (Hannah) from the 1964 John Huston film rendition. (I didn’t even try to imagine any other setting than that of the movie’s Puerto Vallarta beach.) I was trying to imagine the original Broadway cast (in the same order of parts, Bette Davis, Patrick O’Neal, and Margaret Leighton, all of whom I have seen in many movies) but couldn’t. In particular, Gardner looms larger in my memory of the movie than the part of Maxine, even if it was played by an actress not lacking in personality or skill (Davis). Burton was the epitome of self-loathing, and I can’t imagine Patrick O’Neal providing much competition.

There are indelible screen performances in most of the film versions of Williams plays, and Night of the Iguana does not seem to have had the censorship problems that mar A Streetcar Named Desire. I think Huston’s film fully realized; it may have improved upon the source play.

Originally published by epinions, 29 December 2003

©2003, 2017, Stephen O. Murray