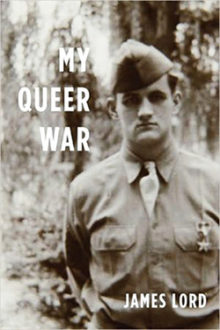

My Queer War

My Queer War

by James Lord

Published by Strauss and Giroux

Published April 27, 2010

History (memoir)

352 pgs. • Find on Amazon.com • WorldCat

Reviewed by Stephen O. Murray

August 6, 2015.

I thought that the first and last parts of James Lord’s My Queer War were overwritten.

Lord, who was born in 1922 and dropped out of Wesleyan University to volunteer for the army (supposedly to the Army Air Corps), waited a long time to write about his experiences in the WWII U.S. Army, but his book, published in 2010, a year after his death, is very timely for showing that U.S. military intelligence engaged in torture back then.

Though Lord had his first homosexual adventures (in Boston and DC) after he had enlisted and been chosen for an ASTP program (in French at Boston College), he was chaste through most of the war, indeed seriously pissing off a superior officer who wanted to have sex with him. Considering his penchant for pissing off superiors in the military hierarchy, starting in basic training in California, he was lucky to survive.

He was puzzled why he and his whole military intelligence group were awarded bronze stars, but it seems to have saved him from more dangerous assignments. (It seems to have been awarded to them for finding and sending up to HQ a set of blueprints of a town that the Germans were fiercely holding.) He was under enemy fire once (by a German tank when he was driving a jeep) but mostly was in danger of being charged for insubordination or transferred into a combat unit by those he annoyed who could transfer him.

After the U.S. Army crossed the Rhine, Francophone MI personnel were superfluous. Lord managed to get into more trouble protesting the mistreatment of “displaced persons” in hellhole camps (not being in uniform, the prisoners were not afforded Geneva Convention protection that was available to Nazis in uniform). He wrote Thomas Mann: “There is now no basic difference between what we are fighting for and what we are fighting against, and it is a hard shock to know it.” The queerness of Lord’s wartime experience was not primarily sexual, but peculiar at pretty much every step, both in assignments and in the conduct of those under whose command he was generally restive.

In Paris, while the war machine was slow to figure out what to do with him next, Lord (“a tourist disguised as a soldier”) was able to meet Pablo Picasso, who drew two portraits of him, and through Picasso, Gertrude Stein, with whom he eventually broke acrimoniously.

In Paris, while the war machine was slow to figure out what to do with him next, Lord (“a tourist disguised as a soldier”) was able to meet Pablo Picasso, who drew two portraits of him, and through Picasso, Gertrude Stein, with whom he eventually broke acrimoniously.

Giacometti and the far lengthier process of sitting for The Giacometti Portrait came after Lord was demobilized and returned to New Jersey (and to Wesleyan). I haven’t read either of his 1950s novels, but I have read three earlier volumes of recollections of relationships with remarkable men and women. He wrote a tome-length biography of Alberto Giacometti, “the one person encountered in my entire lifetime for whom I could feel unequivocal admiration.”

There is a lot of dialogue in the book, even for someone who wrote assiduously in his journals at the long-ago time. And way too many adjectives in the purple-prose opening pages. (I think they thinned out rather than that I got used to them!) Allowances must be made that Lord did not live to make a final edit before the book’s publication (the book includes no information on what editing of the manuscript was done after he died). It does not have the elegant concision of his other memoirs, such as Some Remarkable Men, The Giacometti Portrait, and Six Exceptional Women.

[Rating: 4.2/5]

Pros: macabre experiences

Cons: author died before completing polishing of the manuscript

© 6 August 2015, 2017, Stephen O. Murray