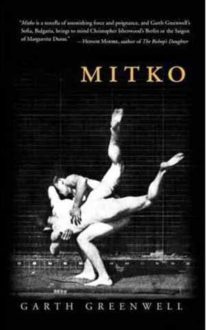

Mitko

Mitko

by Garth Greenwell

Published by Miami University Press

Published June 1, 2011

Fiction

96 pgs. • Find on Amazon.com • WorldCat

Reviewed by Stephen O. Murray

June 13, 2012.

Born in Louisville, Kentucky in 1978, Garth Greenwell is an American poet whose 2010 novella Mitko won the Miami University Press Novella Prize. The prose, though evocative, strikes me as more analytic than “poetic.”

I don’t know why the eastern European city in which the narrator is teaching is not identified at the outset as Sofia, Bulgaria. The author bio says he “lives in Sofia, Bulgaria and teaches at the American College of Sofia,” and one of the blurbs (from Honor Moore) says “Garth Greenwell’s Sofia, Bulgaria, brings to mind Christopher Isherwood’s Berlin or the Saigon of Marguerite Duras.” The latter comparison seems very faint praise to me, the former unearned! The Black Sea port of Varna, where the novella ends, is more vividly sketched, but there is only one Bulgarian character of any import in contrast to those populating Isherwood’s Goodbye to Berlin.

Though the title character, a hustler whom the narrator first encounters in a public toilet and with whom he attempts to pursue a relationship, is individuated, the story is very familiar, recalling Encolpius’s frustrated attempt to bind Giton to his passion in Petronius’s Satyricon (from the time of Nero); the clubfooted physician Philip Carey’s similar frustrated attempt to “save” (and domesticate) Mildred in Of Human Bondage; the smug schoolteacher falling hard for the nightclub chanteuse Lola in The Blue Angel; in more exotic locations, Lawrence Chua’s Gold by the Inch; and, especially (and more recently), Bruce Benderson’s The Romanian (winner of the 2004 Prix de Flore) in which the narrator is obsessed by and unable to domesticate a Romanian street hustler named Romulus (whom the narrator meets in a boy brothel in Budapest and pursues into Romania, and sentimentalizes extravagantly).

The narrators, who are at least somewhat older and more affluent, fantasize partnership and are easily milked and bilked by love objects (/objects of lust) who see sugar daddies (or just regular customers). An essential part of the lover role is to long for more than the beloved can or will provide. An essential role of the beloved (at least in literature, including stage and screen versions) is to elude ownership by their socially superior lover drunk on feelings of benevolence and being the answer to questions the beloved has not asked. And, I think, customers of prostitutes often want to give more (emotion in particular, or call it “intimacy”) as well as get more (than the sex acts paid for).

Like Benderson’s obsession object, Romulus, Greenwell’s Mitko, a 23-year-old trained as a teacher who has done construction work but prefers prostitution, is very focused on material possessions and hyper-aware of brand names. Johnny Raducanu tells Benderson: “For you is fun, a dream and an adventure… But see how you like the party when you stay forever!” Greenwell does not have any native to point this out to him, though he has intimations of it. In retrospect Greenwell’s narrator realizes:

I felt the desire simply to rescue him, though from what exactly and by what means I wasn’t sure. I realized the futility and even danger of this desire and realized too that Mitko had never expressed any desire of his own to be saved.

Even told from the viewpoint of the lover, one can usually see that he disappoints the beloved, too, though the beloved does not articulate as well and seems crass in that disappointment about material acquisitions or the suspension of gifts and/or cash is less sympathetic than disappointment in love.

One cannot expect a lot of detail about the alien society in an 86-page account of surviving love-sickness. Greenwell places the old story in some physical urban locations in Sofia and Varna (and the trip from the former to the latter) and mourns more generally, e.g.:

How can we account for them, time and chance that together strip us of our promise, making of our live almost always less than we imagined or was imagined for us, not maliciously or with any other intent, but simply because the measure of the world’s solicitude is small?

And “Our fantasies are always more vivid than the stuff of life that feeds them, life which always disappoints us until we can embellish it in memory” (and, from the evidence herein, even then!)

Greenwell’s prose is studded with parenthetical asides, not something I would ever criticize. I do think he could have and should have broken up his paragraphs, which run two pages on average.

“How helpless desire is outside its little theater of heat, how ridiculous it becomes the moment it isn’t welcome and reflected, even if that reflection is contrived” (the narrator recognizing his loneliness with Mitko naked in bed beside him).

Greenwell expanded the novella into his first novel, What Belongs to You, published to more acclaim in 2016, three years after repatriating himself to the University of Iowa.

©13 June 2012, Stephen O. Murray