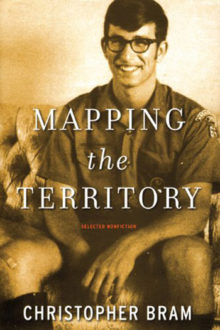

Mapping the Territory:

Mapping the Territory:

Selected Nonfiction

by Christopher Bram

Published by Alyson Books

Published September 1, 2009

Nonfiction / History (essays and memoirs)

300 pgs. • Find on Amazon.com

Reviewed by Stephen O. Murray

April 27, 2010.

If James Whale was “the father of Frankenstein,” the original title of Christopher Bram’s novel on which “Gods and Monsters” was based, Bram must be the father of The Father of Frankenstein. In both paternity cases, the father is younger than the progeny.

I begin my review of Mapping the Territory: Selected Nonfiction by Christopher Bram with that chapter not (only?) because the movie Gods and Monsters is what he is most widely known for but because the chapter “Homage to Mr. Jimmy,” which was originally and afterword to his novel retitled Gods and Monsters, is particularly engaging and informative. I don’t just think that I think this because I am interested in the process of adapting fiction to screens. Bram has interesting things to recollect about trying to interest Ian McKellan in a movie version of his book, Bill Condon’s Oscar-winning adaptation, and the reactions to reworking of his work.

I also especially like the chapter “A Sort of Friendship,” about why Bram and his long-term (30+-year)partner, Draper, support same-sex marriage but don’t feel the urge to marry.

Both those chapters show Bram’s generosity and unwillingness to try to force everyone to believe as he does or condemn them (in the manner of Christianists and of Larry Kramer, whose notorious novel F@ggots, Bram attempted to defend as comedy before being annoyed by one of Kramer’s blatant misrepresentations of others).

Bram’s wry sense of humor is particularly on display in his memoirs “A Body in Books” and “Slow Learners,” which, along with the title essay, recall the extent to which self-exploration proceeded through libraries—that is, reading about gay men. This aided acceptance of gay feelings and to writing about the experiences of gay characters (most not particularly autobiographical ones).

I think that some of Bram’s novels go on too long. His essays show that he can convey a lot in not many pages. The title essay is a particularly good example. It nods to chronology but primarily sorts gay novels typologically (experimentalist, Gothic, fabulist, comic realist, emotional realist, and High Art, the last characterized by cool control and IMHO often overlapping with the experimentalist).

There is a chapter reporting the frustrations many feel in trying to understand the sexuality (and trying to guess how embodied it was) of Henry James, discerning reviews of Edmund White’s brief Proust biography, the memoir of David Brock (a sort of life imitating art instance, the art being Bram’s novel Gossip).

I enjoyed the three chapters on changing life in West Greenwich Village (the first and the last two) and what might seem, especially from its title, the b/tchy “Can Straight Men Still Write?” In it, Bram expresses an impatience I share with Philip Roth, Don DeLillo, Tim O’Brien, and Thomas Pynchon grinding out books that add little or nothing to what they have already done. He wrote the essay in 1999, and it seems even apter now. It is straight White American writers of high repute (critical darlings in fact) whom he targets, not minority group writers, whether their minority is ethnic or sexual. I haven’t gotten to O’Brien novels not focused on Vietnam but stopped reading the other three around the end of the previous millennium. I wish he’d put “White American” in the title even though I’m mindful that it is not all that long a time that Jews have been considered “white.”

There are two chapters that don’t interest me: one about a film Bram, his partner, and their friends made (George and Al) and one about children’s literature (Little Green Buddies), but these may interest others. I don’t think they are less well written than other chapters.

This leaves a chapter about not wanting to read AIDS literature. I have read quite a bit of the literature attempting to address the AIDS holocaust for gay men and don’t much want to read about its marginality (that is to read about people not wanting to read AIDS literature). I did, and the chapter is insightful as well as depressing (at two or more levels).

The collection’s greatest appeal will be for those interested in the relationship of gay literature and gay life (in a pre-Internet age) and/or specifically in the relationship between life (of others) and Bram’s novels.

first published by epinions 27 April 2010

©2010, 2017, Stephen O. Murray

Also see my review of Bram’s survey of post-WWII American gay male literature, Eminent Outlaws.