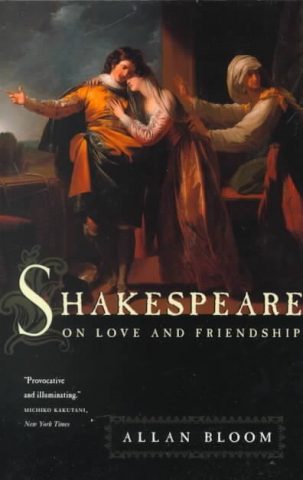

Shakespeare on Love and Friendship

Shakespeare on Love and Friendship

by Allan Bloom

Published by The University of Chicago Press

Published June 7, 2000

Literary Criticism

160 pgs. • Find on Amazon.com

Reviewed by Stephen O. Murray

July 31, 2000.

The University of Chicago Press has published the Shakespeare part of Allan Bloom’s Love and Friendship separately, as Shakespeare on Love and Friendship.

I had to skip the chapter on Measure for Measure, never having seen or read the play, but I found the interpretations of Hal and Falstaff, Romeo and Juliet, Antony and Cleopatra, and the Winter’s Tale intriguing. A little long on plot detail, particularly in the last instance, but what Bloom wrote about Ulysses, Hector, Antony, Falstaff, Mercurtio, Romeo, Friar Laurance, and Prospero is at least tenable. And he is particularly acute about Juliet, Prospero, Octavius, Achilles, and Falstaff. I am not convinced that Shakespeare was so conscious a political theorist as Bloom supposes, systematically surveying different kinds of political communities. (That was Aristotle!) Or illustrating Machiavelli (that was Leo Strauss and his students such as Bloom). Shakespeare certainly portrayed a range of human relationships, though with more recurrent patterns than one would guess from reading Bloom.

In particular, I think that Bloom fails to examine the generally one-way erotics of many close male friends disappointed by being abandoned for wedlock. There is very little representation of what happens after the weddings which are the “happy endings” for some youth, while disasters flow from established marital and quasi-marital relationships in Macbeth, Antony and Cleopatra, Hamlet, Othello, and even Romeo and Juliet, including the deaths of all the title characters in these plays.

Bloom’s notion that Rome’s imperial expansion was over by the time Octavius defeated Antony is very peculiar. Is it that there is no great literature about Trajan than makes Bloom ignore the later imperial growth? There was no “end of politics” or shortage of enemies, internal or external, for later emperors to contend against.

As an introduction to Bloom’s values and ways of thinking about canonical texts, this volume is far superior to Saul Bellow’s fictionalized memoir, Ravelstein. Shakespeare’s Politics provides even better an introduction.

There is no indication in Shakespeare that eroticism is sinful, although there is plenty of indication that it reflects an incoherence and dividedness in human nature itself. (23)

Similarly, Bloom calls attention to Shakespeare’s “dislike of moralism” (36 and re: Hostpur) and sees in Antony and Cleopatra “the issue is not between chastity and sinning but between politics and love” (33).

Bloom’s claim that Shakespeare had a “taste for women” (39) ignores much, not least the sonnets, and violates Bloom’s own strictures against reading autobiography into Shakespeare’s work.

posted on epinions 31 July 2000

©2000,2016, Stephen O. Murray