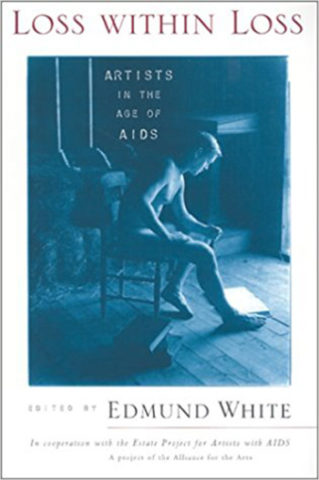

Loss Within Loss: Artists in the Age of AIDS

Loss Within Loss: Artists in the Age of AIDS

edited by Edmund White and The Estate Project for Artists With AIDS

Published by The University of Wisconsin Press

Published January 18, 2001

History (biography)

312 pgs. • Find on Amazon.com

Reviewed by Stephen O. Murray

March 1, 2003

Hardly anyone wants to read about AIDS. (This is as true in 2017 as it was when this review was written in 2003!) Many people have written about it, but for the most part books focused on AIDS have not sold. The relative success of the collection of memoirs Edmund White edited in Loss Within Loss: Artists in the Age of AIDS is primarily about artists, secondarily about their art, and not mired in the symptomology of rapid decay.

Having acquired the book at a meeting, I planned to dip into the volume to read about several writers felled by HIV but found the quality and intensity of the pieces by or about writers whose work I know so high that I kept reading (though skipping around) to read chapters by or about artists (a composer, some film-makers, photographers, painters, two architects, a sculptor/furniture-maker, a choreographer, and a puppeteer) of whom I had not previously heard. Some of these chapters turned out to be even more powerful than those about those who attained some reputation before being cut down.

Although everyone written about was white and male and lived at least part of his life in New York City, the lives recalled are very heterogeneous, ranging from the extreme privilege to which James Merrill was born, to the hard-scrabble existence of David Wojinarowicz, and from the recognition Merill attained in his three score and ten years to the nonrecognition of many of the men who died before the age of 40.

Writing about someone who worked in a fragile medium (but not one as evanescent as choreography or puppeteering), Johnathan Weinberg challenges the romantic myth of artists dying young and/or unrecognized:

“Art is long, life is short,” or so we are told. Art bestows immortality on the artist. But what if the artist never becomes famous and death comes before his or her art ever becomes known? Another cliché has it that works of art only become really valuable after their creator dies. It is the story of van Gogh’s troubled life, and the astronomical auction prices of his canvases, that fuel this myth. In truth, it is rare for an artist to achieve posthumous fame after a career in obscurity. Even van Gogh’s life does not quite fit the myth, since before he died his work was already well known to the French avant-garde, and his brother was an influential art dealer. Indeed, how could it be otherwise? How can works of art be known if there is no one to care for them and put them before the public? These are tasks that initially fall on the artist. If lack of fame hinders an artist’s life, creating poverty and depriving him of the time and space to make art, it can be equally devastating to the works themselves after the artist’s death.

Andrew Solomon takes aim at the dying young romance:

There is always the Mozart story out there: somebody died young with a whole lifetime already achieved. Then there are the rest: those who slowly, over perhaps three score years and ten, built up bodies of work informed by experience… If he’d died in his thirties, there would for all intents and purposes be no Beethoven.

The contributors do not make extravagant claims for the genius of the friends they mourn. Some express ambivalence for the work, and some express ambivalence for the dead artists as well as for their work. The most irreverent (and, in my opinion, best), “Who turned out the limelight? The tragi-comedy of Mark Morrisroe” by Ramsey McPhillips, borders on savagery. Its subject was more than a little bit of a monster. That he imagined himself the son of the Boston Strangler is far from the most outrageous part of how he presented himself.

Some strong pieces are more about their authors’ feelings than about the dead artists being portrayed (Alexander Chee’s “After Peter,” Randall Kenan’s “Where R U, John Crussell,” and Craig Lucas’s “Fucked”). J. D. McClatchy’s chapter on the two best-known writers essayed in the volume, James Merrill and Paul Monette, both of whom were his friends but did not like each other, makes his complex feelings clear without eclipsing the ostensible subjects (in contrast to Herbert Muschamp’s “Self-portrait with rivals,” which at least has a honest title signally its author’s self-absorbed).

Balance between writing about the dead artist and the writer’s feelings is also attained by two writers about whose work I am generally dubious (Brad Gooch writing about documentary film-maker Howard Brookner; Felice Picano writing about novelist Robert Ferro).

I also found what Sarah Schulman wrote about writers Stan Leventhal and David Feinberg acute. Allan Gurganus pays handsome tribute to James Merrill. And there are moving and beautifully constructed tributes to less well-known artists. I would single out William Berger’s to composer Chris DeBlasio, actor/writer Keith McDermott’s to collage-maker and writer Joe Brainard, Robert Rosenblum to sculptor Scott Burton, Alex Chee’s to painter Peter Kelloran, Randall Kenan’s to playwright John C. Russell, and (again) Ramsey McPhillips’s Mark Morrisroe.

Edmund White provides an elegiac introduction, but one that fails to clarify what “in cooperation with the Estate Project for Artists with AIDS” means (and Maya Angelou’s closing chapter titled “Estate Project for Artists with AIDS” does not add much in the way of information about the project and its relation to the book, though it has an affecting tribute to one of those felled by HIV to whom she was close).

There is a lot of competitiveness among artists on display in this volume, as well as recollections of extraordinary generosity on the part of some. One can see something about how inbred the Manhattan cultural scenes of the 1970s and ’80s were (though I doubt much has changed in that regard). Though many of the contributors, the subjects, and the editor traveled widely, the book seems to me excessively New York-centered (though there are a few subjects who never lived there), not least in the obsession of notice being taken (reviews, obituaries) by the New York Times. (This book was not reviewed there, incidentally, though White writes for it with some regularity.) New York hype is so insistent that even a book published in the center of the continent (Madison, Wisconsin) hardly registers the possibility of creativity outside New York City, or that creative gay men who had no connection to New York have died of AIDS.

Given that the mortality rate among gay black writers has been even higher than the numbingly high mortality rate among white gay writers, it is hard to defend or explain that all the subjects (except for part of a page in Angelou’s brief closing essay) are white (three of the 22 authors are not). I don’t want to close with complaints about what is not in the book. What is included is sometimes hilarious, sometimes macabre, often searing, often moving, and both more informative and more entertaining than I expected when I bought the book.

first published by epinions, 1 March 2003

©2003, 2017, Stephen O. Murray