Life Drawing

Life Drawing

by Michael Grumley

Published by Grove Weidenfeld

Published September 1991

Fiction

156 pgs. • Find on Amazon.com

Reviewed by Stephen O. Murray

January 1, 1994.

Reading Michael Grumley’s Life Drawing (published in 1991, three years after the author’s death) makes the sense of loss about truncated oeuvres even more acute.

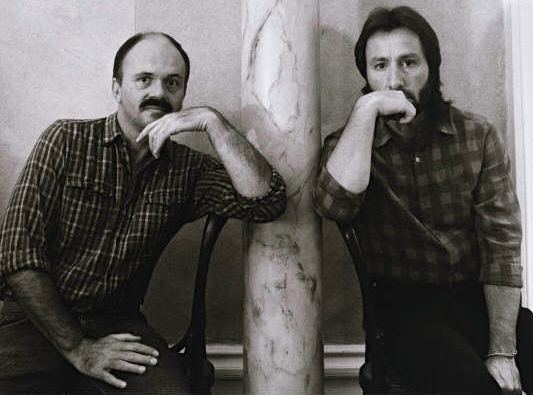

The foreword (by HIV+ Edmund White) and afterword (by dead-of-AIDS George Stambolian) focus on the loss of both Grumley and Robert Ferro. The dust cover includes a picture of both (shown below) and a blurb from Melvin Dixon (also dead-of-AIDS). Such a catastrophic swath of destruction!

It took me a while to accept Grumley’s cadences, but not the bildung. (Homo-)sex can transform the feeling that we can’t feel—or want.

Even at the end, Mickey credits James (the first love who he carelessly discarded) with more wisdom and conscious control (not just sophistication) than is remotely likely. Perhaps James would have handled “it” (the guilty infidelity) had Mickey not fled.

Mickey is awfully hard on himself! Aren’t paradises always lost—except to the reconstructions of memory? This applies to the loving family in Iowa (including Mickey’s gay-accepting older brother, Franklin), exciting to the young Mickey New Orleans as well as to his relationship with James.

I don’t understand how Edmund White could introduce this text as evidence that the sex of beautiful men (a category I am not convinced Grumley was in) “isn’t hungry, grateful, greedy, or choked with emotion” (vii). Except for “greedy,” it seems to me that Mickey has sex that is all of these.

It also seems to me that if sex is his vocation, he failed (or gave it up) and became what White saw Grumley as: detached and overly certain in his sense of his own limits.

©1994, 2016, Stephen O. Murray

1 January 1994