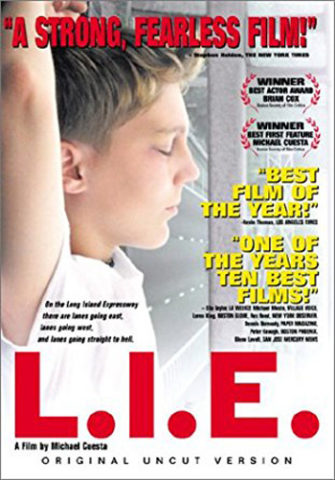

L.I.E.

L.I.E.

Directed by Paul Dano

Written by Stephen M. Ryder, Michael Cuesta, and Gerald Cuesta

Released January 20, 2001

Drama

97 min.

Review by Stephen O. Murray

October 12, 2001.

Most everyone who has written about L.I.E. has noted resemblances to American Beauty. Somewhat oddly, some of the same people have objected to the ending of L.I.E. as arbitrary, though the ending is one of the things that seems to come directly out of American Beauty.

It seems to me that the first half (or so) of L.I.E. derives more from My Own Private Idaho than from American Beauty, though Brian Cox’s performance as Big John is so compelling that it tends to obliterate remembering the first half after the film is all over.

As in My Own Private Idaho, L.I.E. has a gang of alienated adolescent males with a special relationship between two of them. Then 17-year-old Paul Dano, as Howie, is in love with or at least intrigued by then 16-year-old Billy Kay as Gary in L.I.E. as River Phoenix was by Keanu Reeves in Idaho. When they are around the fire, Howie does not blurt out his love (sexual interest). Howie only says that he is a virgin. Gary responds by running through various attractive features of Howie—whether to reassure him, to encourage a sexual advance, or, perhaps, anticipating pimping Howie when they run away to L.A.

As in My Own Private Idaho, L.I.E. has a gang of alienated adolescent males with a special relationship between two of them. Then 17-year-old Paul Dano, as Howie, is in love with or at least intrigued by then 16-year-old Billy Kay as Gary in L.I.E. as River Phoenix was by Keanu Reeves in Idaho. When they are around the fire, Howie does not blurt out his love (sexual interest). Howie only says that he is a virgin. Gary responds by running through various attractive features of Howie—whether to reassure him, to encourage a sexual advance, or, perhaps, anticipating pimping Howie when they run away to L.A.

The next morning Gary sizes up Howie’s body and tells him he has nothing to be ashamed of. This further confuses Howie, inculcating new concerns (at least so it seems: are there really any adolescents who are completely confident about their bodies?). Howie looks with evident longing at Gary, and their gangmates assume that Gary and Howie are sexually involved with each other.

Gary is planning to run away from home and has convinced Howie to accompany him in crossing the country. Gary is also the impetus to the gang of four robbing Big John while the latter is celebrating his birthday. Gary steals a pair of pistols, and Howie is nearly nabbed escaping. Big John is left holding a back pocket of Howie’s jeans: it comes off very neatly, I must say. This piece of denim is immediately fetishized by the pederastic ex-marine, who is determined to find who has ripped him off—and to have his way with him. (Let me digress to say that I find it hard to believe that there is even a slight scent of the boy on the third layer of fabric away from his skin.)

Then we learn that Big John knows Gary, and Gary gives up Howie (as having stolen the pistols that Gary stole) to him.

The second half of the movie shows the hunter’s heart being captured by the game’s—or the hunter being disarmed. Howie is ambivalent about being the object of desire: a little scared, more than a little excited. And Big John is torn between his desire for Howie’s body and taking the place of his parents. Howie’s mother died in an accident at a Long Island Expressway exit, and his father [Bruce Altman] is far more focused on playing stud and bimbo in a midlife crisis from which the wife has been conveniently removed than he is in raising his son. And then he is arrested and jailed for his corrupt contracting business.

I find the first half of the film more interesting, trying to figure out Gary’s game. Americans, including the motion picture raters, are preoccupied with “child molestation”—though none happens in the film, and Howie is not a child (though he is certainly not an adult, either). Any dispassionate analysis would conclude that Howie is exploited by his age-mate Gary and is not exploited by the adult “sexual predator” Big John. (Similarly, as far as the more sexually experienced preying on the less sexually experienced, Gary is Howie’s age mate but exploiting his greater experience with seductiveness.)

Big John has a clear prurient interest in Howie, but, like the Kevin Spacey character in American Beauty, he stops short after realizing that the youngster’s apparent knowingness is counterfeit. (And, as in American Beauty, another character acts on false assumptions about what the pederastic adult is doing.) Perhaps even more unsettling to many viewers is the question of whether Big John is a better father than is Howie’s biological father. The latter mostly ignores his son and gives him a black eye when he does notice him.

Big John insists that Howie visit his father in prison. Howie warns his father never to hit him again and has the new-found confidence to tell his father that he may be replaced. It seems to me that Howie wants Big John to demonstrate the skill at fellatio Big John claims (and advertises with those initials on his car license plate) and is disappointed.

Big John insists that Howie visit his father in prison. Howie warns his father never to hit him again and has the new-found confidence to tell his father that he may be replaced. It seems to me that Howie wants Big John to demonstrate the skill at fellatio Big John claims (and advertises with those initials on his car license plate) and is disappointed.

From my (distant!) memory of being 16-17, I think that being done by a grizzled adult would be more a relief than a trauma, though I am very well aware that contemporary American culture holds that any sexual contact between adult males and adolescent males is “abuse” (while taking sexual contact between adult females and adolescent males less seriously, and expecting large differences in age and sexual experience between males and female to be common). Moreover, I am puzzled why skill would be needed for servicing “young, dumb, and full-of-cum” males.

It is interesting to me that there is relatively little concern about a 50ish man and young males of 15-16 in Our Lady of the Assassins in contrast to the NC-17 bar placed on L.I.E. Is it because the males in Lady are brown while those in L.I.E. are white? Or is it because the life expectancy of the 16-year-olds in Lady is very short? That is, they are old enough to kill and be killed, so are perhaps old enough to consent to sex with an older man? The Colombian adolescents have sex with Fernando, whereas B.J. does nothing more than shave and ogle Howie. (And the remake of Lolita in which the girl is supposed to be twelve got an R-rating…)

I think that L.I.E. is an interesting film that raises some questions that many Americans don’t want to consider (the certainty that adolescent males must be protected from sexual relationships with adults is right in there with the belief that whoever allies with the U.S. at any given point is on the side of “freedom,” as the Taliban used to be when fighting “the Evil Empire” of the Soviet Union…) and that I have no particular enthusiasm for addressing, either. (Do I need to stipulate that I’m not attracted either to Paul Franklin Dano or to Brian Cox?)

It may be that the reaction (the NC-17 rating and the horrified New Yorker review which condemns the film for not making Big John a monster, as we are supposed to view adults interested—sexually and otherwise—in adolescents) is more interesting than the less than completely coherent film. Romeo Tirone’s cinemaphotography in L.I.E. is not as fancy as Conrad Hall’s in American Beauty, and the actors are less well-known than Kevin Spacey and Annette Benning, though the L.I.E. ensemble cast turn in performances as good as those in American Beauty. I don’t think the ending in L.I.E. is any more arbitrary than that in American Beauty. But I like the plastic bag floating up in cross-winds more than the three repetitions of Howie balanced on the railing of an L.I.E. overpass. The opening one is OK, but the east/west/straight to hell characterization of the Long Island Expressway is never connected to what happens in Dix Hills among these confused adolescents and weak adults, though I guess one could argue that Howie remains on the ledge between childhood and adulthood with a still unsettled sexual orientation.

Dano, by the way, has gone on to appear in movies such as There Will Be Blood and Love and Mercy. Billy Kay’s subsequent career has been mostly guest appearances on tv dramas.

published by epinions, 12 October 2001

©2001,2016, Stephen O. Murray