Like recent books on London and Chicago, When Brooklyn was Queer is more experience-near than academic writings about lesbian, gay, and transgender urban experience have been. It overs approximately the same time period as the Chicago one, 1855-1955. Although for me too much of the book is about a few poets (Walt Whitman, Hart Crane, Marianne Moore), along with dancer Mabel Hampton and novelist Carson McCullers, Ryan provides commendable attention to the depredations of Robert Moses under the guise of “urban planning” (certainly NOT renewal, as was claimed in the 1950s and 60s). His text approaches gender parity.

I suspect that a map (or maps!) would have been of assistance even to Broolynite readers, and would have been very helpful to me. I also find the referencing very frustrating: I don’t like endnotes, and especially dislike endnotes that require one to remember what chapter one is reading (rather than including the page numbers where the notes originate at the top of the page of notes). And there are no specific page references for quotations. Moreover, some of the notes cannot possibly be right (e.g. note 82 on the last chapter).

Misuse of “decimation” and using “disinterested” for “uninterested” are pet peeves of mine, of which Ryan runs afoul.

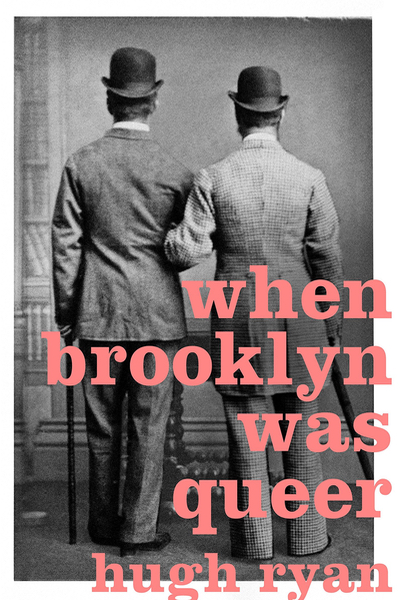

(Postdlf photo of Brooklyn Bridge, looking toward Brooklyn)

And I find the use of “queer” as a catchall offensive. Gender nonconformity (from expected roles for one’s sex) is currently fashionable, but is NOT inclusive. It leaves out people now and then who consider themselves “normal,” the antonym of “queer.” For one, Walt Whitman clearly did not consider himself “queer,” nor did other masculinity-venerating people. (Other than in some senses Whitman, there do not seem to have been masculinist ideologues in the US comparable to John Addington Symonds and Edmund Carpenter [and the author of Maurice, who was inspired by Carpenter] in England or the Der Eigene circle in Germany [building on Johann WIncklemann]). There were (and are) a lot of people who reject their designation by others as “queer,” and I very much wonder if there is or ever has been a gay/lesbian/bisexua/transgender “community,” though some people have felt themselves to be part of a “lesbian community” or a “gay community. Ryan discusses views of a population of those regarded by their sexual partners as “real men” (not homosexual), but there is little available (not only in this book) about the sexual subjectivity of those masculine-appearing men who were “serviced” “homosexuals.”

The book is primarily secondary research (I guess the stuff from Thomas Painter’s letters to Alfred Kinsey constitute “primary research”), which is a description, not a criticism. The book is obviously episodic, but does move chronologically through mostly well-written accounts of particular individuals and meeting-places within a changing Brooklyn — with careful consideration of government policies aimed at keeping “those kind of people” invisible and other ones not targeting gay/lesbian/transgendered lives but for which the harm was “collateral damage” and at the racial animus of many urban New York policies.

(BTW, even at the height of “the pansy craze,” Brooklyn was never predominantly inhabited by “queer” people. Some building and blocks had many gay or lesbian residents, but none exclusively so).

©2019, Stephen O. Murray