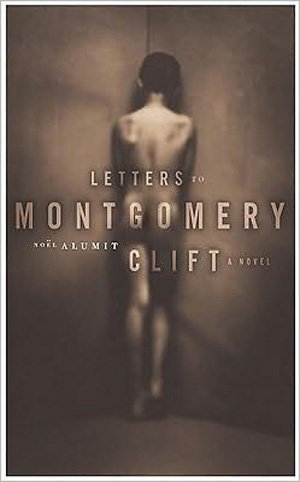

Letters to Montgomery Clift

Letters to Montgomery Clift

by Noël Alumit

Published by MacMurray & Beck

Published February 1, 2002

Fiction

244 pgs. • Find on Amazon.com

Reviewed by Stephen O. Murray

July 24, 2002.

Like the narrator of his first novel, Noël Alumit was born in 1968 in the Philippines and graduated from USC. I fervently hope that the main story of Letters to Montgomery Clift is not autobiographical and that the life story of the writer and of his character only share the same locales.

When Lady Bracknell proclaims that to lose both one’s parents suggests carelessness, she was ensconced in a society in which dissidents were not “disappeared.” The very first two lines of the first of Bong Bong Luwad’s letters to Montgomery Clift are “I want one thing only. Please bring my mama back to me, safe, with no more bruises.” Bong’s father was a journalist who criticized the Marcos regime. Bong was under the bed when policemen came and beat his parents and took his father away.

His mother managed to get Bong Bong on a plane to America, where her sister was, his Aunt Yuma. His mother promised to follow, but no word from her arrived in Los Angeles. Bong’s losses continued. His one friend moved to a better neighborhood. The kindly, studly neighbor moved to D.C. And then Aunt Yuma disappeared. Bong was placed in a series of foster homes and lost his name, becoming “Bob.”

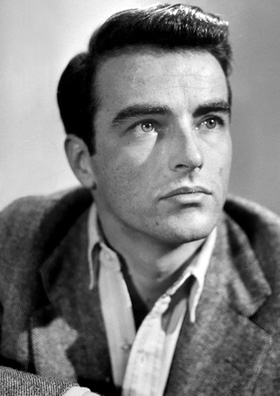

Practically the only thing he did not lose was his hallucinatory special relationship with Montgomery Clift. Although Clift died three years before Bong Bong was born, Bong Bong bonded to the character Clift played in The Search: a soldier who “finds and cares for a small boy whose mother was taken away by bad people. He takes the boy home. He gives him candy. He buys him shoes. He teaches him English. He keeps him safe. He guards the boy until his mama comes.”

The notion of writing out prayers came from Aunt Yuna, who told him writing was better because “prayers just go from your head into thin air.” Moreover, she advised,

Dead relatives are the best people to ask things. Better than God. Dead relatives already know you and you know them. People will do things for people they know. God knows everyone and treats everyone the same. I want to ask a favor from someone who will give better treatment.

The patron-client relationship so central to Filipino society was part of Bong Bong’s cultural heritage, but he did not know who the saints were, who his ancestors were. Hoping that his parents were alive, he could not pray to them, and he fixated on a dead but once-handsome movie star he felt he knew.

Each chapter begins with one of the letters, though most of the novel is recollections of the times at which the letters were written, and, therefore, not in the childish present tense voice of the letters.

The shock of his parents having been taken away is so great that his culture shock is not particularly severe. He is isolated, going through the motions of being a good student and trying to cope with a succession of unreliable caregivers. Eventually, he becomes the ward of a Filipino couple unable to make more children of their own and becomes very close to Amanda, a daughter they find unsatisfactory (being expelled from boarding school, wanting to be an actress, etc.). Amanda idolizes Marilyn Monroe, so the two can watch The Misfits and Bob takes Montgomery Clift trying to protect Marilyn Monroe here as a model. All four are significantly out of touch with reality, though Amanda surprisingly turns out to be the most realistic of the dreamers. She realizes that she may fail but considers failing better than not trying.

The shock of his parents having been taken away is so great that his culture shock is not particularly severe. He is isolated, going through the motions of being a good student and trying to cope with a succession of unreliable caregivers. Eventually, he becomes the ward of a Filipino couple unable to make more children of their own and becomes very close to Amanda, a daughter they find unsatisfactory (being expelled from boarding school, wanting to be an actress, etc.). Amanda idolizes Marilyn Monroe, so the two can watch The Misfits and Bob takes Montgomery Clift trying to protect Marilyn Monroe here as a model. All four are significantly out of touch with reality, though Amanda surprisingly turns out to be the most realistic of the dreamers. She realizes that she may fail but considers failing better than not trying.

It is obvious to Amanda that her foster brother is gay before he knows it. Mr. Clift, that surrogate father, metamorphoses into Monty, the ideal lover.

“I ached for some of the guys at school, guys in magazines, guys on TV. I knew I couldn’t do anything, say anything…. I took comfort in the life of Montgomery Clift. I knew he hid his sexuality, too. I think that is one of the reasons why I liked seeing Monty in his movies: he was hiding. He was visible to millions of people, but he hid…. I understood the importance of hiding.”

A certain amount of self destructiveness went with such a model and the painfulness of the story is not only in the torture of Marcos’s opponents. After Marcos’s fall, information about the latter comes out, and Bob psyche becomes more frayed, but I don’t want to give away either the plot or the character development. The novice novelist handles the latter more convincingly than the former, though I suppose that someone so deeply seized by particular Hollywood hallucinations as Bong/Bob probably deserves a Hollywood ending.

Evaluations

Alumit creates a number of vivid characters, including Aunt Yuma, Dr. Chapman, Amanda and Bong/Bob’s visions of J and of Montgomery Clift. However, the other male characters (Mr. Arangan, Dr. Chapman, Logan, Robert) are fairly one-dimensional and Mrs. Arangan, Mrs. Billaruz, and Mrs. Baker maybe one-and-a half dimensioned.

I don’t know why Alumit chose to give the son of an anti-Marcos martyr the name that Marcos’s playboy son was called. I kept expecting some reference to Bong Bong Marcos, but Bong Bong Luwat only refers to the king and queen of the plunderers of the Philippines, Ferdinand and Imelda. (I was also curious what Bong/Bob would make of Red River but didn’t find out.)

Although there are a lot of issues (torture of political prisoners, complicity with dictators’ money-laundering, exile, sexualities), the book does not seem didactic in the least. Bong Bong has or develops some of the compassion for others, including those responsible for his own sufferings, of “Miss Lonelyhearts.”

The horrors swallow up Bong Bong far more quickly than those in Sri Lanka and Laos do the proto-gay boys in Funny Boy and A Thousand Wings. There is no graphic sex in any of these three books (for gay Asian American fiction in which there is not only longing for male love but male-male sex there is Sex, Longing, and Not Belonging; Flipping; Searching for the Key, all of which I have reviewed—and none of which have the destruction of civil society as their backdrop as Letters to Montgomery Clift, Funny Boy, and A Thousand Wings do).

Also see my (2007) review of Alumit’s second book, Talking to the Moon.

published by epinions, 24 July 2002

©2002, 2016, Stephen O. Murray